Review: Rear Window

related reviews

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

The 4K transfer exposes both the good and the bad of Hitchcock’s best-known film, but ultimately offers a satisfying way to re-engage with a classic

by Michael Gaughn

September 19, 2020

As I mentioned in my Psycho review, more has been written about Hitchcock than any other filmmaker—and more has probably been written about Rear Window (1954) than any other film. It and Vertigo (1958) are often considered his most accomplished efforts—a conclusion I would vigorously dispute, but not here. Rear Window has gotten the most attention because, between the two, it’s the squeakier wheel.

It’s undeniable that this hubristic exercise in artifice, or stagecraft as cinema, would have completely unravelled in the hands of a lesser filmmaker. And it remains impressive how much Hitchcock is able to make the pure contrivance of his elaborate set a big part of what makes the film so engaging. You almost don’t care that it’s the epitome of mid-’50s Broadway set design. There’s something about its sheer physicality that makes everything that’s presented on it feel convincing.

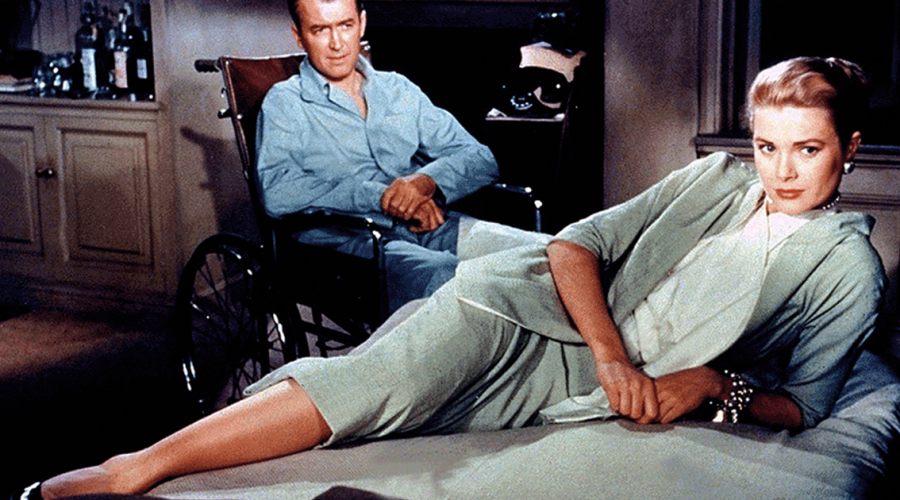

Because Hitchcock was relentlessly ambitious, his reach constantly exceeded his grasp, so Rear Window has more than its share of shots that don’t quite work, storyboard concepts that had to be triaged in post, characters that could have used a little more development. Thelma Ritter’s part is ridiculously overwritten, and you can feel her pausing for laughs that faded it into the void more than five decades ago. Grace Kelly is just a little too Grace Kelly, with a patrician accent that can’t help but grate on modern ears.

The film works mainly because of the ingenious way Hitchcock makes the set, with its vignettes, convincing as projections of Jimmy Stewart’s various states of mind, making the film from early on feel dreamlike. And it works because of Stewart’s performance. He, pre-World War II, was a good, even great, actor—his work in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is jawdropping, even today. But he was also kind of lightweight, sometimes clownish. After the war, there’s an undeniable sense of experience behind his eyes that he was able to employ deftly in his best roles—like in the Anthony Mann westerns, in Vertigo, and here.

Not that his performance is flawless. As always with Hitchcock, there are weak moments in the script and in the direction that cause Stewart, adrift, to lapse into his patented Stewartisms. But in the hands of a more traditional Hollywood pretty boy type, L. B. Jeffries snooping out of the back of his apartment could have seemed just comic, or even diseased. Stewart creates a perfect tension between making it all seem justified and also the dangerous preoccupations of a troubled soul.

The 4K HDR presentation is a must-have for anybody who even thinks they care about movies—not because it smooths over the flaws but because it presents everything honestly, the good and the bad. Seeing Rear Window in any other format inevitably puts you at a distance from the film, which inevitably places you at too great of a distance from what’s going on in the apartments across the way. You need to see it at this resolution to get pulled back into the film, so it stops feeling quaint and again becomes relevant and compelling.

The flaws are pretty egregious. Hitchcock, of course, endlessly obsessed over how to present Kelly, but there’s a shot at 29:51, during a sequence meant to scream “beguiling beauty,” where she looks like a walking corpse. Even more jarring is a closeup at 1:50:29 of the hapless Wendell Corey that looks like it was originally part of a wider shot that was ruthlessly enlarged on an optical printer.

For whatever reason, cinematographer Robert Burks didn’t do as good a job here as he would on Vertigo, but for everything that takes you out of the film, there’s plenty to keep you engaged. Probably no other movie has better conveyed the feel of New York at sunset, or especially at three in the morning. And, while the HDR makes its presence felt just here and there, it is an absolute revelation during the climax. Anyone who knows Rear Window will know exactly where I’m going with this, but Raymond Burr being blinded by Stewart’s flashbulbs fell solidly into the “suspension of disbelief” camp until now. Presented in HDR, those white flashes become searing, making you feel Burr’s disorientation and sense of absolute loss. Rear Window is worth seeing in this form just for that moment alone.

The audio is “only” DTS-HD Master Audio stereo. I used quotes because the thought of somebody mucking around with Hitchcock’s innovative and masterful sound mix to take it into the land of Atmos is both terrifying and nauseating. In the right hands, it could definitely enhance the experience—but who’s got the right hands? And I think there’s a good chance an enhanced sense of spaciousness could actually end up emphasizing the one-dimensionality of a lot of the stagecraft.

The mix here does a great job of allowing you to savor what Hitchcock originally wrought, where he used mainly volume, timing, and reverb to convey the sense of voices and other sounds heard in various spaces and from various distances away. The soundtrack, as is, is so strong it could almost stand on its own as a radio play.

But allow me just a brief swipe at Franz Waxman’s score, which is the weakest link in the film. It’s not that I don’t like Waxman—his work on Sunset Boulevard represents the pinnacle of the film-scoring art—but he’s just not in sync with this film at all. The opening theme—if you can call it that—is a hackneyed pastiche of Gershwin clichés—42nd Street meets The Naked City. But what makes it really fall flat is the sense of complete disconnection from the evocative use of source cues that makes up the rest of the soundtrack. I know Hitchcock was aiming for a kind of overture as the curtains literally went up, but he missed the mark.

And then there’s that song. Another of Hitchcock’s offerings placed on the altar of Grace Kelly, it was a great idea in concept—show a composer struggling to write a song to parallel Jimmy Stewart’s conflicted feelings about Kelly and then have it all come together as an example of songwriting perfection. Problem is, the song sounds fully worked out—and not very good—from the start. Had it been great, it could have really enhanced the film—and not made the salvation of Miss Lonelyhearts look like the worst kind of Victorian contrivance. But “Lisa” is a real stinker.

I’m not a big fan of Top 10 or Top 100 or whatever lists—they’re almost all laughable when they’re not outright dangerous. So let’s just say that Rear Window, for too many reasons to ignore, is an essential. Not only does it stand on its own as entertainment for all but the most jaded contemporary audiences, but its reverberations can still be strongly felt in filmmaking in the present. In 4K HDR, it becomes not just another movie, but a glimpse of the very wellspring of cinema.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | This 4K HDR presentation is a must-have for anybody who even thinks they care about movies—not because it smooths over the flaws but because it presents everything honestly, the good and the bad

SOUND | The stereo mix does a great job of allowing you to savor what Hitchcock originally wrought, where he used mainly volume, timing, and reverb to convey the sense of voices and other sounds heard in various spaces and from various distances away

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC