Who Killed Film Noir?

also on Cineluxe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

The most powerful, nuanced, and incisive film genre America has ever created has been hounded into an early grave

by Michael Gaughn

November 27, 2020

From the World Monitor, November 23, 2020:

Film Noir, 76, died this past Saturday writhing on a traffic median in Bel Air, California, his final throes noted with amusement by motorists passing by. No one came to Mr. Noir’s aid, although a couple of prominent film directors did stop long enough to pick his pockets clean. At the same time, on the opposite coast, Mr. Noir could be seen lying on a sidewalk, bleeding profusely, outside a warehouse in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. He died surrounded by a crowd of people in their mid twenties to mid thirties. Oddly, all of them were dressed identically to the victim, and while they all bore large knives, none showed any evidence of blood. Again, not a single onlooker came to Mr. Noir’s assistance, although each member of the throng did take a little slice of him with them after he expired.

Film noir is dead. We, in our addiction to re-iteration and our blind political zeal, have managed to kill off what was probably the greatest—or at least arguably the most influential—American art form. But, before getting into all that, let me first define my terms.

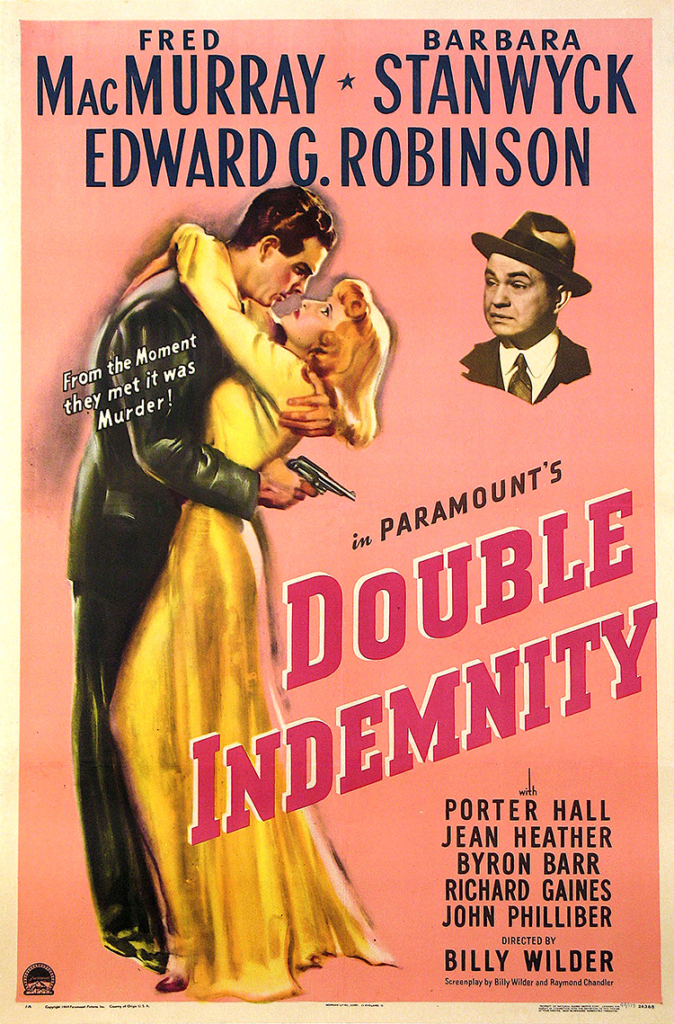

Let’s start with what film noir isn’t. While many people confuse crime movies with noir, very few fit under that umbrella. In fact, most crime films, as exuberant celebrations of unbridled strength and will, are the antithesis of noir.

The definition of noir can perhaps be summed up most succinctly via the title of a quintessential serie noire: You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up. Translated: Film noir is always and without exception a celebration—and a lament—of the chump. Its heroes always think they know the score, only to find that virtually everything around them is actively or blindly conspiring to do them in.

Noir is about total paranoia. It’s also about emasculation—more specifically, about the emasculation of white males. And, as such, it’s the antithesis of the myth of the American Dream. And, as such, it’s the thing that keeps us honest—real.

Or at least it did until the same regressive, Puritanical forces that have recently gutted so many other vital aspects of American culture got their hands on it. The rabid reactionaries, in their bratty petulance, seem to have an unerring instinct for taking down the things we all need to remain balanced, (relatively) sane, and whole. Of all the things we’ve lost over the past few years, the demise of noir may prove to be the thing we most greatly come to regret.

Noir could not be allowed to live, you see, because it was deemed irredeemably misogynistic. But let’s pause for a second to define misogyny. If misogyny hinges on always seeing women as inferior, servile, on denigrating them in an effort to assert the superiority of the male, then that tag can never be hung on film noir. The female characters in noir tend to be sharper—certainly more dominant—than the males—to a degree that tends to put the male protagonists literally to shame.

And it also needs to be said that the characters in noir, both male and female, tend to display far more shades of gender identity than the characters in any other film genre, past or present. That this isn’t done within the narrow, sterile lanes of the current rulebook makes noir’s take on gender more relevant, not less.

But what about that great bugaboo the femme fatale? The whole point of noir is that everything is trying to do in the male protagonist—close relations, colleagues, strangers, institutions, objects, environments—everything. So why would the female the lead feels most strongly drawn to be excluded? Wouldn’t it be logical that, given his desire to feel whole, but fearing the ferocious power of sexuality unbound, he would come to see her as his greatest threat? Again, to watch noir you have to understand that everything is a paranoid perception. There are no exceptions.

Given all that, explain to me how noir isn’t an evisceration of traditional notions of white male power, how it somehow empowers and emboldens the oppressor. And just so this whole exercise doesn’t come across as an expression of my own paranoia, let’s talk some specifics. Who perpetrated this crime? Who has noir’s blood on their hands?

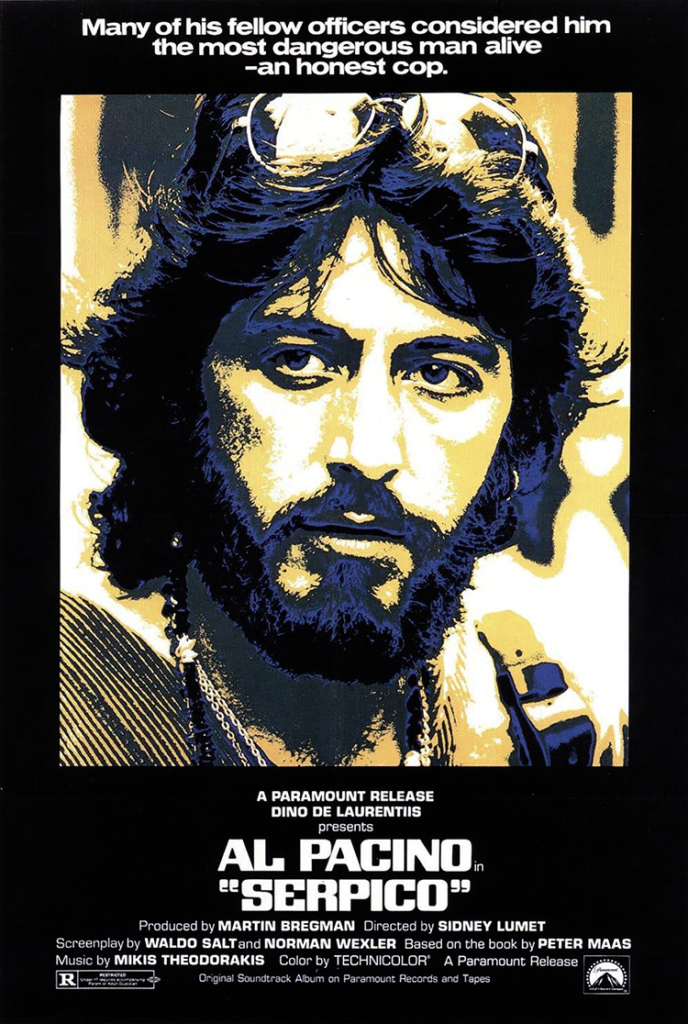

The list is long but I think the most telling example is the freshly recruited World War II bomber crew of hosts over at Turner Classic Movies. Carefully selected to address faddish ethnic and gender stereotypes but apparently not for their understanding of film, they espouse dogma, smile, then wait for someone off camera to throw them a treat rather than offer any unbiased insights into the movies they’re presenting.

Essentially, TCM has become a school for political re-education, looking to so rigidly rewrite history that it becomes impossible to see older films on their own terms but only by the current, borderline meaningless, standards. And given that film noir remains the most subversive of genres, it should come as no surprise that it’s the body of films they have most firmly fixed in their sights.

TCM guts noir by turning it into propaganda. The mannequin-like hosts will tell you all that really matters about noir is its female leads, who are all wonderfully strong, independent, and assertive—in other words, role models. The day anybody goes to noir for positive life lessons is the day the trumpet sounds, the moon turns to blood, and we break the Seventh Seal.

But it’s hard to say who are the guiltier criminals here—the commentators or the so-called creators, the latter largely a herd of film-school replicants safely skating atop genres they don’t understand because they’re too damned scared to look beneath the surface, cranking out bright, nasty objects without life or soul.

I would posit that the labyrinthine and woefully misguided rules about what can and can’t be presented, how what can be presented has to be presented, and who’s deemed acceptable to represent and present have made it impossible to create anything resembling true noir. (I originally wore “honest” noir, but what value would the genre have if it wasn’t inherently dishonest, the shabby, disreputable home of iconoclasts, tricksters, and other miscreants who no longer have a place in the contemporary world?) The only form that could possibly survive the current puerile gauntlet is faux noir—and who needs that?

We seem fated to a near future—and likely further—of makers and their Pavlovian subjects who believe embracing “dark” somehow wards off true darkness, little ornamental rituals of pain somehow inoculate them against true pain, and rigidly codifying and policing behavior can protect them from any and all transgressions—i.e., reality. Self-pitying masochism offers no basis for legitimate expression. Noir has nothing to offer a tribe that silly and shallow.

At a time when the paucity of new releases has led to more and more people being exposed to older films for the first time, it’s never been more important to approach classic movies with due respect for the way they were originally created and perceived. How anybody could look around at the fine mess we’ve made of current society and think we’ve advanced in any meaningful way, let alone in a way that would allow us to damn the past, would be laughable if it wan’t so grisly. No other film genre is as challenging or insightful as noir. Considering it with an open mind can provide a new, healthier perspective on the present. Approach it with blinkers on and you might as well watch a Teletubbies marathon instead.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

“The rabid reactionaries, in their bratty petulance, seem to have an unerring instinct for taking down the things we all need to remain balanced, (relatively) sane, and whole.”

“TCM has become a school for political

re-education, looking to so rigidly rewrite history that it becomes impossible to see older films on their own terms but only by the current, borderline meaningless, standards.”

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC