Barry Sonnenfeld, A Life in Movies, Pt. 1

Barry Sonnenfeld–A Life in Movies

part 1

The Men in Black and Get Shorty director on how he wandered into film school, the filmmakers who’ve influenced his work, the dos & don’ts of comedy directing, and more

by Michael Gaughn

July 17, 2023

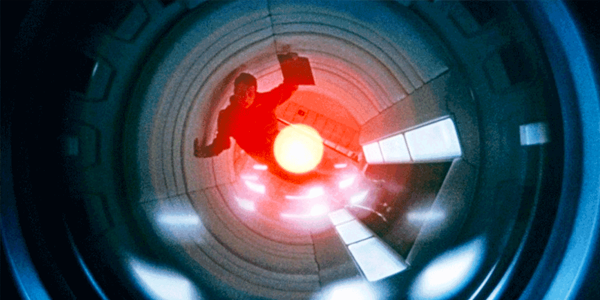

above | a very young Barry Sonnenfeld shooting Raising Arizona for the Coen brothers

Barry Sonnenfeld says he was never a movie fan growing up, and it’s clear from the interview that follows that he took a very non-traditional, almost reluctant, path to becoming a director. It’s not that he’s not keenly aware of or doesn’t appreciate movies—he put me on to Parasite a full year before it was released and his current favorite film is the hyper-stylized Indian production RRR. He just never felt the need to retreat into movies and movie lore the way wave after wave of filmmakers have since the 1970s.

Barry is actually a bit of a throwback. Until the emergence of the movie brats, movies tended to be made by people who had come from just about anywhere but the film industry. And they tended to be made by people who had already been out in the world and were able to draw on a depth and variety of experience that they were then able to convey through their work. It’s a considerable loss that we’re now saddled with directors—usually from the womblike world of the more affluent suburbs—whose experiences are at best limited and who only really know how to regurgitate the movies they’ve lost themselves in as an alternative to reality.

Given how much of his work is based in fantasy, and that his Men in Black helped pave the way for the current profusion of cheeky action-driven sci-fi fare, it’s easy to mistake Barry for one of the film-obsessed. So it’s surprising to read his autobiography, Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother, and realize how much his early experiences—especially his less than privileged and highly dysfunctional home life—have informed his films. (It’s hard not to see a link between his having had to disperse cockroach hordes every time he entered his parents’ kitchen and the alien infestation in Men in Black, and a surprising number of childhood memories permeate the third installment of that series.)

The interview below is basically a riff on his autobiography—not a repetition of its anecdotes but a kind of parallel commentary that further develops the story of how he came to be a hugely successful and influential director, highlights the movies and filmmakers that have inspired his work, and shows the insight and skill that led him to become a master of his craft.

The common perception is that film directors are all rabid film fans who’ll do whatever they have to to be able to make movies. But it’s clear from your book that you were never a big movie fan and that you kind of wandered into the industry.

That’s right. I didn’t grow up a movie buff the way the Coen brothers did, who shot their own Super 8 movies and did remakes of things like The Naked and the Dead. I ended up going to the NYU graduate film program only for lack of anything better to do. I really wanted to be a still photographer like Elliot Erwitt, Gary Winogrand, or Lee Friedlander, but my parents said they would pay for me to go to graduate film school—which turned out to be a lie. I ended up having to take out student loans and credit card debt at 18%. But I went to NYU and discovered that, along with my ability as a still photographer, I had some talent as a cinematographer. And those two things are very different since so much of movies is about moving the camera.

I will say that, in both my stills and my work as a cinematographer and then as a director, I’ve always gravitated to wide-angle lenses. I shot 95 percent of all my work in stills either with a 21mm or 35mm lens. And in my work as a cinematographer—especially with the Coens and Danny DeVito and some of the stuff I did as a director—my key lens was also a 21mm.

Wide-angle lenses force you to be closer to the action because they see so much. And by being closer, the audience subconsciously feels that the camera is near the actors. You feel a certain energy in the actor’s performance, especially with a wider lens closer—unlike, say, Michael Mann or Ridley and Tony Scott, who tend to use telephoto lenses.

Will Smith told me that when he did Enemy of the State with Tony Scott, he could never even see the camera. It was so far away with a 200mm or 300mm lens, he didn’t even know they were shooting. And there I am two feet away from him with a lens practically in his nostrils. So it’s a very different way of working.

Did Kubrick have any influence on your use of wide-angle in movies or is that more about the two of you being sympathetic in your approach to filmmaking?

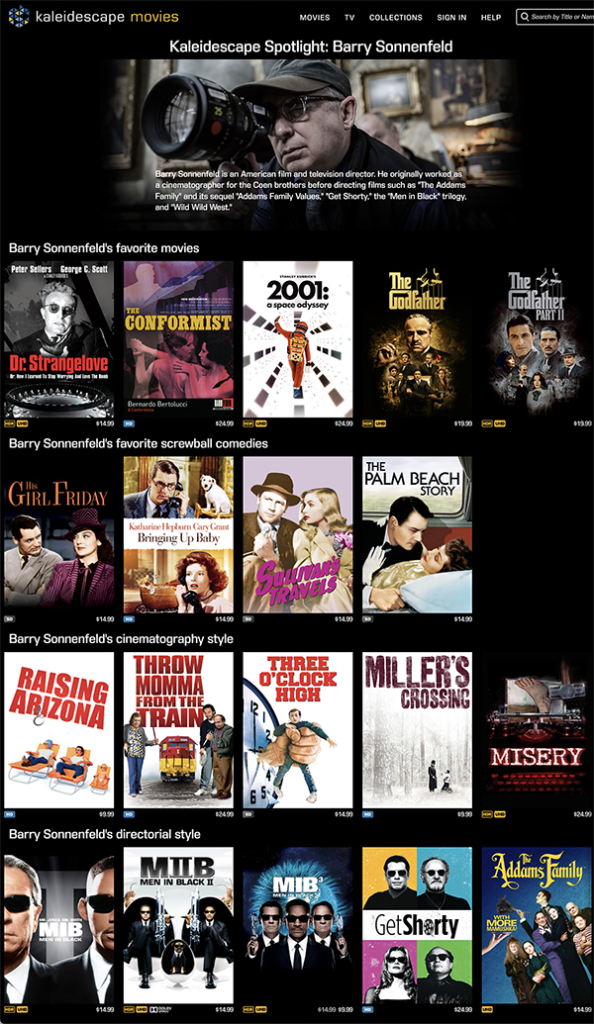

You know, Kubrick is my favorite director. My favorite movie is Dr. Strangelove. I also love 2001: A Space Odyssey. I hired Vincent D’Onofrio to be Edgar, the villain in the first Men in Black, in part because of his work in Full Metal Jacket.

What I love about Strangelove—which I think is also the best comedy ever—is everyone is playing the comedy as reality. No one’s trying to be funny. And because the reality is so surreal, stupid, and off the charts, that’s what makes it funny. It’s a perfect movie for expressing my kind of movie acting. The other thing Kubrick did so well is that he played

scenes out in masters, so you see action and reaction. You see Sterling Hayden and Peter Sellers next to each other while Hayden is talking about Purity of Essence and how he couldn’t get an erection after fluoridation of our water and all that; and in the same shot, you see Peter Sellers—it’s a raking two-shot—reacting.

The worst thing to do in a comedy is keep cutting around to tell people what’s funny. Let the reaction play within the scene. Let the audience decide what’s funny.

So, yes, Kubrick had a great influence on me, especially with how he designed the shots in Strangelove. Early on, there’s the scene with George C. Scott and Miss Foreign Affairs in a bedroom full of mirrors, and Scott is in the bathroom for half the scene off camera. There are no cuts—it all plays in this probably four-minute master—and it’s just thrilling how brilliant and daring it is not to have any cutaways to the other side of the conversation, not to cut to Scott in the bathroom. For me, that’s perfection.

That would seem to be a million miles away from somebody like Adam McKay, who has a very loose approach to directing comedy.

A movie I thought was very funny but is so not the way I make movies was his Talledega Nights. He is all about comedy improv. He writes stuff but then the cast just riffs and goes on forever. There’s the Baby Jesus dinner scene, where you can see that they’re shooting with two or three cameras. You see part of someone’s nose in this shot and someone’s ear over the shoulder in that, because in those kind of comedies, it’s not so much about the stylization or the visualization of the movie but funny dialogue.

It’s an equally valid way of doing it—just I couldn’t do it. I could not go on the set without a shot list, without a plan. I mean, I have seen directors rehearse a scene on set and then say to the DP, “So where do you think we should put the camera?” That’s crazy. It also allows

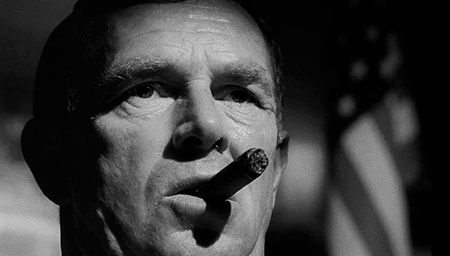

Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove

left | Tracy Reed and George C. Scott,

right | Peter Sellers and Sterling Hayden

making the comedy happen in the master shot—the delivery-room scene from Preston Sturges’ The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek

the actors to sit or stand wherever they feel like without telling them, “You’re going to come through the door here, you gonna . . .” It seems like such an inefficient way of spending your 12 hours a day on the set. You don’t want to spend any of that time figuring stuff out. You want to spend it filming—lighting, setting up shots, and acting.

Few directors—especially comedy directors—pace their movies on the set. They try to pace them in the cutting room instead. So they’re never saying to the actors, “Let’s just do one more where everyone talks faster” or “Do one more—pick up the cues between when he says this and you say that.” But then if you feel it’s too boring and you need to pace it up, the only way you can do that is through editing. And the more you edit, the more you cut around, unconsciously, the more the audience finds it less funny.

Again, what’s really funny are master shots, like Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant in the same frame [in Bringing Up Baby], with Cary Grant in her aunt’s bathrobe and Katharine Hepburn calling Grant “Mr. Bones,” which isn’t his name, while he’s trying get in a word edgewise with her aunt. And because it plays out in a master, it lets the audience find where the comedy is.

When I was the cameraman on When Harry Met Sally . . . and we shot the orgasm scene at Katz’s with Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal, in every preview we had, as big a laugh as Meg Ryan gets acting out her orgasm, when you see Billy doing nothing except staring at her, the laughs go from 40 dB to 60 dB—just because his reaction is the audience’s point of view.

You want to make the actors talk fast so you can stay on the master shot. Look at any Preston Sturges or Howard Hawks comedy—those actors are not even listening to what the other actors are saying. They’re coming right in with it. There’s no reaction. They’re just right on top of it. They’ve overlapping. It’s thrilling to watch. You don’t get directors controlling the pace on set these days. You have them trying to control it in the cutting room, which is wrong.

In Part 2, Barry talks about making Blood Simple with the Coens, his transition from cinematographer to director, and making The Addams Family and Get Shorty.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC