Review: Rosemary’s Baby

also in Reviews

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

The film that created the modern horror/thriller genre looks fine in Blu-ray-quality HD but cries out for 4K HDR

by Michael Gaughn

October 22, 2020

1968 saw the lowest movie attendance in history. It was also the year of 2001, Once Upon a Time in the West, The Night of the Living Dead, If . . ., The Producers, Bullitt, The Party, Petulia, Planet of the Apes—and Rosemary’s Baby. In other words, the movies that would reinvent Hollywood and define it for the next 50 years.

Coincidence? Of course not—and it’s exactly that creative ferment born from cultural strife that gives me hope this eerily similar era might lead to another radical reinvention of the movies. Because boy do they (and we) need it.

But that’s a topic for another day. The focus of attention here is Roman Polanski’s genre-defining, damn near perfectly calibrated horror/thriller Rosemary’s Baby. And let’s get one thing clear right off the bat: This is not a serious film, let alone an art film. Polanski knew full well he was making a trashy potboiler and didn’t care. He wanted to know what it felt like to create a big hit within the studio system, and he did. He hit the jackpot.

That’s not to say that Polanski colored within the studio lines. He toys with both the studio conventions and a very wary but looking to be jazzed audience the way a cat torments a half-dead mouse. The movie gets its big perverse kick from seeing how far it can push the boundaries without breaking them. There’s the continual sense that this stuff shouldn’t be happening in a mainstream crowd-pleaser and yet it is, which makes the film, beyond its subject matter, feel very much like a nightmare. But that approach has since become so commonplace that it’s lost its impact—which means you have to approach Rosemary’s Baby on its own terms and with fresh eyes if you’re going to get anything out of the experience at all.

There’s barely a frame that doesn’t bear evidence of Polanski’s lightning-quick paw, but probably the most striking example, especially since it essentially sets the whole grisly machine in motion, is Teresa Gionoffrio’s suicide juxtaposed with the entrance of the Castevets. We go from shots of a woman’s head framed in an improbable amount of blood (Weegee never photographed a crime scene that gory) to a seemingly incongruous low angle of two archetypal geriatric Manhattan flânuers strolling toward the camera dressed like they just came from Mardi Gras. The whole sequence is as disconcerting as it is hilarious. It’s like, “OK—I just got my first big, gruesome shock, so why am I laughing?” It’s Polanski’s way of saying you’d better trust him on this ride or you should just go watch another film.

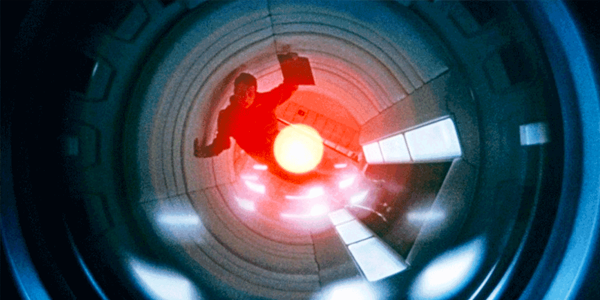

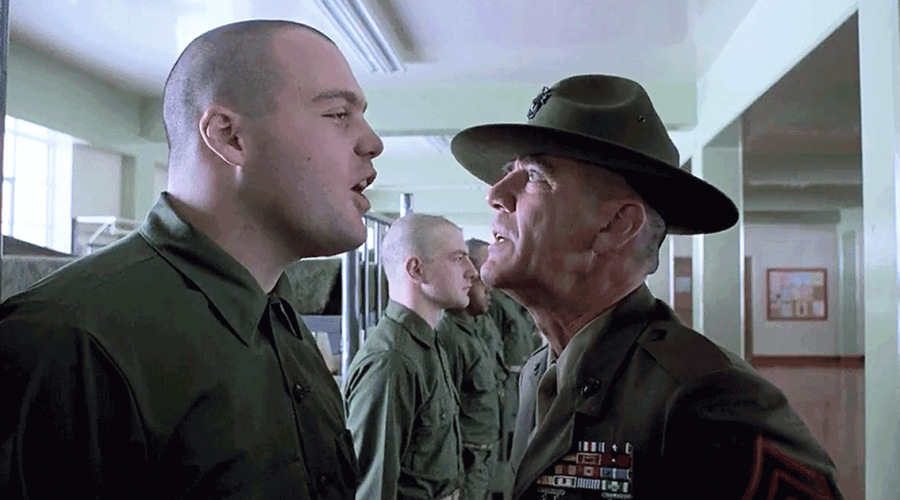

There’s no point in recounting the plot or the set pieces. If you’ve seen the movie, you know all of that well; if you haven’t, why spoil it for you? What’s worth underlining is that—like Kubrick’s The Shining, which owes Rosemary a huge, and amply acknowledged, debt—Rosemary’s Baby still works. I know it’s arguable, but I don’t think anyone’s ever pulled off anything as odd yet apt—perverse yet airy—as the elaborate ritual leading to Rosemary’s insemination, where she’s granted an audience with a Samsonite-lugging Pope while being straddled by Satan.

The film has flaws but Polanski, out of sheer creative exuberance and guile, manages to trump them all. He’d wanted Robert Redford for the lead, which would have been amazing. He got John Cassavetes instead—which would have sunk the whole enterprise under the hand of a lesser director. Cassavetes acts like an asshole from the very start, so of course he’d sell his soul to the Devil. And yet the film somehow manages to glide right over that major lost opportunity.

I was also struck watching the movie this time by what an outright flake Mia Farrow’s Rosemary is. I realize Polanski wanted to keep the audience wondering if all of this was happening in the character’s head, but this Antichrist-toting Midwesterner is such a dim bulb that you almost don’t care if she’s delusional to boot.

And I have to ask: If Farrow is a housewife and Cassavetes is a struggling actor, where did they get the money to rent an Upper West Side apartment that would easily sell for many millions today?

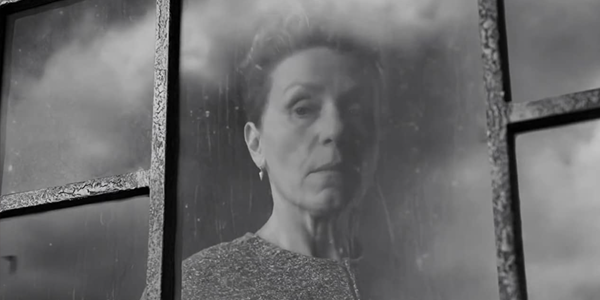

I’ve never had a chance to see Rosemary’s Baby in a theater, so watching it in HD on Kaleidescape was a better than expected experience—that only made me long to see it in 4K. William Fraker’s cinematography was more compelling than I’d remembered from other home video incarnations—although I would hope that going to the next level of resolution will help minimize that damn flashing they used throughout when printing the film. It seriously dates what would have otherwise been an exquisitely photographed movie (and will forever haunt a large number of otherwise excellent films from the late ‘60s through the ’70s).

Christopher Komeda’s weird gothic-jazz soundtrack, bringing the evil of the East European woods into ‘60s Manhattan, still holds up, partly because it’s applied sparingly instead of being blared wall to wall. And this, like Rear Window and The Birds, is yet another older film that would seem ripe for an Atmos makeover, but it has such an ingeniously done original audio mix that expanding the surround field wouldn’t necessarily make it more atmospheric. That said, as with those other two films, I’d be intrigued to see somebody give it a shot.

To repeat myself: Nobody needs to convince you to watch Rosemary’s Baby. Its reputation as a horror classic is unassailable and secure. But I would urge you to first scrape away as many of the accreted conventions Polanski’s shocker has spawned and try to see it as if all those other films had never happened, as this is the place where it all began.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Watching this in HD on Kaleidescape is a better than expected experience, with William Fraker’s cinematography more compelling than it’s been on other home video incarnations

SOUND | Christopher Komeda’s weird gothic-jazz soundtrack, bringing the evil of the East European woods into ‘60s Manhattan, still holds up, partly because it’s applied sparingly instead of being blared wall to wall

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC