Review: 12 Monkeys

ALSO ON CINELUXE

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Terry Gilliam’s most successful attempt to work within the system, this apocalyptic thriller proved to be prescient—but not just for the expected reasons

by Michael Gaughn

October 3, 2022

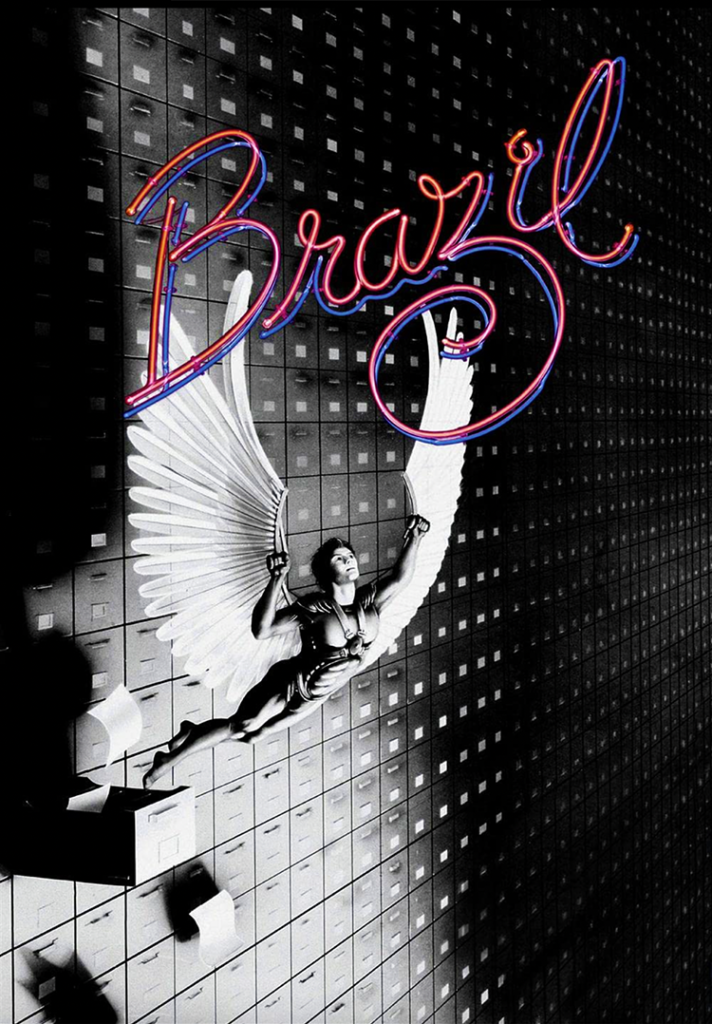

Having had an affirmative experience getting reacquainted with Brazil after the rout of Baron Munchausen, I wanted to do some more digging around to try to figure out if Terry Gilliam was something of a one-hit wonder. I’d watched The Fisher King again a few months ago and, while some of it remains powerful, too much of it feels out of scale with the material. It’s a good movie—far better than most—but can’t even begin to compare with Brazil. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas has its moments but is basically a rambling mess that gets squeezed much too thin. The bottom line seems to be that Gilliam without a solid script is mainly an occasionally compelling diversion.

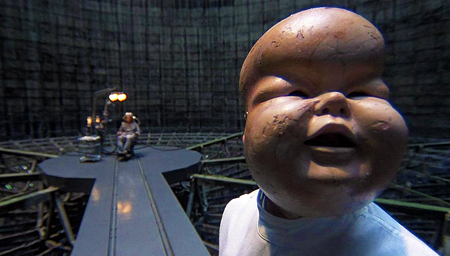

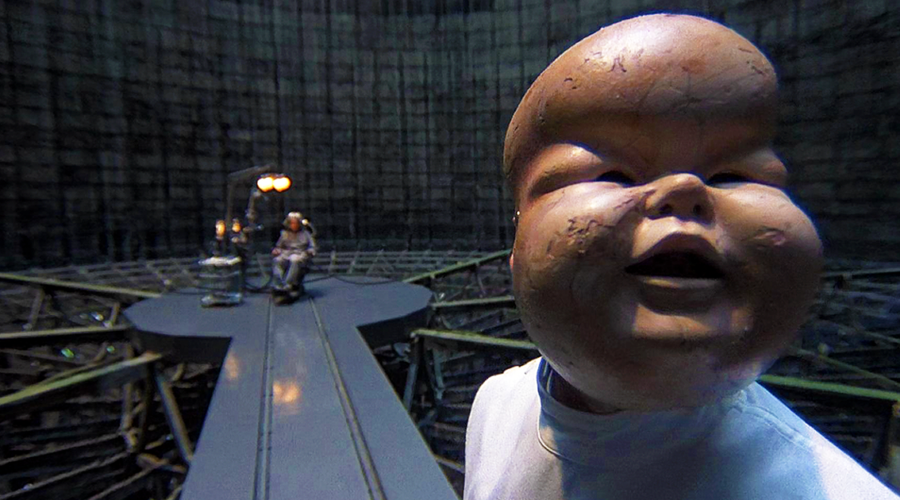

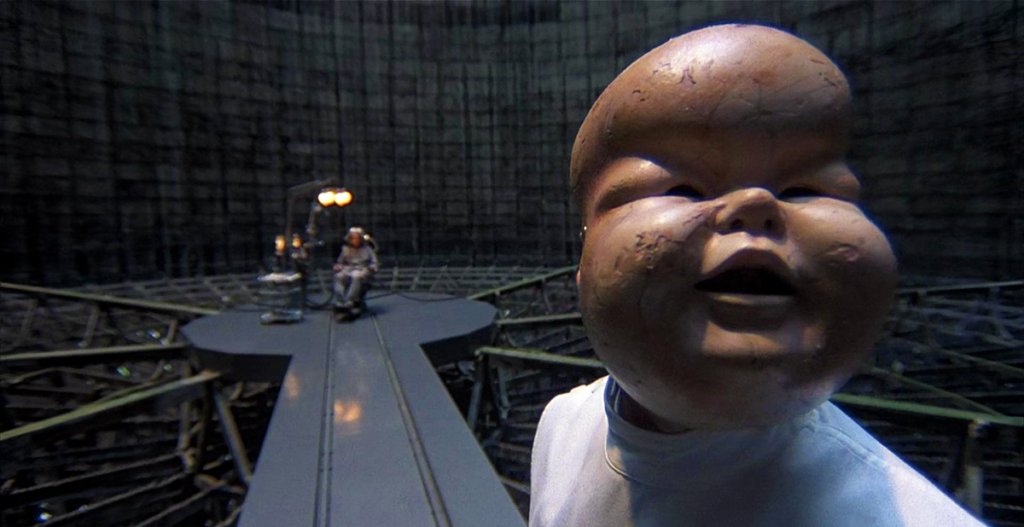

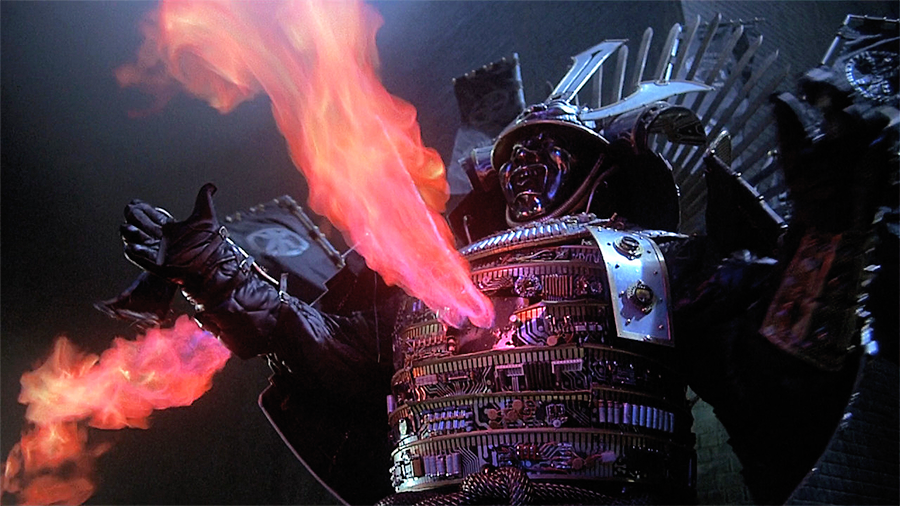

The Peoples’ script for 12 Monkeys is way too full of itself but gets most of the structural stuff right enough to let Gilliam build something pretty substantial atop it. But his greatest achievement here—which definitely isn’t derived from the script—is the tone, the ability to give a presence to the impalpable. 12 Monkeys feels like an elegy—one that manages to be both moving and troubling without being either depressing or sentimental. As soon as we know almost every character we see on the screen is soon going to die, a consistent tenor takes hold that makes everything feel both tenuous and more vivid.

And Gilliam establishes that tone—it can’t really be called a mood—so strongly that even his lapses and indulgences can’t queer it. The Britishisms and silly gags he was able to make work, to some degree, in Fisher King feel alien here and push you damn close to the point of “O, come on.” But the film’s portrayal of the end is so credible that it carries you over the errors in judgment.

And a lot of the credit for that—and I can’t believe I’m writing this given that I’m talking about Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt—goes to the acting. Bruce Willis is always Bruce Willis, or something less than that, but Gilliam gets him to stretch well beyond his persona and, by adeptly molding the individual moments of his performance, succeeds in piecing together a nuanced and forceful whole. Pitt, in probably his only convincing role, takes what can be seen as just goofing and makes it feel like that absurdity, in sum, is the character. Although his Jeffrey Goines is something of a red herring, it was crucial to the film to show that there’s a menacing chaos at the heart of all his acting out.

Why didn’t Madeleine Stowe ever have a career? Her performance, which is the film’s fulcrum and is subtly modulated but in a way that becomes powerful, should have led to her having her pick of standout roles. It could have been a personal thing or an industry thing or just a dearth of good enough parts, but it’s a tremendous mystery, and a huge loss. She brings much needed weight to the the film through her believable pivot from intelligent and perceptive but hopelessly smug to utterly lost and desperate to believe.

Seen as a madcap stylist, a Goldbergian concoctor of cinematic gadgets, Gilliam has never received his due as an actor’s director. But his films, going back to Time Bandits, have been graced by exceptional performances, even when the material didn’t seem substantial enough to hold that kind of weight. 12 Monkeys is driven by the acting, not the style.

My comments about the HD presentation on Prime (as a portal for Starz) are made knowing a 4K remaster was done this year and a new home release could be imminent. Parts of the film are in surprisingly bad shape for something from as recent as 1995, with the quality sometimes varying tremendously from shot to shot, especially near the beginning. While much of the movie holds up well watched on a big screen, those sudden soft or super contrasty moments can be jarring.

As we’ve seen repeatedly, 4K is no panacea—it can even be an older film’s worst enemy. Depending on the elements they had to work with for the remaster, a new release could be a benison or could be uneven as hell. I’d be especially concerned it would accentuate the flaws in the decent enough but definitely now creaky CGI. That said, I’m keen to check out the 4K, if or when it comes.

Allow me to ruminate for a moment on my way out the door.

The intuitiveness of the mass consciousness can be startling. The dire events portrayed in this film, until then just the shouts of lone voices, weren’t even thinkable on the mass level until around 1995. It’s as if we were beginning to prepare ourselves for everything that’s transpired over the past few years, and for the worse to come.

And, as often happens, the surface content of a film—or wave of films—also has a self-reflexive cinematic complement. By getting you to feel the death of the race in a way that gets into your bones, 12 Monkeys gets you to sense the death of emotion in movies as well. It’s hard to pin down exactly but there was a distinct moment when the movies (all entertainment, actually) crossed a rubicon from being grounded in humanity to deriving from a kind of unfeeling viciousness, when creativity devolved into facile cleverness, when it all shifted from grounded in emotion to cruel, abstract exercises in the coldly cerebral.

That moment seems to be right around the time of 12 Monkeys’ release, with the solidifying of the Coens and the rise of Fincher, Jonze, the Andersons (Paul Thomas and Wes), Nolan, and others of their ilk. Their work resonates as long as you can view it with an arm’s-length detachment, don’t invest too much in it emotionally, and don’t bring your full being to bear. In other words, as long as you don’t allow yourself to feel. None of the above-mentioned could have summoned up any of the bittersweet sense of passing that pervades 12 Monkeys because none of them could have sensed it to begin with.

12 Monkeys is the cry of the canary in the coal mine, the voice essential to survival we’ve since opted to drown out with the screeching din of an increasingly brutal culture. Given that we were just capable of hearing that warning at the time the movie came out, I have to wonder if it has any value as anything other than an evening’s amusement now.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC