How the best sitcom ever helped pave the way for many of our current cultural ills

by Michael Gaughn

AT ITS HEIGHT, The Dick Van Dyke Show was seen by more than 17 million viewers a week. The most popular sitcom of this past year, Young Sheldon, averaged just over 9 million viewers. There were 52,600,000 TV households in 1963; there are more than twice that now. Roughly translated, about 33% of the people watching TV in 1963 tuned in to the Van Dyke show, while around 13% of viewers today watch Young Sheldon. (I admit I’ve thrown enough apples and oranges together here to make a fruit salad but

related feature

Laura channels Jackie K. in “Coast-to-Coast Big Mouth”

also on cineluxe

the basic proportions are accurate enough.) And the programming on the only three networks available then added up to a tiny fraction of what virtually any TV viewer can access now.

In an age of rampant tribalism and the acute atomization of media, it’s easy to forget how dominant and influential a single TV series could be—especially when that series didn’t resemble anything else that had been on television and seemed like a harbinger of the medium’s future. There had been plenty of domestic comedies before Van Dyke but those husbands and wives were neither young or old but tended to exist in an ageless realm of staid maturity. And everyone tended to live in a non-specific middle-American everywhere. You knew the husbands had jobs but you rarely, if ever, saw them at work. The level of sophistication was decidedly low—everybody seemed to eat meat and potatoes, and if they went out at all, it was to the movies. Knowing references to current culture were taboo, considered likely to alienate the lowest common denominator.

Rob and Laura Petrie were young and hip-enough suburbanites living in the very real New Rochelle, NY with Rob taking the train or driving to his job in midtown Manhattan where he was the head writer of a comedy/variety show viewers readily identified with similar shows hosted by Sid Caesar, Red Skelton, and Milton Berle. The series was peppered with spot-on nods to Leonard Bernstein, bebop, Roger Corman films, Lenny Bruce-type comedians, Tennessee Williams, late-night talk shows, Ingmar Bergman, Albert Schweitzer, comedy albums, Off Off Broadway, underground film, and even the early days of audiophilia.

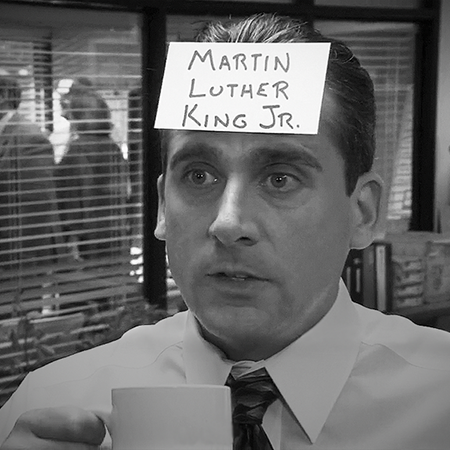

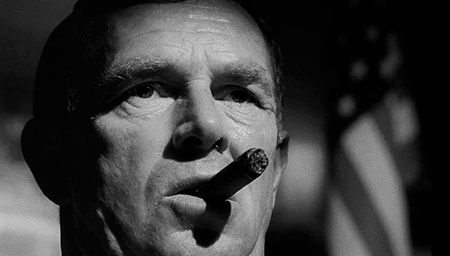

And at a time when nothing on TV was overtly political and definitely not specific, the Van Dyke show exhibited an obvious fascination with the Kennedy administration. In “Bank Book 6565696,” Rob yearns for a XKG-JFK-400 roadster. In “The Sam Pomerantz Scandals,” comedian Danny Brewster does a lengthy JFK impersonation. And Laura looks like a Jackie Kennedy clone when she goes to beg mercy from Alan Brady in “Coast-to-Coast Big Mouth.”

But it went deeper than that. The money for the pilot for the show that would become The Dick Van Dyke Show was put up by Peter Lawford—a has-been actor whose only fame at the time came from having married into the Kennedy fold. But Lawford was just the beard—the funds actually came from the Kennedys, and series creator Carl Reiner had to send his script to family head Joseph Kennedy for approval before the money could be released.

The series and the administration seemed fated to be intertwined. The first episode was shot on the day of Kennedy’s inauguration; and even though everyone on the show was in shock from the President’s assassination, Reiner decided to go ahead with filming “Happy Birthday and Too Many More,” just without the usual live audience. It’s likely coincidental, but the quality of the series, which crested during the 1963 season, fell off after the end of the Kennedy administration, as if it had lost its lifeline.

I don’t think it’s too bold to say that Reiner deliberately crafted the Van Dyke show to be a definitive expression of the late ‘50s/early ’60s Liberal agenda. Episodes like “That’s My Boy???,” “A Show of Hands,” and “A Vigilante Ripped My Sport Coat” are direct expressions of the movement—again, something new for series TV, where any kind of advocacy was strictly forbidden. Reiner only became overt with his leanings once the show’s popularity was established but that worldview, and those politics, were baked into Van Dyke from the beginning and permeated it so completely that there’s barely an aspect, overt or covert, they didn’t inflect.

Let me pause, lest anyone get their hackles up, and say this piece isn’t really about politics, let alone any particular political position. The form of liberalism Reiner was espousing pretty much died with the Great Society and continues to exist, if it exists at all, as little more than a historical artifact, not unlike the Know-Nothings and Abolitionists of the Antebellum period. Any resemblance between it and any current politicians and movements is almost purely coincidental.

By having the identity of the Van Dyke show spring so obviously from the New Frontier, Reiner unavoidably brought all its baggage in tow. It’s not to for one second diminish the genius of the series to say that it exhibits the smugness and elitism many, detractors and supporters alike, saw as that movement’s greatest flaw. Rob Petrie is college educated, lives in an affluent Northeastern suburb, and works in a glamorous industry in NYC—pretty much the perfect embodiment of the Liberal ideal, and a life practically no one actually lived but many aspired to.

The problem was that this somewhat utopian worldview could only work on TV—and only if you played by its rules. Its centerpiece was tolerance—but a kind of tolerance that was only feasible under a form of benign monarchy, laced with a heavy dollop of noblesse oblige, where Rob and Laura (as stand-ins for Jack and Jackie) were undeniably king and queen.

WATCHING DVD

Some might look askance at the idea of site called Cineluxe devoting an article—let alone a two-parter—to an old TV series. Two immediate rejoinders: TV always has been and always will be nothing but sitcoms and melodramas, so old really has nothing to do with it. And the Van Dyke show is one of the few pre-‘90s sitcoms that holds up well when viewed on a big screen.

The series was shot on 35mm by veteran cinematographer Robert De Grasse, who cut his teeth on RKO classics like Stage Door, the Rogers & Astaire Carefree, and the Robert Wise noir Born to Kill—which goes a long way toward explaining how a relatively low-budget 30-plus-episodes-a-year black & white sitcom looks so damn elegant. It’s not the last word in the filmic art, but it doesn’t look like it was shot in somebody’s closet either.

That it was all originally framed for 19-inch TVs—which means lots and lots of medium shots and closeups—isn’t as jarring as it could be, mainly because the material is so strong that you quickly shake off any twinges of claustrophobia. The big screen also tends to expose any dings, scratches, stains, or painted-over hinges in the sets—which are more beat up than they should have been—as well as continuity errors and shots saved in post by way of the optical printer.

The quality of the sound is all over the place, from season to season and sometimes from episode to episode within a season—and even with an episode. The last third of Season 3’s “Scratch My Car and Die,” for instance, sounds like they swapped out the boom mics for tin cans and string. Not that the audio for this series had to do much heavy lifting, but the too bland sound of the first two seasons tends to make the material feel flatter than it is and the actors more plastic than they are.

The release of the series currently streaming for free on practically any service you can think of is a pleasure to watch but looks like somebody went a little heavy with the edge enhancement. A new release done with a more delicate touch would be very much appreciated—and since it seems like the original 35mm sources are in decent enough shape, why not just do it in 4K next time?—although I’m not seeing where HDR would bring much to the party.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

The series reinforces this constantly, almost obsessively. The most blatant example is “My Husband is the Best One,” where it’s driven home that Rob is by far the smartest, most talented, and attractive person in the show’s universe (when Laura tells him, “You’re the best one and you know it, and so do I,” Rob responds, “Right!”) and that everyone else, other than Laura and including TV star Alan Brady, are mere peons (“Petrie is truly the genius behind the genius. The swift satirical sword belongs to him. Brady merely wields it.”). This is revisited in a more explicitly political context in the two-part Season 5 episode where Rob runs for councilman, where he’s seen as superior to a far more qualified candidate just because he’s taller and more personable.

The ultimate message of the Van Dyke show would seem to be that height and a kind of modest charm are the keys to ruling a benevolent society. There are constant references throughout the series to Rob and Laura’s attractiveness and a large number of episodes focus on how they’re pursued by almost everyone they come in contact with. Meanwhile, there are just as many reminders of the inferiority of everyone else in the cast—how Buddy is short and dumpy, Sally unattractive and old (Rose Marie was just two years older than Van Dyke), Mel a cringing marshmallow, Millie a snoop, a nag, and a lousy cook, Jerry an uncouth braggart, and Alan Brady a tyrannical, egotistical boor.

I could continue to cite examples—they’re legion—but you get the idea.

All of this fed from and helped reinforce the Camelot mystique, the myth, created largely via America’s popular-entertainment apparatus, of a young and vibrant couple that would lead the country into a prolonged and enlightened Golden Age. That all of course collapsed utterly after the assassination, with no one, inside or outside the Kennedy clan, able to assume the mantle—mainly because no one had a Jackie to go with their Jack. But the core of the idea—of the enthralling power of a mass-media-created political mythology—didn’t die; in fact, it was just getting on its feet and would ultimately lead to the rise of the cult of celebrity.

Part 2 suggests that while the values promoted by the Kennedy Administration and promulgated by the Van Dyke show were plowed under by the tumult of the ‘60s, they refused to rest in peace, and, mutated, rose again to permeate the current cultural landscape

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

Buddy, Sally & Mel—the bungled & the botched

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC