also on Cineluxe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

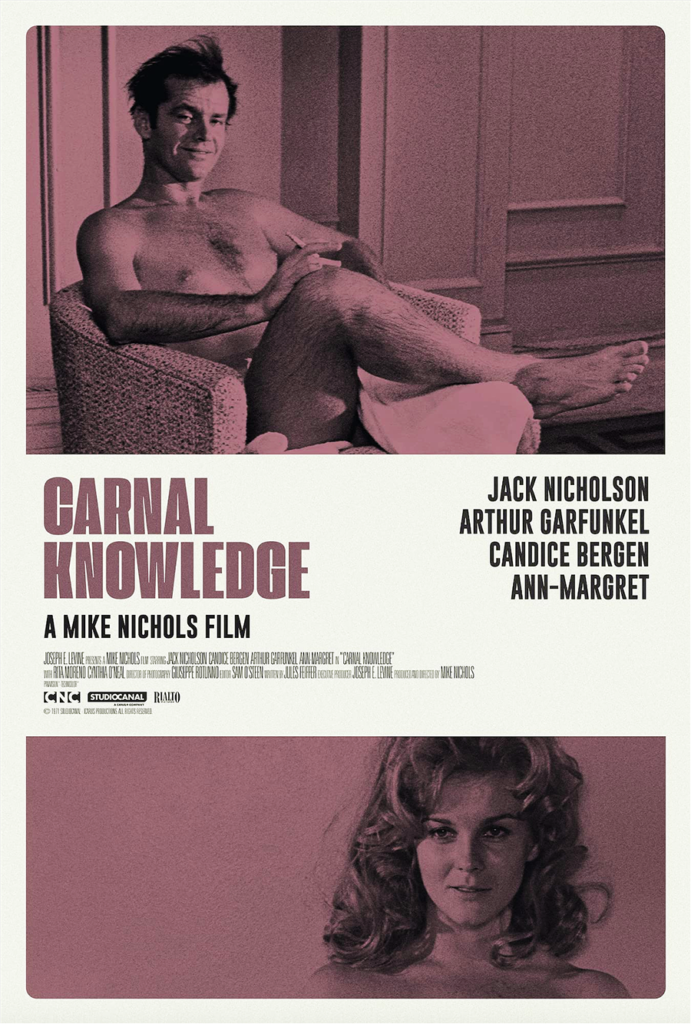

Its deceptively small scale and stripped-down style have led to this still vibrant Mike Nichols’ satire on fractured mores never getting the recognition it deserves

by Michael Gaughn

April 20, 2023

Not having seen Carnal Knowledge in a while, and not exactly sure what my impression was of it the last time around, this recent viewing was something of a revelation. Mike Nichols’ deeply quirky, deeply sardonic big-name, big-budget miniature is one of those one-off, completely sui generis films that pop up from time to time that really shouldn’t work yet somehow manage to coalesce and succeed. For something so deeply rooted in its extremely unstable era, it holds together amazingly well and seems even more expressive and potent now, probably both because it taps into timeless constants of behavior and is such a spot-on portrait of that time.

Nichols was once considered a genius filmmaker, but that was mainly hype. He’s now known, when he’s known at all, as the guy who did The Graduate—a film, like Breakfast at Tiffany’s, that recent generations have willfully misconstrued to help bolster and justify their preoccupations and prejudices. His movie career began with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, an overly long adaptation of Albee’s play made watchable by unexpectedly powerful performances from Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Then came The Graduate, a bit of a mess of a movie that awkwardly tossed together attempts at late ’60s social consciousness with European art-film pretentiousness and a lot of TV comedy schtick, thanks mainly to Buck Henry. Again, it was the performances that made it work. Next was Catch-22, which was—from conception to production to final release—a mess on a monumentally larger scale. (Sensing an opportunity, Robert Altman created M*A*S*H as a pared-down, knowing, and kind of nasty retort to Nichols’ disaster. Altman was then able to use the huge box-office generated by his low-budget farce as the springboard for his career.)

While this is a somewhat simplistic tack, it’s hard not to see Carnal Knowledge as a reaction—possibly traumatic—to the overweening nightmare of Catch-22. Instead of a cast of thousands, the ensemble of players is so small it fits on two title cards with plenty of room to spare. Instead of staging a vast, coffer-draining military operation, the action plays out, in highly stylized form, on a series of modest, even spare, sets. Instead of epic spectacle, there’s people, just a few, and most often shown in medium shot or closeup, sometimes speaking directly to the camera.

And, as with Woolf and The Graduate, Knowledge is very much an actors’ showcase. It’s not that Nichols is shy about deploying his filmic technique or afraid to experiment stylistically, but for the only time in his career, that technique is a completely organic extension of the material, expressive and reinforcing and consistent.

Jack Nicholson’s performance is from start-to-finish astonishing, running the gamut from charming to insecure to cooly detached to terrifying—probably his best work. Anyone who hasn’t seen him in Knowledge has only been exposed to a fraction of what he’s capable of. Still a relative newcomer who’d only recently gotten his first serious attention in Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces, you can sense Nicholson relishing the chance to finally work with a sophisticated script and a first-rank director.

What I’m going to write next might be even more astonishing, because the rest of the ensemble—Art Garfunkel, Candice Bergen, and Ann-Margret—none of them blessed with acting chops within spitting distance of Nicholson’s—all rise to the occasion, turning in nuanced, daring, exceptional performances. None of them had done work this good before; none would ever do anything better.

It’s too easy to lean on the saw that what’s best about the best films often has more to do with the cinematographer than the director, even though that’s often true. The meaning of “best” is so multivalent and slippery, and so many factors can contribute to what does and doesn’t work in a movie, that it’s rarely useful to ride that thought too hard. (And, to utter the ultimate heresy, producers probably have more to do with a film’s creative success than either the director or the cinematographer—especially since the turn of the millennium.)

That said, Giuseppe Rotunno’s considered but spellbinding photography undeniably gives Carnal Knowledge a consistency, solidity, mordancy, wit, and grace it would have lacked otherwise. It and the acting are equally stunning, but Rotunno’s work is what holds the production together, what makes it sing.

The late ’60s and early ’70s were not kind to cinematography. Film stocks tended to be too slow to keep up with what filmmakers were trying to achieve, and post production was a shambles in the wake of the collapse of the studio system, so nobody seemed to know how to properly put a film together anymore. And yet Rotunno’s work here—a European working in the wreckage of the old Hollywood—is brilliant and unassailable. Any contemporary director could glean volumes by going back to Knowledge for a refresher course in the rudiments of post-Studio Era film grammar. Rotunno shows how to be experimental without being pretentious, theatrical without looking stagebound, virtuosic without being smart-ass.

But some of the credit also goes to production designer Dick Sylbert, his sister-in-law Anthea as costume designer, and editor Sam O’Steen—the same team that had worked on Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby three years earlier and would work on Chinatown three years on, able to achieve the craftsmanship of Paramount in its heyday at a time when that kind of resourcefulness and finesse had fallen out of favor.

The elements for the transfer streaming on Prime are a little beat up but not unacceptably so, nothing that will take you out of the experience once you get beyond the random scratches and dirt during the red-on-black opening credits. All in all, this is a damn fine presentation that’s remarkably true to the film. The color levels seem accurate, blacks—which are crucial to the look—are solid and deep, and whites are similarly solid, only exhibiting noise in some tiles on a bathroom wall during a tracking shot.

Since Knowledge isn’t considered a “big” movie, who knows if it will ever receive the restoration or 4K bump-up it more than deserves. But there are classics of the marketing-driven, “I loved that when I was a kid” kind, and then there are true classics, as in legitimate works of cinematic art. Carnal Knowledge falls solidly in the latter camp and ought to be on the short list of films worth seeking out for anyone who hasn’t yet encountered it.

The soundtrack, like the visuals, is deceptively simple—clean and dynamic and surprisingly satisfying for mono. Yes, mono.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | A damn fine presentation that’s remarkably true to the film. The color levels seem accurate, blacks—which are crucial to the look—are solid and deep, and whites are similarly solid, only exhibiting noise in some tiles on a bathroom wall during a tracking shot.

SOUND | The soundtrack is deceptively simple—clean and dynamic and surprisingly satisfying for mono

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC