related article

“Rob Petrie was a model of decency and tact because he felt firmly grounded in his world; Michael Scott lashes out blindly because he feels lonely and lost.”

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

As a possible way of life, the Liberal movement of the early 1960s barely survived the Great Society and was in any meaningful sense kaput by the early ‘70s. The eruption of political radicalism and the resulting right-wing backlash—which made it clear the Liberal dream was not just untenable but vanquished—swept the myths that fed both the Kennedy mystique and The Dick Van Dyke Show into the dustbin of history. But for many, that mythology represented America’s best possible face, and even people who found it repugnant acknowledged its allure.

You can’t aggressively repress a potent cultural force fraught with unresolved emotion without expecting it to return—usually in monstrous form. Faced with a society that felt beat up, disoriented, and cheated after a decade and a half of constant upheaval, the late ‘70s conjured up retro as consolation. An unconscious admission that the present wasn’t good enough and all that turmoil hadn’t added up to squat, retro gave us an excuse to get lost in a vague haze of nostalgia. But by reinventing history to suit the needs of the present instead of accepting it on its own terms, creating a false sense of security based on a lie, it kept yesterday alive in ways that could only trouble today.

Initially created to smooth over a massive cultural void, retro was too tempting a fiction to not be turned to political ends, with TV the primary vehicle for its dissemination. From the ‘70s through the early part of this century, we defined our political identity by way of the tube. Whether via sitcoms, dramas, news shows, pervasive political ads—even children’s shows and wrestling—it provided a way to feel politically at home.

That all got supercharged with the emergence—more accurately, eruption—of social media, which thrives on fostering the illusion of free expression, interaction, immediacy, and intimate contact when it’s really just another form of entertainment. The pivot was reality TV, programs that made us comfortable with figures who were every bit as fictional as the ones on sitcoms and dramas but who we agreed to accept, out of a gaping emotional need, as actual. Once social media was able to add the illusion of access to TV’s illusion of reality, the door was wide open for creating a world ruled by influencers—people we flock to to define us because we don’t just admit to but feed on their superiority. Once all that became commingled with politics, the genie unleashed became an even more malevolent force.

All of this was set in motion, incredibly, by the Petries. Just because the whole influence thing has become hopelessly fragmented (deliberately so) didn’t mean it couldn’t coalesce in ways as powerful as a groundbreaking situation comedy able to command the rapt attention of more than a third of the nation. With the nuclear family dead and interred and a manic individualism—the very definition of atomization—on the rise, the idea of rallying behind a married couple that represents a national ideal is no longer tenable, but we can—and do—define ourselves against thousands of influencers who, considered as a whole (and once you allow for the huge redundancy factor), hold the same kind of sway over society. All of that fragmentation just ensures that the ground never feels quite solid under our feet.

As for the political dimension—there’s no need to spell it out, but I’ve left enough breadcrumbs along the way for anyone with a keen enough interest to follow the trail. Kennedy’s obvious successor, ruling-by-charisma-wise, was Regan—but, a product of the movies, he was ultimately just a trial balloon. It would take a figure clearly born of TV to make this whole thing virulent.

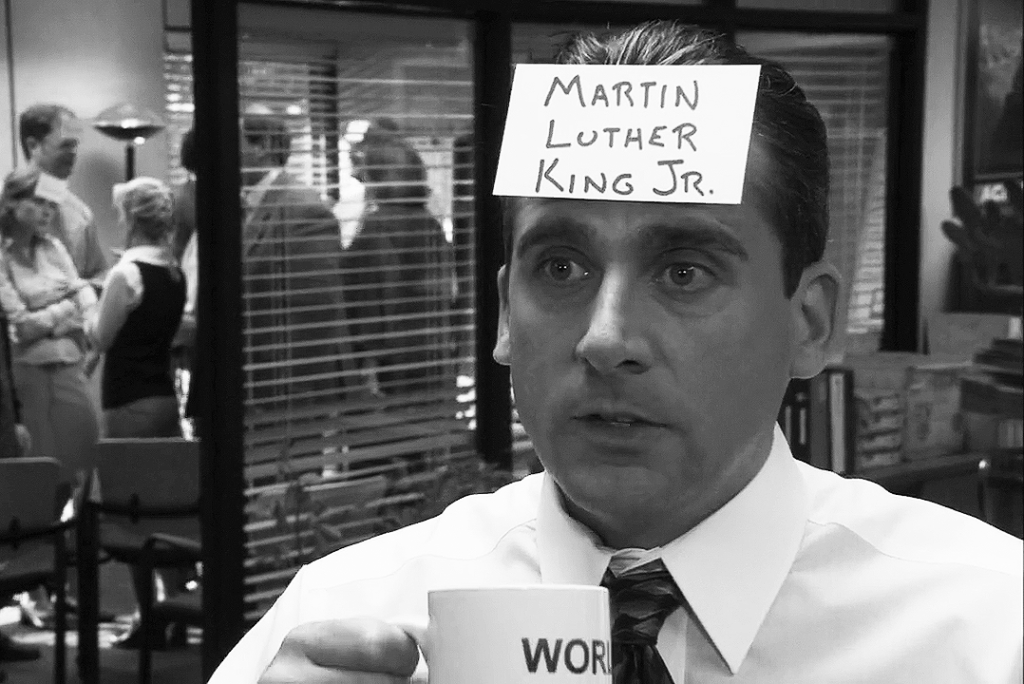

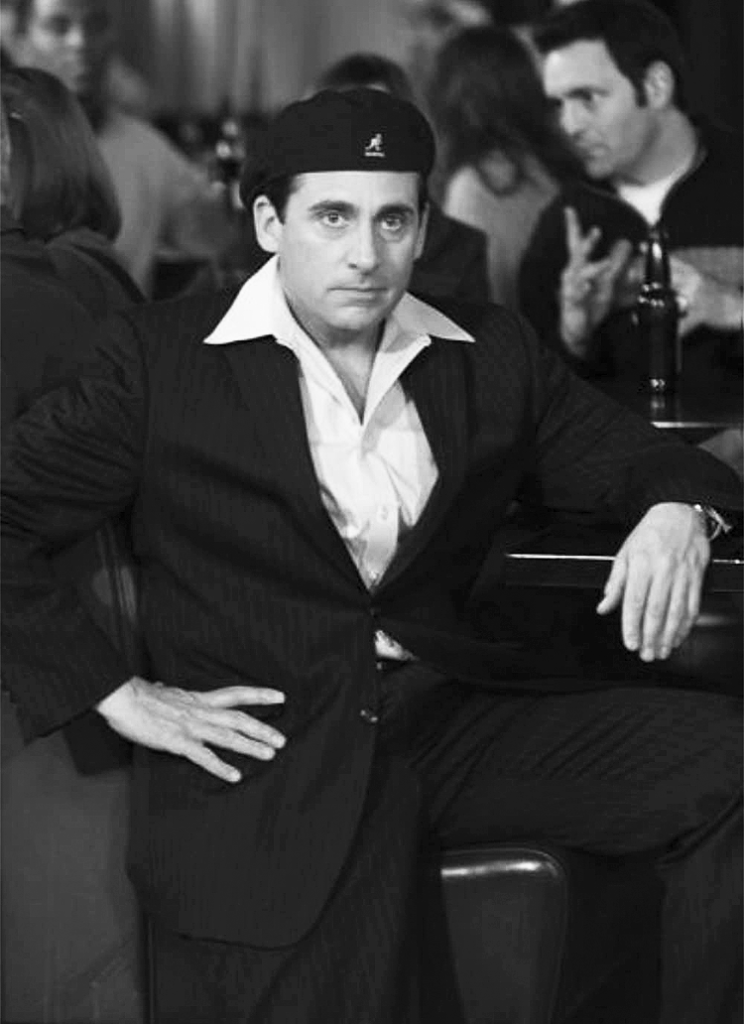

Which brings us to probably the most salient recent example of mutation via repression. Like a classic doppelgänger from the uncanny, Michael Scott couldn’t be further removed from Rob Petrie. But, as the bumbling male lead of an influential TV series about work, he and Rob obviously spring from the same sitcom roots, which lends them an unsettling resemblance. A charismatic figure warped to fit the present, Michael is little more than the sum of his flaws, a social cripple we find endearing mainly because we share his plight.

His defining character trait—and the point where he veers most radically from Rob—is the whole “no filters” thing, which allows him to get away with saying and doing things that are undeniably hurtful and offensive just because he’s seen as a well-meaning, hopelessly insecure dope. Rob was a model of decency and tact because he felt firmly grounded in his world; Michael lashes out blindly because he feels lonely and lost.

“No filters” has of course become a kind of rallying cry, a pernicious phenomenon no one would have trouble finding multiplying examples of in the wider culture—and something that couldn’t be farther from the world of the Van Dyke show. Brutality as grace is the price we pay for stumbling forward clueless, believing something potent will go away just because we succeeded in temporarily sweeping it under the rug. By refusing to understand and assimilate the past, we leave it free to constantly judge the present and, not surprisingly, find it lacking.

It should be obvious none of the above is meant to be an exercise in nostalgia—if anything, it was a meditation on the price we pay for nostalgia. Adopting the comforting shells of the past without pondering their meaning, or relevance, to fill a sense of emptiness in the present has only lead to massive discontent. Huddling inside outmoded forms as if they’ll somehow protect us from a storm of our own making has left us vulnerable, isolated, frustrated, and angry.

The answer isn’t to return to Rob and Laura’s world any more than it is to continue to obsessively, mechanically repeat our present mistakes. It could even be argued that our refusal to become unstuck from the past is the whole problem. But the past we continue to cling to bears practically no relation to the past as it actually happened but is more a kind of willy-nilly appropriation, a history’s greatest hits, a child’s form of succor. And no sane person could ever expect anything good to arise from a lie like that.

related article

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

“Honey, I’m Home!”

To provide a little potted Freud for context: The Return of the Repressed comes from Sigmund, and the core concept is that things once comfortable and familiar that we repress for whatever reasons will inevitably return to haunt us because we’ve never resolved how we feel about them. This led to his concept of The Uncanny, which Freud called “unheimlich”—or “unhomelike”—because what once protected and nurtured us re-emerges transfigured into forms that now threaten us instead. Overly reduced, the womb becomes the tomb. The whole notion of homelike become unhomelike obviously has a particularly pungent and ironic meaning when applied to a domestic situation comedy—the domestic situation comedy—of the early ‘60s.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC