Want to Dig Deeper Into the Mandalorian?

related articles

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

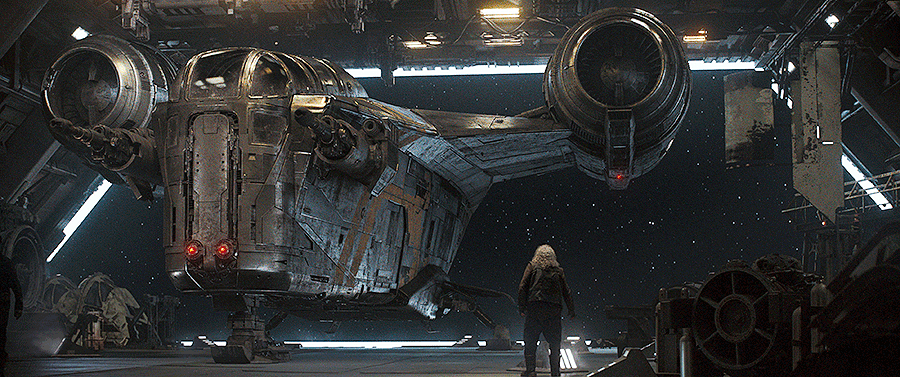

Season Two shows just how deeply this Disney+ series is woven into the Star Wars universe

by Dennis Burger

January 2, 2020

It’s difficult these days to have any meaningful discussion about Star Wars without obsessing over The Mandalorian. This lightning-in-a-bottle Disney+ series has the sort of universal appeal that none of the main saga films have enjoyed since The Empire Strikes Back. (And let’s not forget that TESB wasn’t so universally beloved until years after its initial release.)

There’s good reason for the series’ universal appeal, of course. As I said in my wrap up of the first season, The Mandalorian is a wonderful deconstruction of everything that made the original Star Wars such a smash hit. In breaking the galaxy far, far away down into its essential components (the gunslinger, the samurai, the strange-but-familiar environments, the wonderful sense of mystery, the thematic through-lines of honor, familial baggage, and redemption) and recombining them into a shape we’ve never quite seen before, the series continues to be both stimulating and comfortable, both innovative and grounded in the past.

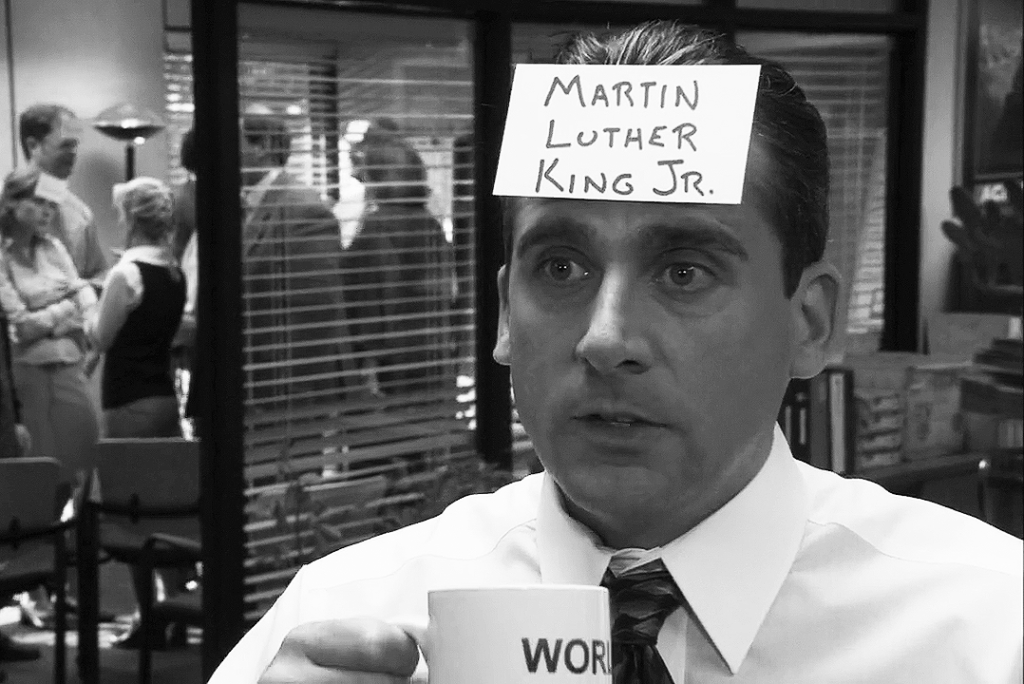

One thing I said about the series’ first season no longer rings true after the second batch of episodes, though. In my Season One overview, I made an offhand comment about the show’s “tenuous connections to the larger mythology,” despite the fact that that season ended with the appearance of one of the most legendary Star Wars weapons of all time: The Darksaber.

In Season Two, the connections to the legendarium become much less tenuous, much more overt, and much more central to the underlying themes and meaning of The Mandalorian. And it’s that last point that’s most important, because the simple truth is that you don’t really need to know the history of Mandalorian culture or its various factions to follow the plot of this past season. That history simply helps in unpacking what it all means.

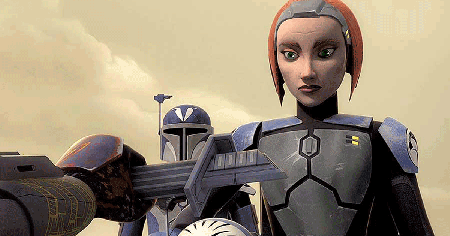

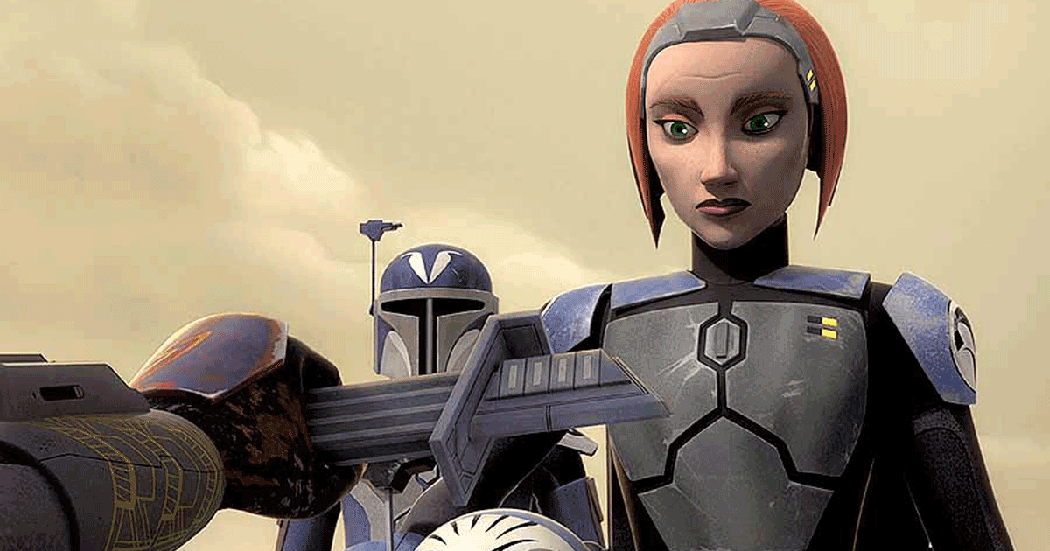

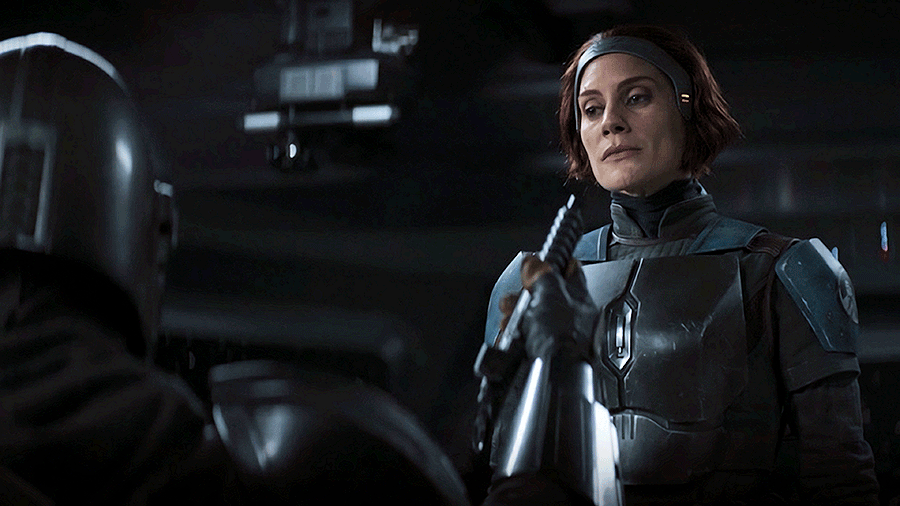

And I can say that pretty confidently, because I talk to so many of my friends who are absolutely gaga over “new” characters introduced in Season Two who aren’t new at all. Characters like Bo-Katan Kryze, played to perfection by Katee Sackhoff not only in this live-action series but also in three seasons of The Clone Wars and one particularly memorable episode of Star Wars: Rebels. I was worried, when rumors of Bo-Katan’s return started circulating on the internet, that she would feel shoehorned into this series, that her presence would feel like fan-service of the worst sort. Nothing could be further from the truth, though. To misquote Voltaire, if Bo-Katan hadn’t already existed, it would have been necessary to invent her for Season Two to make a lick of sense.

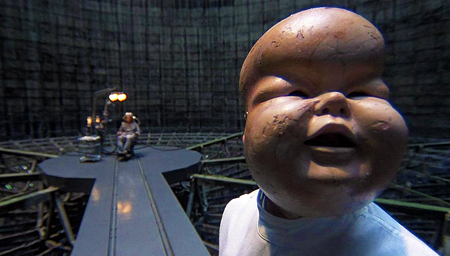

This season also features the return of Ahsoka Tano—perhaps the single most beloved character ever created by George Lucas, but one that many fans of The Mandalorian had never heard of or only knew secondhand thanks to hyper-nerds like myself. Again, though, due to the way showrunners Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni have woven her into this series, you don’t really need to know Ahsoka’s backstory to understand her mission in The Mandalorian. But I would argue that you do need to know where she has come from and where she’s going if you want to truly understand why she’s on that mission.

The point I’m trying to not-so-subtly make here is that you can go into The Mandalorian having only seen the original Star Wars films and not really feel like you’re missing anything essential in terms of plot. You may get the sense that there’s a larger story unfolding that you’re not privy to, but that’s always the case with any good Star Wars story. But if you haven’t watched The Clone Wars and Star Wars: Rebels, you actually are missing out on a deeper level of understanding that’s just sitting there waiting for you to discover.

I’ll give you just one example, although I feel the need to throw out an obligatory spoiler warning here for those of you who are making your way through Season Two slowly in an effort to ameliorate some of the pain caused by the long wait for Season Three.

In the epic finale of this season, there’s a moment in which Din Djarin, the titular Mandalorian, offers the Darksaber to Bo-Katan after being informed of its cultural significance. This moment almost perfectly mirrors a scene from “Heroes of Mandalore,” the Season Four premiere episode of Star Wars: Rebels. There, a Mandalorian named Sabine Wren offers Bo-Katan the blade and Bo-Katan accepts it, although not without some hesitation. In the season finale of The Mandalorian, she rejects it outright. And I won’t get into all of her political reasoning for doing so, as the episode spells all of this out. My point here is that the mirroring of these two scenes adds an extra level of tension to the finale and quietly tells a tale we haven’t seen unfold in any form to date.

The fact that Bo-Katan refuses to simply accept the Darksaber this time around, when we’ve seen her do so before under nearly identical circumstances, tells us something about the character that no amount of exposition could convey nearly as artfully. Namely, it tells us that she blames herself for the so-called Great Purge of Mandalore and the genocide of her people, an event we’ve only heard about in rumors and retellings.

I could go on and on, rambling about little nuggets of this sort you can glean from viewing The Mandalorian in the context of its animated forebears, and I’ve done so in private conversations with friends who love the live-action series but seem hesitant to watch “kids’ cartoons.” It honestly doesn’t help my case that The Clone Wars didn’t start off with a bang. Even as a devoted fan, I have to admit that the first season was childish and wildly uneven.

But by Season Two, The Clone Wars gets good. Really good. By Season Three, it’s honestly some of the best Star Wars ever made. And by Season Four it transforms into one of the best TV series of all time, subject matter be damned.

So, if you’ve tried getting into The Clone Wars and found it a tough pill to swallow, I recommend giving it another try—but this time around, skip the bulk of the first season. Watch “Rookies,” the fifth episode, then skip to the final four episodes in that first run: “Storm Over Ryloth,” “Innocents of Ryloth,” “Liberty on Ryloth,” and “Hostage Crisis.” Objectively, they’re nowhere near the quality of later seasons, but they’ll give you a good foundation for what’s to come, especially the second-season episodes that really lay the foundation for The Mandalorian, starting with Episode 12, “The Mandalore Plot.”

Likewise, Star Wars: Rebels gets off to a similarly uneven start, and I wish I could give you a similar cheat sheet for which episodes are skippable. But you’ll just have to trust me on this one: By the time you get to the end of Season Four, it becomes clear that there wasn’t a throwaway moment in the entire 75-episode run. It’s simply one hell of a slow burn.

All seven seasons of The Clone Wars and all four seasons of Rebels are available to stream on Disney+, and it’s worth noting that the streaming provider presents the former with all of the content that was censored by Cartoon Network in the original broadcasts. Don’t go in expecting anything overtly gratuitous or vulgar, but I often advise my friends with young children that the series explores the implications of war in a way pre-teens aren’t quite mature enough to digest. So take that for what it’s worth.

Of course, we can’t know for sure how much of an impact the events of The Clone Wars and Rebels will have on future seasons of The Mandalorian, especially given that there’s no clear and obvious path forward for the series. Taken as a whole, the first two seasons of this wildly popular live-action show have told the tale of a man whose sense of self was predicated on a moral code that he never questioned—until forced to do so. It’s the story of a man whose ideology begins to conflict with his principles, and whose entire notion of who he is and what he stands for has been torn to shreds as a result of his own empathy and moral awakening. By the end of Season Two, Din Djarin has succeeded in his quest and as a result is left with nearly nothing—no purpose, no culture, no tradition to fall back on and believe in. As such, where his journey goes from here is nearly anyone’s guess.

But I have a sneaking suspicion that however this story ends up blossoming, the seeds will have been planted in The Clone Wars and Rebels.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC