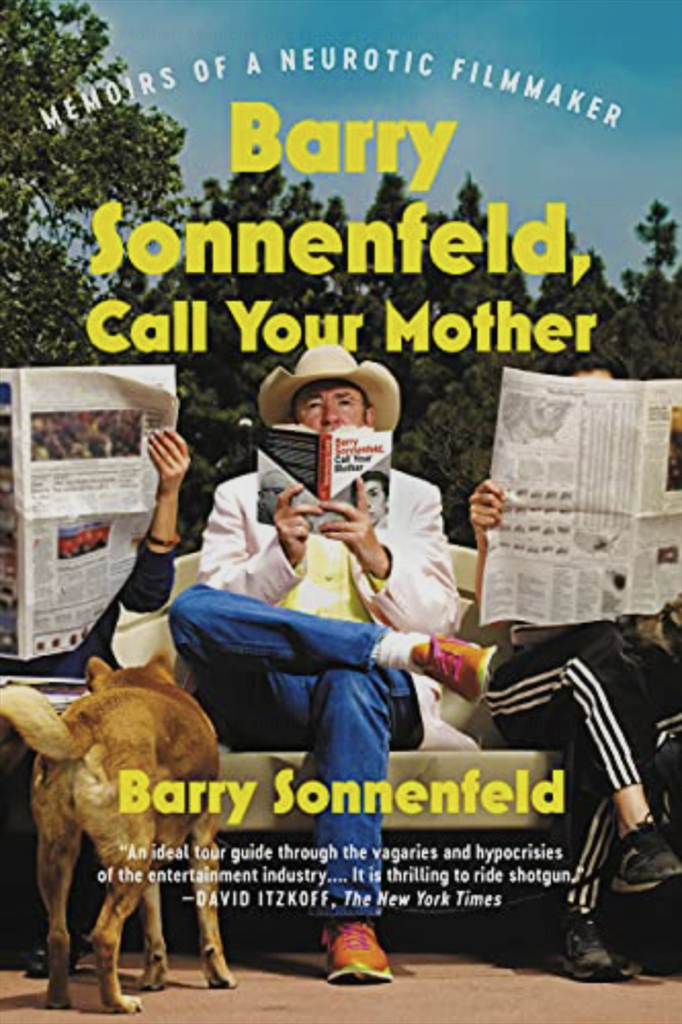

Barry Sonnenfeld–A Life in Movies, Pt. 3

Barry Sonnenfeld–A Life in Movies

part 3

The series concludes with the legendary comedy director sharing his thoughts on the art of the movies and what it takes to master the craft

by Michael Gaughn

August 3, 2023

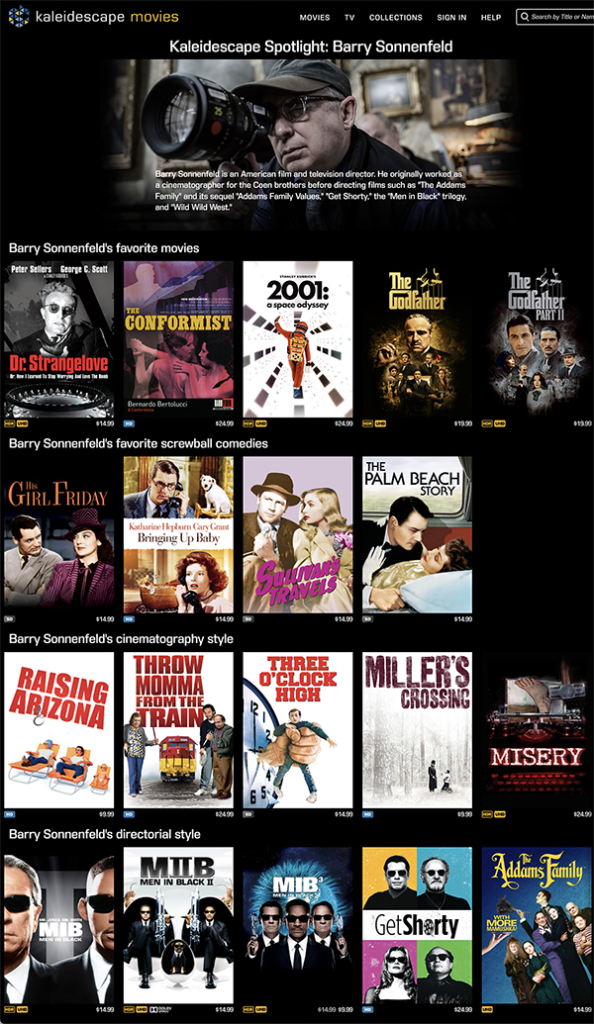

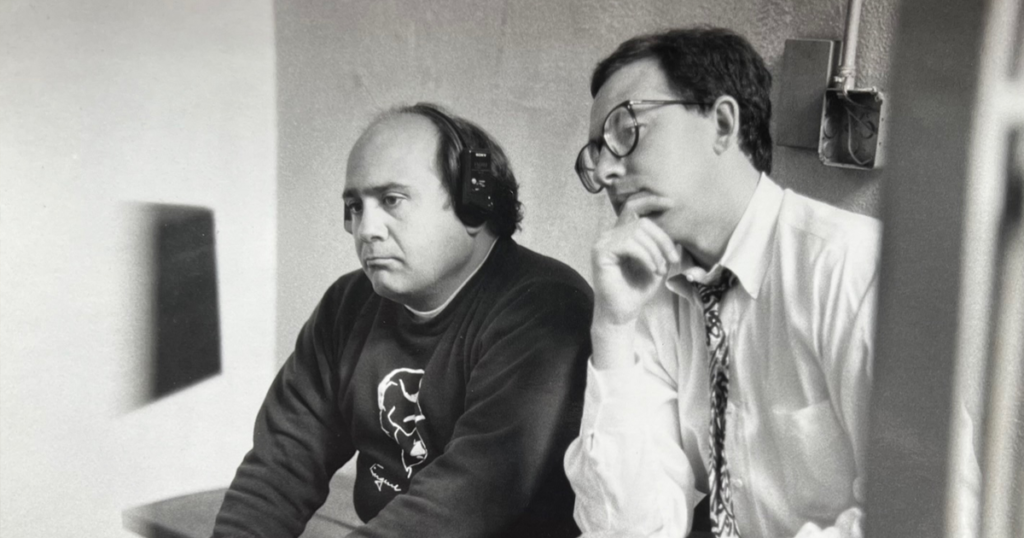

above | Barry Sonnenfeld setting up a shot on the set of Netflix’ A Series of Unfortunate Events

related reviews

Julie Christie in Heaven Can Wait (1978)

While Parts 1 and 2 did touch on shooting and directing, this final installment focuses mainly on Barry Sonnenfeld’s unique take on the art and craft of making films. Because he’s known mainly for comedies, critics and commentators have never given him all the credit he deserves. But Barry’s influence on the cinematography for and direction of the comedy genre has been tremendous, helping to pivot it away from the static, stagebound approach that has dominated the form ever since the inception of film to a more dynamic, adventurous style that helps put the camera on an equal footing with the actors.

And, just to tidy things up, you’ll find some digressions here on film school, his favorite cinematographer, and tangling with a troublesome future President.

Your work has always had a very distinctive style, even when you were shooting for others, but it never seemed to just be style for style’s sake.

What I think I brought to a lot of the movies I shot in the ‘80s and that I directed from the ‘90s on was that I used the camera as a storytelling device and not just a recording device. Many directors set up the camera to just record the story but they don’t use lens selection or camera movement as part of the story tone. And what I did, with Throw Momma from the Train and Raising Arizona—I did it also with Three O’Clock High, which I actually shot but was credited as the lighting consultant because I wasn’t in the west coast union—was make the camera part of the storytelling, make it almost a character in the movie.

And that was at its most insane with both Raising Arizona and Throw Momma—well, even in Blood Simple, when the camera tracks along the bar, booms up because there’s a drunk in the way, booms back down and continues on. I was at the New York Film Festival when Blood Simple was shown and the fact that a shot could get a laugh—there’s no dialogue, there’s nothing—that’s thrilling to me. As a cameraman, to be able to create comedy just through a camera move is perfection.

And you said the Coens originally cut that out of the film.

I went to their editing room one morning, and the shot was out. And I said, “Why did you cut it out?” and Ethan said, “I don’t know, it seemed a little self-conscious.” And I said, “Have you seen the rest of the movie? Why just pick on that shot?”

You know, there are shots where the camera’s mounted on the same rig with Fran [McDormand], and you think she’s in Marty’s bar and then the camera and her tilt 90 degrees, and we find out we’re—we put a pillow and sheets on the floor, so she falls through space, and now is in her bedroom as it transitions. So there was nothing but self-conscious film-school stuff in that movie.

Even today, most comedies are shot pretty conservatively. The Judd Apatow/Adam McKay camp and its offshoots are mainly about getting straight recordings of the performances.

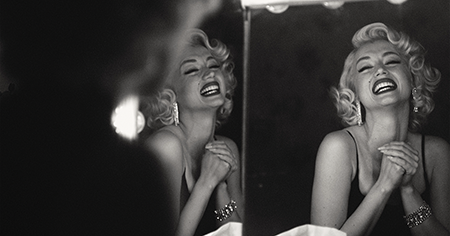

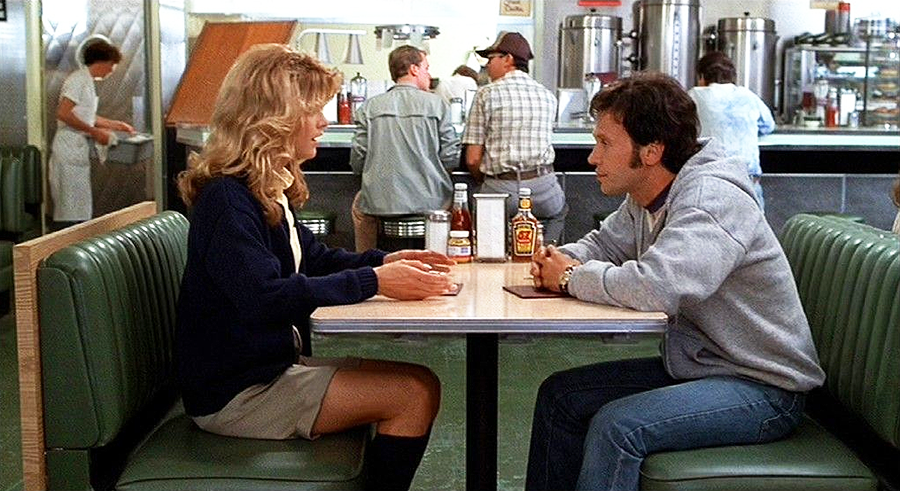

There aren’t that many cinematographers who know how to stylize comedies. I mean, Bill Fraker, one of the most famous cinematographers there are, was a brilliant comedy DP. He shot Heaven Can Wait for Warren Beatty; he shot 1941 for Spielberg—not a particularly great movie but a beautiful comedy. Fraker didn’t use a camera to tell the story, but he was a great lighter.

Where does Gordon Willis fit into all this, since he shot all those comedies for Woody Allen? I know that when Diane Keaton found out Willis was going to shoot Annie Hall, it was like, “Why did you hire him?” because she couldn’t imagine him doing a comedy.

It’s so funny you say that because Gordon Willis was by far my favorite cinematographer. And his stuff looks nothing like mine. But it’s so beautifully, beautifully lit and photographed. And you’re right, Gordon Willis is another guy who knew how to shoot comedies. He didn’t like to move the camera much at all.

I was just going to say that you’re never aware of when he’s moving it.

Right. But I was honored when I was being interviewed by a reporter from Variety about two years ago and she told me she had asked Gordon Willis who his favorite cinematographer was working in his era, and he said it was me. And that is thrilling to me because we have such different styles. The closest, I would say is, Miller’s Crossing, which could have looked like Gordon shot it—very contrasty, the strong sidelight, stuff like that.

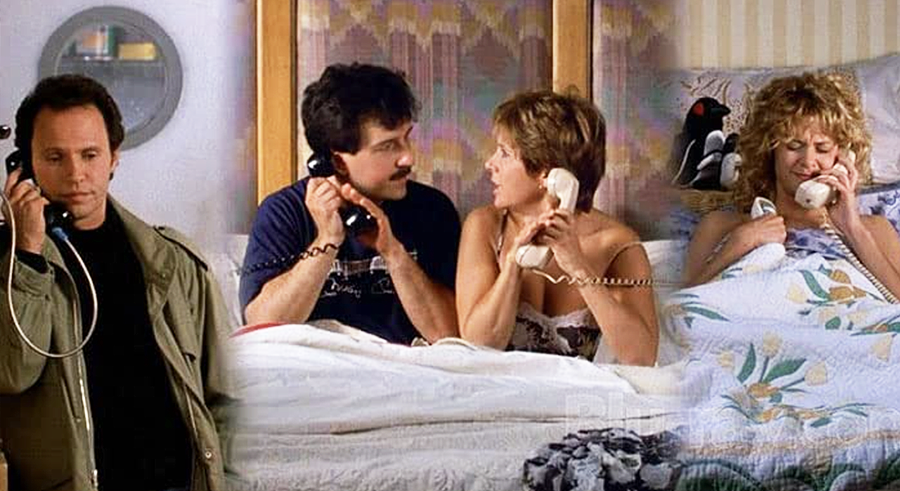

virtuoso comedy: Gordon Willis’s four-character long-take tracking shot through Soho in Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979)

aliens in broad daylight on the streets of New York—Men in Black (1997)

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Do you think of yourself as a New York filmmaker? Until I read your book, I never really thought of you that way. You’re usually associated with Hollywood-type films but everything about you is New York.

That’s really good. I never thought of it that way either but, yes, I do consider myself a New York filmmaker. I worked very hard to get Men in Black rewritten so it took place in New York. When I came on, it was in Las Vegas and Washington, DC, and Lawrence, Kansas. And I kept saying, “If there are aliens, they’re in New York.” Because in New York, you can pass without any disguise, you know.

I recently talked to somebody who entered the NYU graduate film program the year before you did, and he said his experiences were very similar to yours, that he had to deal with a lot of bitter faculty members with one credit to their name and was fighting the faculty and administration all the way through just to get anything decent done.

Things might have changed, but when I was in the program, most of the teachers—who were actually good—were all kind of disgruntled and were no longer in the industry because they, for various reasons, couldn’t hack it. But the truth is none of them could teach anything until we started to shoot stuff. Sitting there watching The Sound of Music in directing class didn’t really help me, you know.

When you started to shoot, that’s when you realized, “O, that’s why you can’t shoot one over-the-shoulder with a 21mm lens and do the reverse with a 75. It looks wrong.” “O, that’s why you need coverage.” “O, I’m shooting everything too tight and I don’t know where I am.” By doing, that’s where you learn. And that’s also where the teachers can help you once they’re sitting with you, in the editing room or whatever. But until then, waste of time, waste of money—just insanely expensive.

Film was so expensive, we had to design all the shots ahead of time. You couldn’t just show up and shoot endless masters and then do an over-the-shoulder of the whole scene. So we always were thinking as we were shooting, “How are we going to edit this?” So, if I was shooting a master, I would shoot the first 20 seconds of it and say, “OK, guys, now we’ll go to the last half of the page where you say, ‘I hate you,’ and leave,” because I knew that the whole middle, I would never be in that master. I’ve got to be tighter because of the emotion of the scene, or whatever.

Now that everyone shoots video, what do they do when they go to film school? Does the school give you a 16-gig SD card on the camera and say, “And you’re not allowed to buy your own SD cards. You can only use these 30 minutes”? I think it would create a different theory of how these students learn to make movies.

The other thing that’s changed is everybody on the planet seems to have filmmaking in their DNA now. Everybody knows how to make a movie. So what are you going to film school for? They all know how to shoot, they all know how to cut, and they know all the ins and outs of the industry.

That’s right. When we were going to film school, you couldn’t cut unless you were cutting with either a Moviola or a Steenbeck, which you had to rent, which meant you would rent it with two other students and work it 24 hours a day. Now you can cut anything you want on your Mac. You can shoot on an iPhone, which looks fantastic. And you can stabilize and move the camera through space, and there are gimbals and drones, and there’s LCD lighting—all these things that are so much easier.

You look at all those black & white movies, like Casablanca or His Girl Friday. They shot them with lenses that opened up to like f/4.5, and the ASA was probably 25 or 32. Since green and red look the same in black & white—gray—you couldn’t use color to separate people. You had to do it with lighting. And they shot them at most in like 20 or 30 days. It’s just amazing. And there was very little coverage. Things played out in master, and when you went in for coverage, you popped in. You didn’t change angles so much.

I wouldn’t go to film school now. You don’t need it for cameras, you don’t need it for editing, you can find other friends that want to act the same way we did. So I don’t know why anyone would go there.

This is neither here nor there, but did you actually boot Donald Trump from a Macy’s commercial?

Yeah. We did this big Technocrane shot that starts on all these people who had a branding thing at Macy’s—Martha Stewart, Emeril, Queen Latifah, Usher—we pulled back, back, back—and across to the other side of Macy’s—we built a Macy’s lobby at Steiner Studios in Brooklyn—there’s Donald Trump and three little kids at another table, like at the children’s table. And Trump says, “How did I end up here?” So we did that in the master. And now I was going to go in for a tighter shot of Trump. And he said, “You’re not shooting me from that side. That’s my bad side.” I said, “Well, I have to. I can’t shoot from the other side. It won’t cut.” He went, “Find another angle or I’m leaving.” And I said, “OK, see you. Thanks for coming.” He said, “You’re letting Donald Trump leave without getting a closeup?” And I said, “Yeah, it’ll be fine. You don’t want me to shoot from here, and I can’t shoot from where you want me to, so we’re good. It’s going to be great. Go home.” He said, “I’m leaving.” I said, “Yeah, you’re leaving. Goodbye.” So I went to do a two-shot of Martha Stewart and Queen Latifah, and everyone was a little freaked out—you know, the clients and the agency—because I let Donald Trump leave without his closeup. I’m setting up the shot, and there’s a tap on my shoulder, and Trump says, “Alright, you can shoot me on my bad side.” I said, “We’ve moved on, Don. Go home. We’re done. We don’t need you anymore.”

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC