Review: Big Fish

review | Big Fish

4K HDR restores the impact of 35mm film to what might turn out to have been Tim Burton’s last great movie

by Dennis Burger

January 6, 2022

More than almost any other film, it’s nearly impossible for me to be objective about Tim Burton’s Big Fish. For one thing, I almost had a bit part in it but that fell through. For another, it was filmed—almost literally—in my back yard. My niece attends the private college that stood in for Auburn University in the picture. My wife and I often take long walks through the dilapidated sets of the Town of Spectre, which is on an island just north of town and serves these days as a goat sanctuary.

But all that takes a backseat to my feelings about Tim Burton’s body of work and Big Fish‘s place in it. As a huge fan of his earlier films, I found this one to be a welcome return to form after the disappointing Sleepy Hollow and Planet of the Apes. It really felt like a potential turning point for Burton. I saw Big Fish as a new beginning, the first step on a journey that had a more genuine human element, without so much of the affected weirdness Burton became known for after he stopped being a legitimately weird outcast and transformed into a popular Hollywood darling. Instead, it ended up being his second-to-last legitimately good film and his final worthwhile live-action work. So it’s hard for me to watch Big Fish and not get distracted by thoughts of what could have been.

But you don’t care about any of that, do you? Nor should you. Chances are good that if you’re reading a review of a nearly two-decade-old film, you already know exactly what you think about it. You just want to know what it looks like in 4K and how well the new Dolby Atmos mix works with or against the material.

Long story short: Both are astonishing. Big Fish has never been a film that worked well on home video, as the tired old Blu-ray master was overly soft with a weirdly unbalanced and idiosyncratic color palette that did the cinematography no favors.

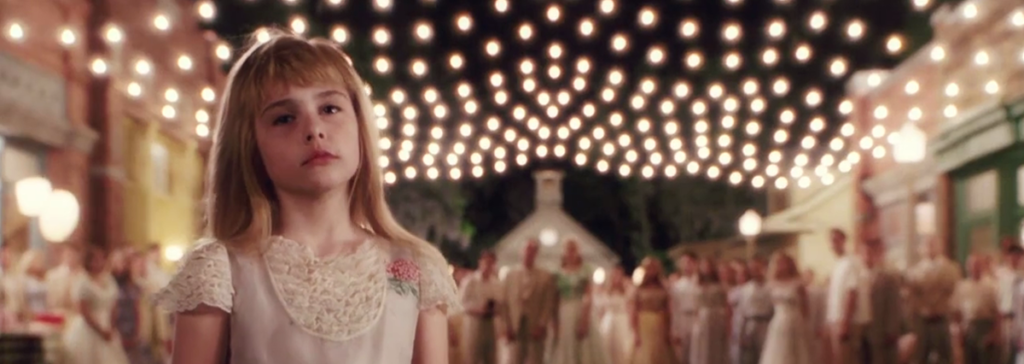

By contrast, the new UHD/HDR presentation is revelatory. Don’t get me wrong—this is still a somewhat soft and gauzy image. There isn’t a razor-sharp edge to be found within its 125-minute runtime, even in closeups. But the increased resolution of UHD and—one assumes—the new scan of the negative unlock textures in the faces, fabrics, and environment that the old Blu-ray never even hinted at. There’s also a delicious bed of organic film grain Sony thankfully saw fit to leave alone, so you’ll see none of the digital noise reduction and subsequent edge enhancement that so often plagues films with similar aesthetics.

What you end up with is what was on the photochemical film—nothing more, nothing less. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. In addition to the rich textures and the palpability they lend to the film, the new HDR grade also unlocks subtlety in the color palette I had long since forgotten existed. Skin tones are consistent throughout, and the larger gamut gives the image room to be muted when it needs to be and intensely saturated when appropriate. Kaleidescape’s HDR10 presentation is also abundant with lovely shadow detail, and although you won’t spot many if any eye-reactive extremes of brightness (although the nighttime sequences in Spectre make for a dazzling display of shadow and light), there’s enough bandwidth in the value scale to give the image a wonderful sense of depth and dimension. It deserves to be seen on the best screen you have access to.

In terms of the audio, I didn’t notice at first that Kaleidescape’s download comes with a new Dolby TrueHD Atmos mix. Don’t take that to mean there’s nothing going on in the overhead channels. There is. But the mix is so well-balanced and thoughtful that the overhead effects don’t draw your attention away from the screen. For the most part, they serve as connective fabric between the all-important front soundstage and the surrounds, making the entire mix more cohesive and far more immersive. Dialogue intelligibility is fantastic, and there’s a wonderful richness and warmth that works to the benefit of Danny Elfman’s score.

I’m going to go out on a limb and guess this was somewhere in the neighborhood of my 30th viewing of Big Fish at home. But this was the first time I was able to set aside all of the intrusive thoughts I mentioned above and just soak in the film on its own terms. That’s how good this UHD HDR presentation is. It is, at the risk of sounding hyperbolic, like looking at projected 35mm.

And as the credits rolled, I did get hit with that unshakable bittersweetness that arises from this being one of my favorite Burton films but also his last good one. But for just over two hours, I was able to put all that down and get lost in this magical but all-too-human movie, with its spectacular environments, ridiculous scenarios, and tender sincerity. The long and short of it is, this new UHD release captures Big Fish‘s essential cinematic nature in a way no previous home video format could come close to replicating.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

PICTURE | This UHD/HDR presentation is revelatory, with the increased resolution unlocking textures in the faces, fabrics, and environment that the old Blu-ray never even hinted at.

SOUND | The Atmos mix is so well-balanced and thoughtful that the overhead effects don’t draw your attention away from the screen but instead serve as connective fabric between the front soundstage and the surrounds.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC