Review: The Purple Rose of Cairo

recent reviews

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

This deeply bittersweet look at the consequences of escapist culture resonates more strongly today than when it was first released

by Michael Gaughn

March 13, 2021

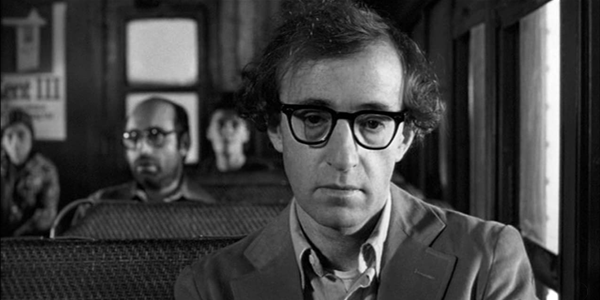

Of all of Woody Allen’s many films, The Purple Rose of Cairo deserves to be in, or near, the Top 5. I doubt anyone has ever treated the subject of mass-produced fantasies and their consequences as incisively. And Allen does it without turning it into the type of cold-blooded, too-clever-by-half intellectual exercise that tends to rule the roost today.

In an initial viewing, Purple Rose can seem lightweight, in a charming and quirky kind of way. It’s Allen’s most successful attempt to translate the style of his S.J. Perelman-type short pieces for The New Yorker to the screen. But while those pieces, hilarious as they often are, tend to be little more than a kind of absurdist riffing, here he manages to interweave a decent amount of earned emotion with the absurdity; and when he veers into sentimentality, it reinforces his critique of pop fantasies and comes with a bite.

While Mia Farrow gives what might be her best performance, it’s Jeff Daniels who walks away with the film. It’s hard to imagine the one-note Michael Keaton pulling off playing two similar yet very distinctly different roles, let alone looking like a Hollywood actor from the ‘30s. And yet Daniels aces it, also bringing a bland Midwestern quality to his portrayal that makes Gil Shepherd’s eventual betrayal of Farrow that much more affecting.

Without that last-mentioned turn, the film would have been little more than a very funny confection. But Allen’s movies, as he emerged from his mid period, began to display a maturity, a grounded and often troubling depth, he’s never gotten enough credit for. If he had opted for anything resembling a traditional happy ending, Purple Rose would have been little different from the fluff it both embraces and skewers. Shepherd’s all-too-human duplicity is a bracing jolt that throws the dangers—and irresponsibility—of the easy retreat into fantasy into context. Nobody can stop you from escaping into fantasy worlds—something the culture industry has shifted into hyper drive to encourage since the grim turn of the century—but it always comes at a hefty price.

And you have to wonder if the contemporary masses aren’t so thoroughly indoctrinated, so caught up in the endless, indulgent, self-congratulatory, self-referential, and insanely lucrative exercises in overgrown child’s play, for anything like this to even begin to resonate anymore, if Allen’s point isn’t utterly lost on a world that just wants to be left alone with its toys.

After landing that blow, though, Allen does cheat a little with an unfortunate shot of Shepherd looking wistfully out a plane window as he flies back to Hollywood from Farrow’s bleak corner of New Jersey. That moment seems to let Daniels’ character off the hook way too easily. It’s not that Allen shouldn’t have gone there but something more ambivalent would have rung truer.

I need to pause for a moment to acknowledge Danny Aiello’s performance. An actor all too often typecast, Allen plays off from that here, taking an archetypical abusive goon and making him, if not palatable, at last understandable. Consider the distance from Sylvester Stallone in a black leather jacket beating up old ladies on the subway in Bananas and you have an accurate gauge of just how much Allen grew as a filmmaker. And Aiello takes the opportunity and runs with it, without ever breaking a sweat.

Dianne Wiest deserves similar praise. If she hadn’t been able to bring depth to her portrayal of a roaming prostitute, Daniels-as-Tom Baxter’s sojourn in a bordello would have been little more than an extended cheap laugh. But she and Allen give her a basal dignity that keeps her and her fellow co-workers from becoming objects of ridicule.

And now we once again come to Gordon Willis. It would be impossible to decide which film represents his best work for Allen, but I would have to put Purple Rose really near or on par with Manhattan. He doesn’t really do anything bravura here, but it’s all strong. How he and Allen were able to take a closed-for-the-season amusement park in the autumn chill and turn it into a subtle metaphor for the film itself and for the torpor of America in the middle of the Depression remains both stunning and sublime.

As with A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, the cinematography holds up surprisingly well in Blu-ray-quality HD. Most of the subtlety is retained, only occasionally marred by excess noise and grain. Patches of bright light remain a problem, but not much can be done about that until the increasingly distant day when this film gets lifted up to 4K HDR.

The most egregious problem is the shots in the film-within-the-film that were radically enlarged on an optical printer. Allen obviously shot all of these as masters and then decided in editing that the other characters in the frame were too distracting. I don’t remember these images being this grainy and blobby when seen in a theater, but here they look like somebody spliced in some degraded VHS footage.

The weakest thing about Purple Rose is Dick Hyman’s score. It’s unfortunate Allen leaned so heavily on Hyman in his films, because, while he was a technically proficient musician, his work tended to be slick and soulless. Fortunately Allen’s material is strong enough to not be unduly weighed down by the seemingly arbitrary and often incongruous cues, but it’s a shame Allen couldn’t have cobbled together the entire soundtrack out of vintage music instead.

Many of Allen’s films are about characters who easily—and often, too easily—slip into fantasy worlds, and many of his protagonists are haunted by fantasy projections of the past. Key films like Annie Hall and Stardust Memories show Allen himself, thinly disguised behind fictional monikers, having a hard time, by his own admission, separating fiction from reality. His condition, which at one time was seen as an aberration, has since become desirable, is now accepted as the norm. While he frequently played that tenuous hold on reality for laughs, he never fully accepted it, and Purple Rose remains his most trenchant look into what has become the very heart of the culture.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC