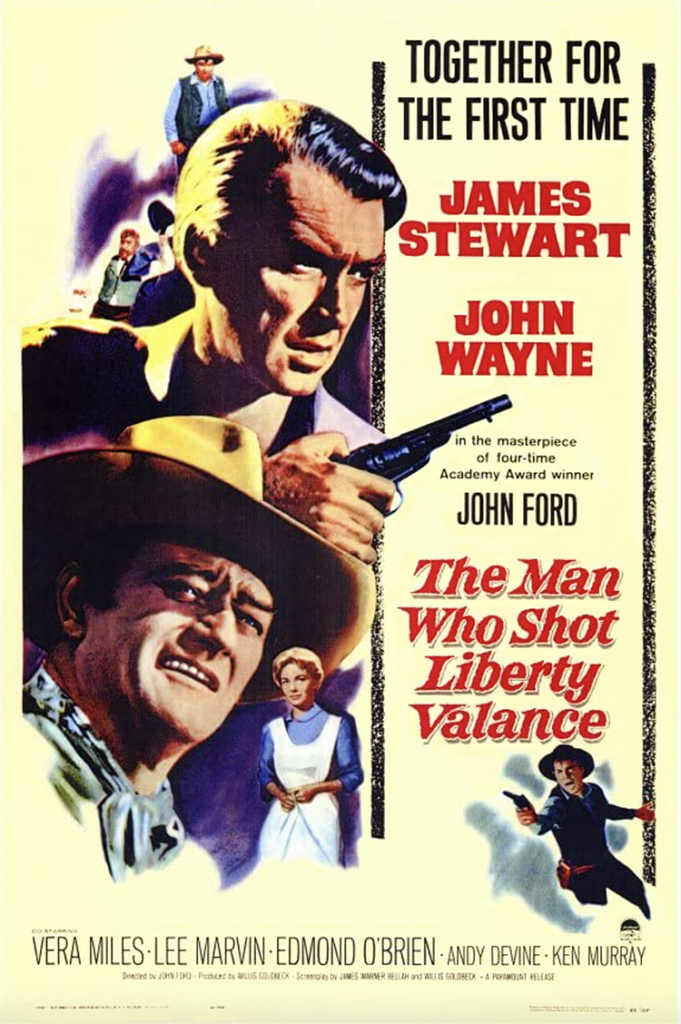

Review: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

also on Cineluxe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Even John Ford at his second best is better than almost any other filmmaker

by Michael Gaughn

February 7, 2023

Thomas Kuhn’s notion of paradigms doesn’t just apply to scientists but to practically anyone—including, or especially, movie directors. If goes something like this: No matter how brilliant you are, you tend to stay emotionally wedded to the concepts that made your career, which can make it difficult or impossible to grasp or accept any later innovations that challenge those core convictions.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is very-late-period John Ford, and the changes in shooting styles, production logistics, and public taste emerging in the early ‘60s all chip away at the film throughout—so relentlessly that it almost doesn’t survive the onslaught. What’s amazing—and distinguishes an artist from a dilettante—is that Ford uses all that disorientation to lay the groundwork for successors (and usurpers) like Leone and Peckinpah. (How much of that was conscious and how much intuitive is for another day.)

Rattling off Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, Strother Martin, and Woody Strode is like reading a roll call of actors who would soon become synonymous with the most prominent efforts to redefine the western. And their influence, and the influence of Valance, can be felt all the way to the present, thanks to hopeless film geeks like Tarantino.

Also influential was the film’s darkness, almost viciousness. Uncharacteristic of Ford, it emerged in some of his later films, especially The Searchers, and feels not unlike the sadistic bitterness of Hitchcock’s late films. In Searchers, Valance, and Cheyenne Autumn, you sense Ford tormented, challenging the convictions that defined his body of work while trying to ward off challenges from the larger culture, which was becoming similarly disenchanted with the defining myth of the American west.

Everything about the film feels slightly out of sync, most obviously with the performances. John Wayne specialized in playing flaming assholes, and as long as your worldview aligned with his, you saw his actions as righteous. But while it’s hard not to have ambiguous feelings about Wayne’s Ethan Edwards, his character here puts you very much in a yer-either-for-’im-or-ag’in’-‘im position that can make the film seem despairing, even nihilistic. And while Jimmy Stewart turns in a typically accomplished and untypically daring performance, the relentless bullying of the Wayne character makes Stewart look unnecessarily pathetic.

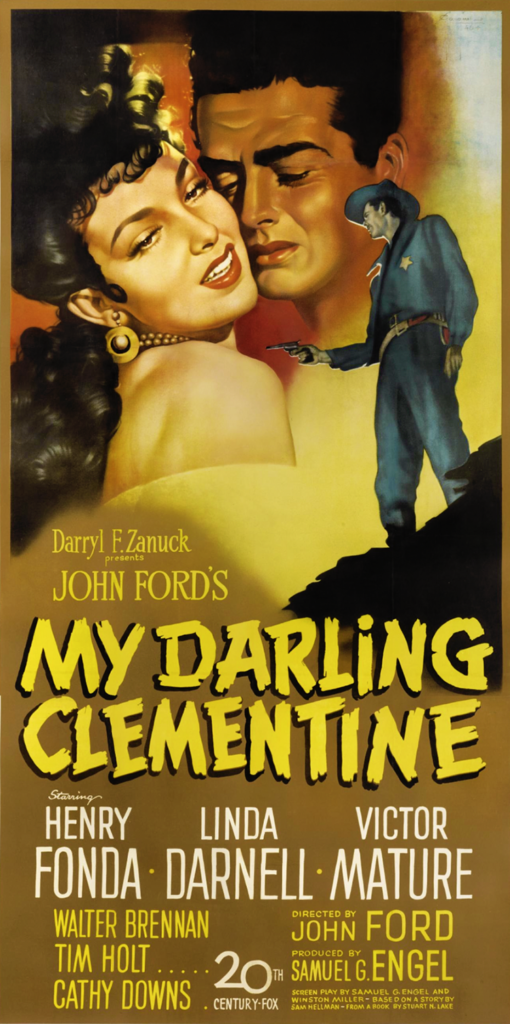

The visual style is similarly off, out of alignment with Ford’s defining aesthetic. Ford was a master visual stylist—possibly the greatest of the Studio Era—but he seems lost here. The sets and painted backdrops are all blatantly artificial, and the flat, high-contrast lighting makes Valence look like an episode of The Rifleman. We are many, many miles here from the depth and richness of How Green Was My Valley, The Long Voyage Home, Young Mr. Lincoln, My Darling Clementine, and Fort Apache. Having cut his teeth in the silent era, and with the classic studio techniques deep in his bones, Ford always had faith his production team would conjure up the film he wanted. But he had reached a point here where he could no longer bend the techniques to his will.

To be clear: I’m not damning Valance. It’s one of those very few films everyone should see at least once. It’s not Ford at the top of his form; but at his second best, like here, he was still breathing air at a strata the vast majority of filmmakers never come near. It’s fascinating and even enthralling to see him pushing back at forces he often doesn’t understand yet still sometimes finding a way to come out on top. And it’s, all else aside, a solid western—even if it looks more like a stage play or something shot in Edison’s Black Maria.

The transfer streaming on Prime might not be reference-quality but it’s a solid presentation without any jarring flaws. I realize those kinds of comments about streaming content are becoming redundant, but that’s a hugely promising sign. With the proliferation of wider bandwidth and the continual improvement of codecs, there’s every reason to think reference-quality releases of older films will be the norm on the major streaming services within just a couple years. Which raises the question: Why will we need anything other than streaming when that day finally arrives?

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC