Review: Once Upon a Time in the West

also on Cineluxe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Sergio Leone’s legendary epic finally makes the leap to 4K HDR with mostly admirable results

by Michael Gaughn

May 8, 2023

Once Upon a Time in the West has been on the short list of titles I’ve wanted to see in 4K HDR ever since the format was announced. And now that the day has arrived, my reaction can be summed up in two words: deeply ambivalent.

There’s no denying it looks striking, worthy of all the usual praise about pristine reproduction, fine detail, piercing highlights, rich, nuanced blacks, etc. But, interrupted by a call, I had to pause playback during Jason Robards’ big entrance at Lionel Stander’s trailside store, and when I came back and hit Play again, something didn’t feel quite right. I’d been enjoying the movie, but having been jolted out of it, I suddenly realized it just didn’t look like film. And once I’d been thrown for that loop, it became hard to buy back into the illusion.

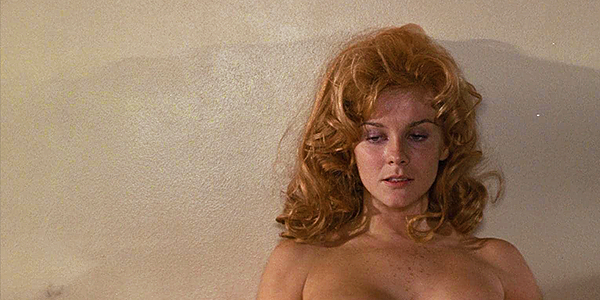

The faults in Once Upon a Time are nowhere near as egregious as they are with HDR transfers like The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, or The Godfather, where you’re forced into a cartoonish parallel universe that bears little relation to what was originally committed to film. The intentions here seem to have been more honorable—they just took it all a little too far. A Sergio Leone western from the late ‘60s ought to have grain, which brings energy and texture to the frame. And smoothing everything over once again results in skin that looks a lot like pleather. (The Victor Laszlo Award this time around goes to Robards, with Claudia Cardinale coming in a close second.)

Film has signature traits that create a kind of analog aura that makes movies of the pre-digital age feel more human. But we’ve come, sadly, to see those traits as flaws, which is why tech guys running roughshod over classics tends to elicit nary a whimper when it ought to summon up howls. To use 4K HDR to impose a radical makeover when it could instead be used to make the home viewing experience match what it was like to see the film as it was originally shown in theaters feels criminal.

To give credit, it was nice to see things like the subtle gradations of the worn black fabric in Jack Elam and Woody Strode’s hats so well rendered, and in a film that thrives on extreme closeups, you can make a parlor game out of counting nose hairs and ferreting out scars. But I’m not sure how anyone benefits from being able to make out every line in Cardinale’s crow’s feet or all the innumerable tire tracks criss-crossing the desert, or any of the other things we were never meant to see. And this is another transfer where HDR makes some of the elements pop far too much. The fire Cardinale uses to warm her coffee looks out of line with both the film and reality, and the railroad baron’s blinding white shirt collar and cuffs float in the frame like the Cheshire Cat’s smile.

It was interesting to compare this new release to the recent straight 4K transfer of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (GBU). That earlier film is alive with grain, which does at times make its presence too emphatically felt; but the movie would lose much of its warmth and grit if it was all scrubbed away. Some of the elements are in questionable shape, causing some scenes to look a little flat and washed out. But you ultimately end up with an experience that’s remarkably true to the film Leone shot, which ought to be the goal.

(Adding to my ambivalence—and to get heretical here for a moment—rewatching GBU had me wondering if it isn’t the better movie. Its looser, droller, but still epic approach makes Once Upon a Time seem a little too aware of its own importance. Both films have been equally influential but in different ways, and GBU, which has little of the pretentiousness but all the ambition of the later effort, might actually be the more satisfying of the two.)

There isn’t much point in talking about Once Upon a Time as a film. What Leone created has become so iconic and has so permeated the culture that everyone is familiar with it, even if they’ve never actually seen it. But I was struck on this viewing by how almost all the conventions that determine modern film were born during that incredibly fecund period between 1967 and 1969, and by how stagnant things have gotten in the half century since, until the movie industry has become a kind of vast—but unquestionably lucrative—necropolis.

And I’m not just talking about film techniques but subject matter, tone, attitude, acting—the whole shebang. (To take just one example, Tarantino wouldn’t have a career without Once Upon a Time, and everything he’s done has essentially been a recapitulation of Leone, just cranked to 11.) Nobody ever seems to wonder why we’ve never moved beyond—outgrown—that era. It would be too much of a digression to speculate on that here, but it does seem to be a enervating case of massive repression.

But to return to the film at hand—which, in a sense, we never left—while Once Upon a Time in the West shows evidence of the tendency toward cockiness in recent 4K HDR transfers, and would have been amazing (and a candidate for our “Essentials” list) if it had shown just a bit more respect for the source material, it is enjoyable to watch, partly because the strength of Leone’s original effort allows this release to rise above its digital sins. It will do—and do well—for now while we hope the idea of trying to stay true to the filmmakers’ intentions makes a badly needed comeback.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC