also on Cineluxe

click on the image to enlarge

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

A way for non-Beatles fans and Fab Four newbies alike to get up to speed on the Disney+ documentary

by Mark Smotroff

December 12, 2021

You’ve likely heard about Peter Jackson’s remarkable documentary showing exclusively on Disney+ about the Beatles’ 1969 recording/film project, Get Back. It’s an extraordinary accomplishment that the Lord of the Rings director worked on for four years with the full support Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr as well as the families of the late George Harrison and John Lennon. Jackson’s documentary is revelatory. In many ways, it’s more than a documentary, containing many of the qualities of a great drama: A quest, conflicts, an urgent time limit, unexpected challenges, love interests, cliffhangers, etc.

Get Back is of course a dream for Beatles fans, many of whom have long been immersed in the back story—and the related mythology, which has evolved over the years. Fans have studied every outtake and alternate version of tracks from the sessions—which is all fine and good for myself and millions of hardcore Beatles fans around the world. We are arguably the world’s biggest insider club!

But as I watched this expansive three-part documentary, I pondered how the uninitiated might try to absorb its significance. Making sense of a deep dive like this, as great and innovative as it is, has to be intimidating for the casual fan and for anyone just discovering the Beatles’ music for the first time.

Contemplating this, I realized Get Back has much to offer anyone on either side of the Beatles fence. And thus the focus here is to provide some perspective to help everyone outside the club of Beatles fanatics—those of you who never got to go to a Beatlefest or even see the original 1970 version of director Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be film—appreciate Jackson’s documentary.

The Beatles conceived Get Back as both a recording and film project with the intention of bringing them back to their rock ‘n’ roll roots and a simpler production style of live in-the-moment recording. Consider this as opposed to the expansive and often experimental richly overdubbed and orchestrated productions they’d pursued from 1966 through 1968 on landmark albums like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Magical Mystery Tour, and The White Album.

The idea was to have the project lead up to some sort of live performance of the new music. This was significant because the Beatles had retired from touring in 1966 as their enormous stadium concerts were effectively a circus of out-of-control crowd mania, bad sound, and increasingly dangerous social challenges surrounding their performances, for the fans and band alike.

The results of this project were the Let It Be film—which had a short initial theatrical life and later home-media release on VHS and LaserDisc—and the corresponding soundtrack album. The film has often been scorned by many for its dark perspective. Released more or less simultaneously with the Beatles’ official breakup, it felt tied to that event even though it was recorded more than a year earlier (before Abbey Road). Yet, since it offers different footage and focus than this new version, it will remain a part of the Beatles’ legacy.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and as Jackson began his archeology-like research—reviewing more than 100 hours of audio and some 60 hours of film footage in the Beatles’ archives—he excavated a bigger story that had been buried along the way. The Get Back sessions weren’t all doom and gloom! Sure, the group was dealing with big problems on multiple fronts at the time, including poor communication, business mismanagement, solo side projects, family responsibilities, and general band-member exhaustion. But at the end of the day, they were still the Beatles, so they found the energy to create some timeless music out of these challenging sessions.

It’s precisely that ability to craft amazing music in the face of adversity that makes this film so powerful. Consider Get Back as a master class in the challenges and triumphs of a team creative process versus just a simple portrait of a band making an album and a possible TV special.

Indeed, one of the most fascinating elements in this program is that we get to see the Beatles writing music in the moment, effectively in real time. Watching them work together on an eventual No. 1 hit like “Get Back” from the ground up is magic. It’s a remarkable moment seeing Paul intently noodling on his bass guitar, exploring a new riff right in front of George and Ringo. Like a skilled chef, the riff is kneaded, seasoned, and baked into the song “Get Back” right before our eyes. That moment alone makes this documentary worth watching.

We don’t usually get to witness this process with composers. This was the only time the Beatles allowed outsiders like camera people and film producers into their sacred rehearsal and recording spaces for an extended period. In 1970, this sort of self-exposure was prescient. In 2021, we take it for granted that fans get intimate access to the backstage life of celebrities on videos and social media.

The look of Get Back is fascinating and ultimately wonderful for film that was shot in 16mm in 1969. I suspect some level of digital wizardry was employed to remove scratches, dust, and dirt. It looks fantastic all things considered—vivid, colorful, welcoming, and warm. Ultimately, this new presentation allows the viewer to forget about it even being a film, immersing you in the Beatles’ environment. You are very much a fly on the wall in this intimate warts ’n all portrait.

The documentary’s visual dreamscape is unusual in that there is no traditional off-screen narrator apart from occasional text captions that explain the backstory of a particular moment in time. Mostly, it’s actual dialogue of the Beatles and their associates that tells the story. Along the way, you’ll get some help from the documentary’s producers to clarify what’s going on. For example, there are small montages such as the opening sequence, which summarizes the early 1960s Beatlemania phenomenon, bringing the viewer up to date to January 1969 for these sessions and where the band stood at that time.

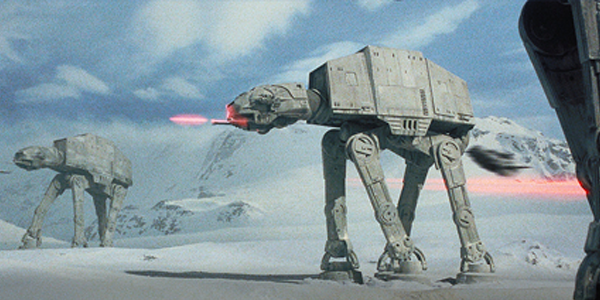

When the Beatles launch into Chuck Berry’s “Rock & Roll Music” (shown at right), Jackson visually puts that song into historical perspective, as it was the opening tune on their last tour. Brilliantly, he intercuts footage of the 1966 Beatles performing on stage in Japan juxtaposed with the 1969 session in a way that is both informative and impactful.

For Get Back, the Beatles had committed to a high-pressure, high-stakes creative process driven by an unrelenting live-performance deadline. Jackson’s use of a calendar as a vehicle for telling the day-by-day story is a super-effective but simple technique to help us keep focused on the group’s increasingly tight timeline.

But mostly, there is the bountiful music-making magic. Watching McCartney map out “Let It Be,” “The Long and Winding Road,” and “I’ve Got A Feeling” for the band is a wonder, as is watching George Harrison break out his song “For You Blue” in an early acoustic state before it had been shaped into the swingin’ blues romp it became on the album.

You’ll also get to see the Beatles considering songs they didn’t finish until years later. Many of them showed up on solo records by John, Paul, and George into the early 1970s, including McCartney’s future smash hit “Another Day” and “Back Seat of My Car” (the epic closer to his 1971 Ram album). George Harrison’s “All Things Must Pass” is tried out more than a year before it became the title for his first solo album. And Lennon’s “Give Me Some Truth” and “Child of Nature”—an early version of “Jealous Guy” —debut here two years before they appeared on Imagine.

Some tracks that didn’t make the final cut are explored, giving us a sneak peek at early renditions of songs from Abbey Road. These include Harrison’s magnificent pop-standard-to-be “Something,” Ringo’s whimsical “Octopus’s Garden,” Lennon’s proto-metal masterpiece “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” along with “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam,” as well as McCartney’s jaunty “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and poignant “Golden Slumbers.”

The first episode is the most challenging in the whole series to watch but is also the most enlightening. Here we see the Beatles coping with the crushing project timetable they had agreed to while facing the harsh film-studio environment they were working in, and all the challenges that came with it. One significant stylistic difference between Jackson’s Get Back and Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be is that we get to see just how enormous the Twickenham studio was. For all these decades, Beatles fans have read about its scope and how cold it was there in January but now you can almost feel how massive and chilly it was. In the 1970 film, most of the scenes are zoomed in on the band so you never get the feeling of the massive space.

That ginormous studio becomes a trigger for revealing underlying bigger problems the band was having, exposing creative and communication blocks. The new film is very transparent in that sense, putting all the cards on the table.

Over the years, I’ve often read about how the Beatles’ productivity escalated as soon as they got away from the film studio and into their own recording space, which was just being finished. But now we get to experience that change along with them. The whole vibe of the band transforms, almost like night and day. And when they bring in keyboardist Billy Preston to round out the sound, their creative energy pumps up dramatically. As the Beatles reconcile their disagreements and reconvene in their new studio, the attitude change is palpable. The sonic texture of the music changes so suddenly that we hear that unmistakable classic Beatles studio sound emerging more clearly.

Dispelling mythology is also important throughout the documentary, so scenes of Yoko Ono and Linda McCartney happily chatting go a long way to counter the notion that there was distance between the members’ families. McCartney himself is openly supportive of John and Yoko, again counter to much negative mythology that an alarming amount of Beatles fans still believe that Yoko broke up the Beatles. Heck, there are some amazing improvisational jams featuring Paul with John and Yoko, pulling feedback from his bass and other sonic textures. They clearly got along just fine. Kudos to Jackson for allowing the Beatles to set the record straight in their own words for the sake of historical accuracy.

Back to the creative process, it’s important to consider the Beatles’ consummate musicianship. Take note of how loose they sound just a couple days before their concert on the roof of Apple Records. The transformation is remarkable and is a testament to the group’s creative genius and skills. It all came together on those handful of songs they performed live that day. And the next day, they finished the others more or less the way we hear them on the final album (save for Phil Spector’s orchestral production additions).

And . . . if I might gush with Beatle-envy a bit—ohhhh, to have been one of those people who worked in downtown London during the concert, especially those who got up on the roof to actually see the event. The Beatles’ rooftop concert was arguably one of the first rebel concert experiences put on by a major artistic force. This was nearly 20 years before U2 took the concept to another level with their massive “Save The Yuppies” free concert in downtown San Francisco in 1987 (shown at right), which brought the city to a standstill.

If seeing the full rooftop concert complete wasn’t enough, Jackson includes footage of the band and their families jammed into the recording-studio sound booth to hear the playback of the live show for the first time. It’s just magical watching everyone’s reactions as they realize the Beatles nailed something special that day. Witnessing this creative process by one of the most influential forces in music history makes Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary an essential study for anyone interested in music.

Mark Smotroff is a freelance writer and avid music collector who has worked for many years in marketing communications for the consumer electronics, pro audio, and video games industries. He is also a musician/composer whose songs have been used in TV shows such as Smallville and Men in Trees, as well as films and documentaries. Mark’s most recent music project is a concept album/rock opera, for which he is slowly whittling away at “The Book.”

Dennis Burger looks into the controversy over the image processing and sound mixing in Peter Jackson’s documentary and offers up his conclusions

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC