Review: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

ALSO ON CINELUXE

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Tarantino takes a self-reflexive look at his body of work in his ninth film, which stays true to the look of its era

by Dennis Burger

updated June 5, 2023

There’s a truism about golf that focusing on your grip and overthinking your swing is the easiest way to sabotage your game. I’m not really sure how true that is because the closest I’ve ever gotten to a golfball field was the Mountasia mini-golf course that used to sit where my favorite barbecue joint now resides. But I’ve heard the same said of everything from tennis to endurance racing to sex so I’ll assume there’s some validity to it.

Given that, it’s sort of amazing Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino’s ninth and reportedly penultimate film, isn’t an absolute swing-and-a-miss. Throughout the film’s 160-minute runtime, it’s pretty obvious Tarantino obsessed over every aspect of not just this film but his entire oeuvre, as well as every single trope that has defined his style.

I won’t dig too much into the plot for numerous reasons but suffice to say the story centers on the relationship between an actor who is past his prime and the longtime stuntman who functions as his right hand, confidant, and personal assistant of sorts. The interactions between these two—played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Bratt Pitt, who turn in some of the best work either has ever committed to the screen—form the bedrock of what could almost be described as a tone poem about the end of an era, personally, culturally, and politically. It’s a rumination on the changing landscape of Hollywood and of society as a whole at the end of the turbulent 1960s.

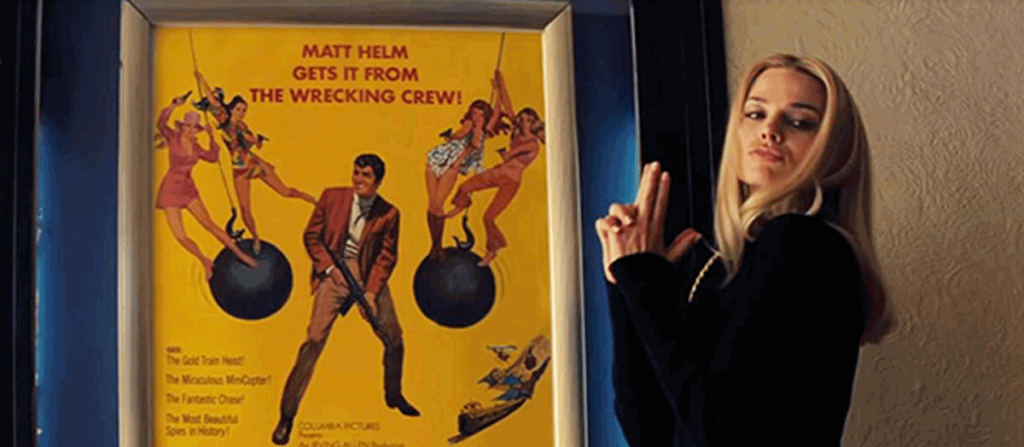

While DiCaprio and Pitt stand at the center of this loose tale, though, they can’t really be described as its heart. That function belongs to Margot Robbie, who positively mesmerizes as Sharon Tate, one of a number of real-world figures who populate the wholly (and I do mean wholly) fictionalized world of Tarantino’s film.

His handling of Tate as a character is honestly one of the film’s most fascinating elements. He doesn’t put her on a pedestal, objectify her, or turn her into some magical, mythical, or tragic creature. He instead humanizes her, to a degree I’ve never seen in any of the fictionalized or dramatized portrayals of her. Combined with Robbie’s pitch-perfect portrayal, this gives her a presence that feels somewhat out of proportion with her relatively limited screen time, not to mention the minuscule amount of dialogue given to her.

Once Upon a Time leans hard on a number of tried-and-true Tarantino tropes, though not always in the expected ways. As always, pop music plays a huge role in the soundtrack, though Tarantino seems less interested in digging up long-forgotten deep cuts like “Stuck in the Middle with You” or “Flowers on the Wall,” relying instead of iconic cuts that evoke the era and the personal emotions he’s exploring.

Another trope he seems to be consciously grappling with is violence. I’ll admit, I’ve never had the problem with his use of gore and splatter as some critics, if only because it’s generally so over-the-top and obviously cartoonish that there’s only the most tenuous relationship between his violence and real-world bodily harm. In Once Upon a Time though, not only is the violence massively downplayed, it’s also shockingly realistic. That combination—the overall lack of bloodshed combined with an undeniable lack of glorification or sensationalism when it does appear—honestly makes the two or three brief violent scenes the exact opposite of cartoonish. In fact, they’re so brutal as to be difficult to watch.

It seems to me this is intentional. Indeed, one of the minor recurring themes is the representation of violence in movies and TV (including Tarantino’s own previous efforts). Unsurprisingly, it’s a theme he handles with a hefty helping of Gen X irony, but the fact that he’s handling it so blatantly in the first place can’t go unnoticed.

You also can’t help but notice that Tarantino agonized over the look of the film. Shot on a combination of 8mm, 16mm, and 35mm film stock, the color portions are outright dazzling, even if the image seems to be a revolt against current digital video standards. If you’re a videophile, be prepared for some seriously crushed blacks, overly ruddy skin tones, primary colors that sizzle with near-neon intensity, and a defiant lack of dynamic range, especially on the lower end of the value scale.

I don’t say this as a criticism of the home video transfer. The Ultra HD/HDR presentation on Kaleidescape seems absolutely true to Tarantino and cinematographer Robert Richardson’s artistic vision. I’m merely giving you a heads-up that if you go in expecting near-infinite shadow detail and subtlety in the color palette, you’re going to be a bit taken aback by what you see here.

On the other hand, this is one of the few modern films that genuinely takes advantage of Ultra HD resolution, since it was finished in a 4K digital intermediate. The wider color gamut, as compared with the older HD home video standards, allows the extra intensity of those vibrant primary hues to shine through unscathed.

Interestingly, despite the overall lack of dynamic range on display, there is one very dark scene that would have benefited from the dynamic metadata of Dolby Vision HDR. I know a Dolby Vision master was created for digital cinema exhibition, although the best we have on home video is an HDR10 grade that does a wonderful job of handling the one or two rare instances of high-intensity brightness, most notably in the TV-pilot-within-a-film that comprises so much of the second act.

Overall, it’s a gorgeous film that is well-served by this home video presentation. It simply isn’t what most people would consider home theater demo material, because it has absolutely no interest in acting as such.

The lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 soundtrack accompanying the Kaleidescape download also does a wonderful job of delivering the film’s mix, which runs the gamut from safe and unobtrusive to unapologetically playful, depending on the needs of the scene. There are creative uses of the surround soundfield that will likely go unnoticed unless you’re taking notes and critiquing the mix from a technical perspective, and other, more obvious surround-sound tricks that seemingly serve Tarantino’s meta-purposes of making a film about filmmaking. But all of this really takes a backseat to what matters most: The fidelity of the soundtrack music and the intelligibility of the dialogue, both of which are unimpeachable.

For those who love some of Tarantino’s films and outright loathe or are bored to tears by others, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is an interesting work. It isn’t perfect or consistent, but it is utterly captivating—so much so that I’ve been unable to think about much else since watching it.

Will it stand the test of time? Who knows? I will say this, though: After taking a bit more time to sort out my own thoughts on the film, I’m eager to dive back in and explore it at least one more time.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

PICTURE | This gorgeous film is well served by Kaleidescape’s Ultra HD/HDR presentation, which seems absolutely true to what Tarantino and cinematographer Robert Richardson intended

SOUND | The DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 soundtrack does a wonderful job of delivering the film’s mix, which runs the gamut from safe and unobtrusive to unapologetically playful, depending on the needs of the scene

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC