Review: Creature from the Black Lagoon

review | Creature from the Black Lagoon

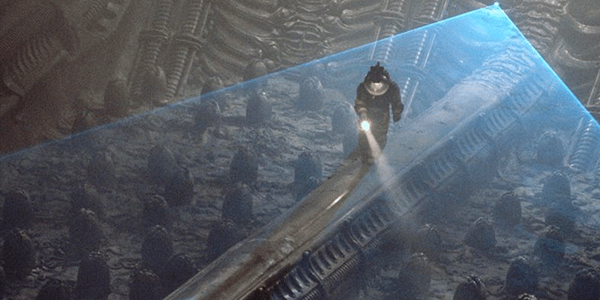

The movie that made guys running around in latex monster suits a thing would seem like a curious choice for a 4K HDR makeover

by Michael Gaughn

November 3, 2022

You can’t lump the work of an entire decade of filmmaking under one umbrella but the movies that best define the ‘50s all exhibit a kind goofy optimism—which is kind of weird given that the culture was grappling with the recent shocks of global war, economic depression, and genocide and with the new threats of nuclear annihilation and ever-lurking Communism. But I guess unbridled prosperity cures all ills. You can feel that almost reckless sanguinity almost everywhere in the era’s movies—in the musicals and comedies, of course, but also in the melodramas (something Douglas Sirk had a field day with), noir (Kiss Me Deadly), and even sci-fi and horror. That odd ebullience is still seductive—which helps explain the continuing appeal of Mid Century Modern. And of what would otherwise be tedious monster movies like Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Universal recently brought out some of its classic horror films, like Creature, The Mummy (1932), Phantom of the Opera (1943), and Bride of Frankenstein, in 4K HDR. My first instinct was to go for Bride of Frankenstein, which remains fascinating, mainly because it shows the monster genre veering into self-parody almost from its inception, but I thought Creature, being more recent, would be a better candidate for HDR. I should have trusted my gut.

This is the kind of film that fascinated me as a kid but became harder to slog through once I developed a sense of how movies are made and what they’re capable of expressing. It’s a necessary skepticism that comes with the loss of innocence—the tradeoff of naive pleasure for insight—but some films can be really tough going once you can see their technical and aesthetic seams are showing.

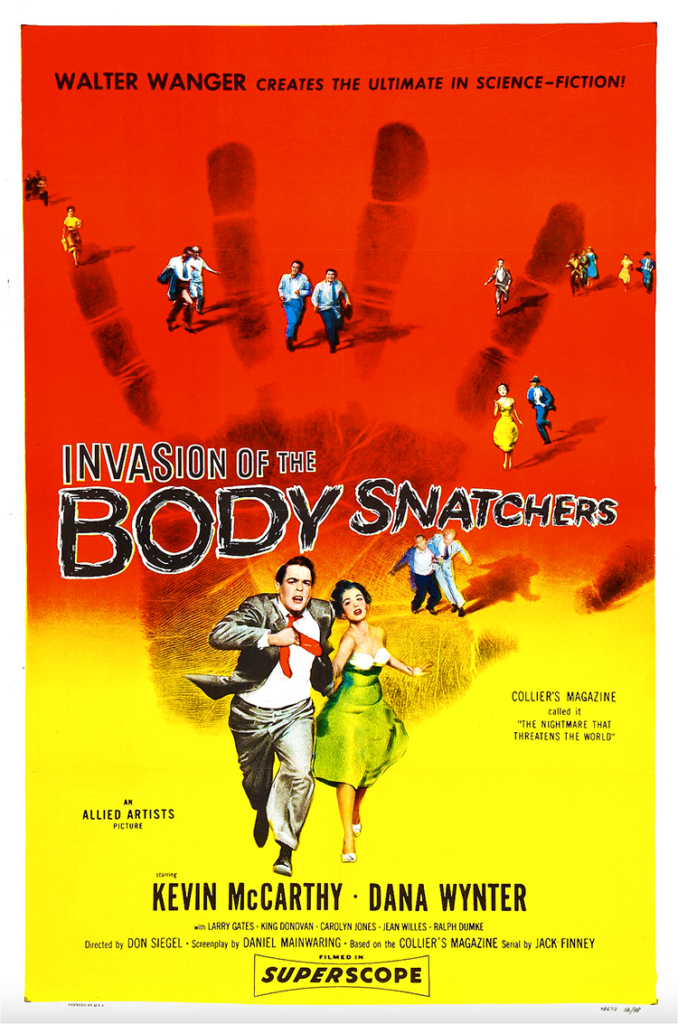

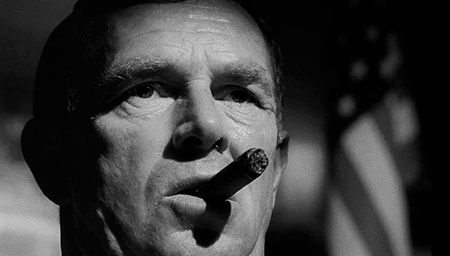

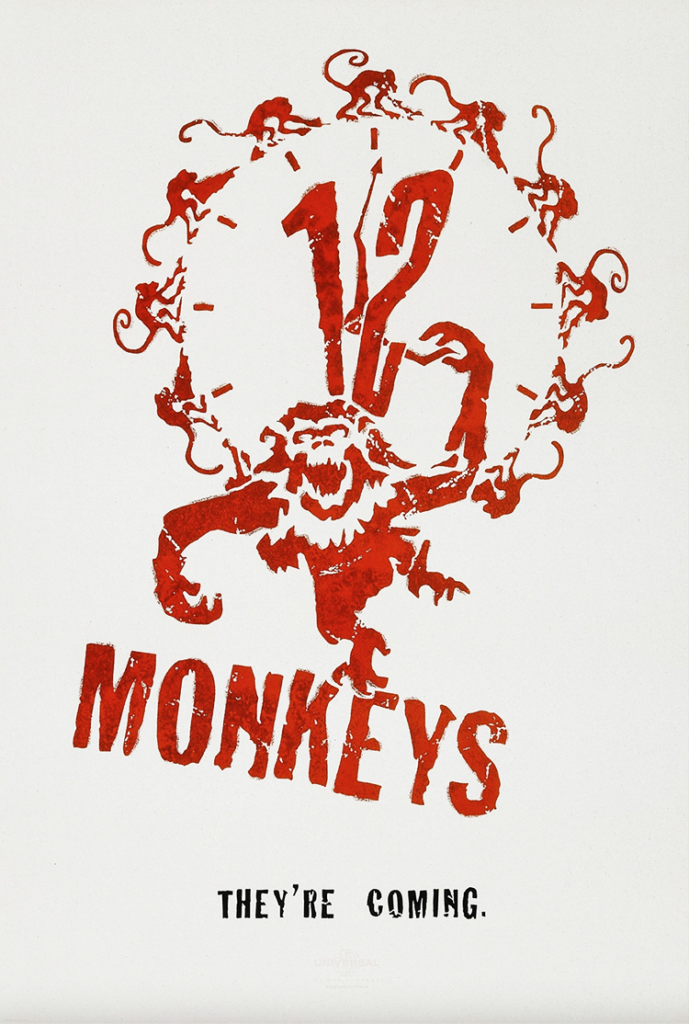

Creature was a cut above the usual monster flick of the day but still far from A-list. The presence of Whit Bissell alone (who last appeared in these pages via Invasion of the Body Snatchers) tells you you’re solidly in the realm of the lucky to have an acting job. That impression is bolstered by the presence of Richard (It Came from Outer Space, Tormented) Carlson, who looked equally out of place in whatever film he was in and was probably one of the least convincing actors to ever have his name above the title. And then there’s the lone female presence, the oddly visaged Julie Adams, who obviously got the role solely on the strength of her breasts.

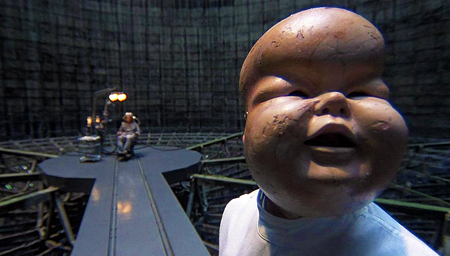

There’s also the defining ‘50s trope of kill what you don’t understand (actually a shade more enlightened than our current paradigm of kill anything that moves), here tempered a little by Carlson’s pleas—until the creature snatches his girl and then all bets are off. And of course the monster starts by polishing off the coolies before working his way up the ethnic pecking order.

The two things that are fair to expect from even a B-level horror movie are some kind of sustained mood and at least a yeoman-like effort to create tension within the set pieces. What Creature has instead is a bunch of alpha males swarming all over the desirable female, a boat stuck in a lagoon, and an iconic latex monster suit—and a both rote and turgid score. You come to dread hearing the monster’s theme more than seeing the monster himself.

But enough with beating up on a defenseless old movie. Let’s discuss the transfer. To sum it up before laying out my case: This is another instance of 4K HDR accentuating all the flaws of a film that wasn’t that well shot to begin with and whose elements have likely deteriorated over time. That’s not to say HDR and black & white can’t be friends—just look at Shadow of a Doubt to see a movie—and the experience of a movie—brought back with all its original impact intact.

But Creature is all over the map visually, with some shots crisp, some so soft they look like VHS (and that is not an exaggeration), some in nicely gradated black & white, some in a muddy wash vaguely resembling sepia. Everything going in and out of dissolves looks like it’s been dipped in acid, and some of the underwater photography is so vague it resembles a 16mm art film—Maya Deren Meets the Creature.

Given that, it seems almost unfair to bring the movie out this way. It’s unfortunately becoming common with UHD releases of older titles that you have to look past the compromised footage while waiting for the good shots to show up, which isn’t a very pleasant way to watch a film. Of course, as many classics as possible should be re-released in 4K—we’re all better off being able to see 2001, Singin’ in the Rain, Vertigo, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly in that format. But here—and I admittedly haven’t yet seen any of the other titles Universal has released in its horror bundle—I have to wonder if this wasn’t more about “let’s get them to buy the title yet one more time” than anything else.

It was literally hard to see what the extended dynamic range brought to the presentation. The flashbulb whites made the “In The Beginning . . .” shots of primordial creation look blown out and the flames streaming off the creature look animated (they aren’t). The flame in the lamp that hangs over poor Whit Bissell right before he’s attacked was so vivid it looked matted in. And you’d at least expect the lagoon in a movie with “Black Lagoon” in the title to look blacker. It didn’t.

I’m not sure what fans of the film will make of this presentation. Maybe, having looked past its visual flaws in the earlier incarnations they’ll be willing to forgive them being heavily underscored here. My take is that drawing too much attention to the technical lapses makes you that much more aware of everything else that’s wrong. But you can’t expect a well-intended but inept ‘50s creature-on-the-loose throwaway to look like Citizen Kane.

Sorry—bad example.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC