Noah Kaplan–Bringing Entertainment & Design Together Again, Pt. 4

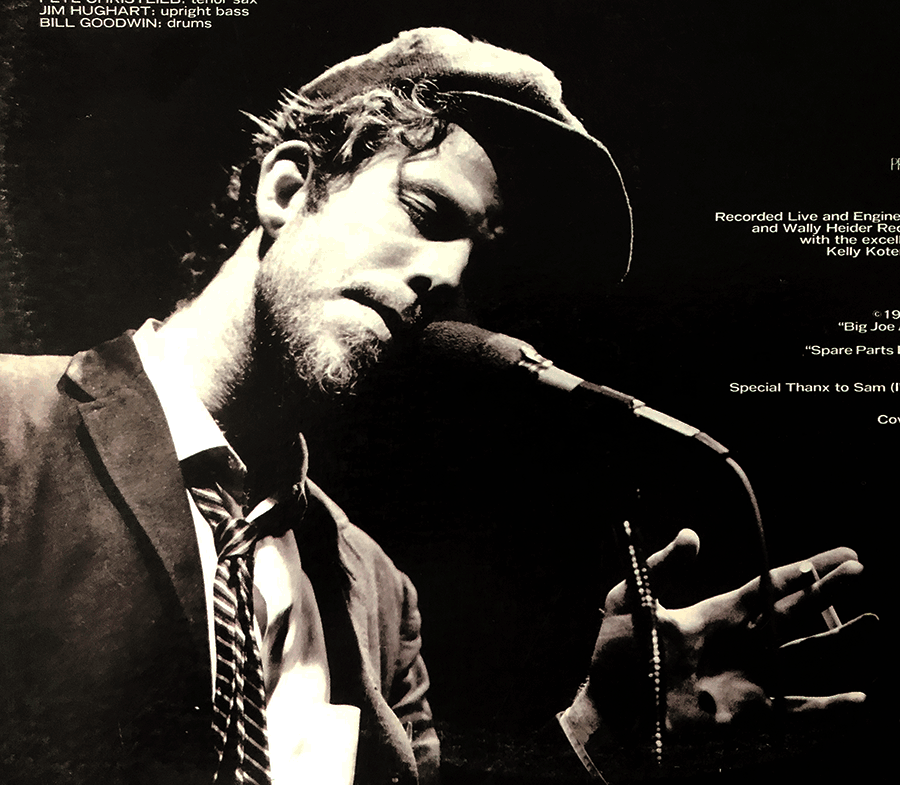

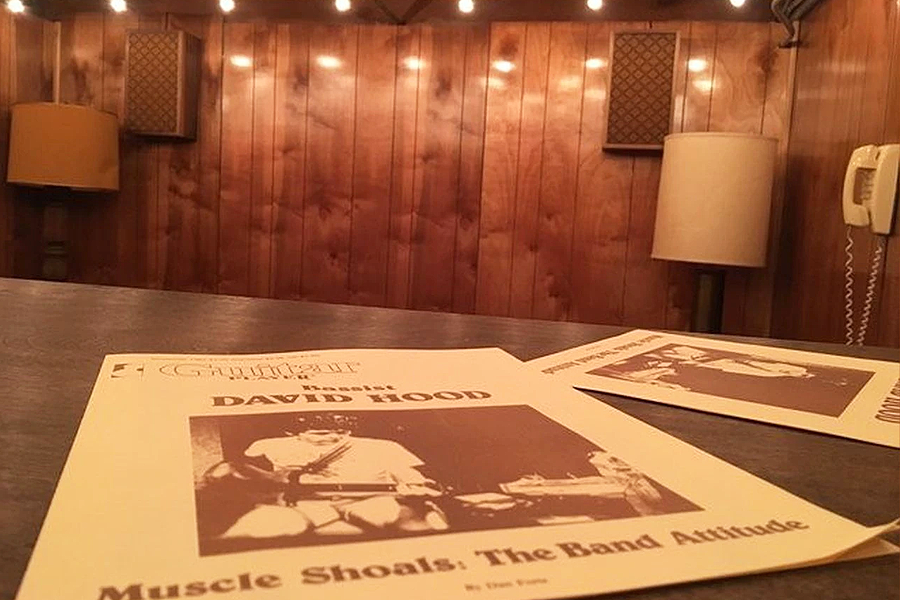

capturing the spirit of the ’70s, without the kitsch, at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio

a custom python-skin design for Wu-Tang Clan’s Raekwon “The Chef”

“We’ve got to show that technology companies today are as interested in how things look, how they’re sourced, how they make you feel,

and how they’re end-of-lifed”

The interview concludes with a glimpse of a time to come when entertainment tech will once again fully embrace innovative design

April 21, 2022

As we wrap things up, Leon Speakers‘ Noah Kaplan neatly brings things full circle, weaving together all the threads he laid out in the previous three installments. The focus here is primarily on the future—not just of Leon but of home entertainment in general as it continues to spread out, in increasingly sophisticated forms, throughout the home, and thanks to more nuanced and responsive technology and design, evolves from an often awkward add-on to an integral and stylish part of the domestic environment.

—M.G.

You mentioned that the mandate with Muscle Shoals was do to a ‘70s-based design. That era’s kind of dangerous because no matter how you approach it, it can quickly descend into kitsch. How do you avoid that when you’re approaching a style like that or something similar?

That’s where subtlety plays in. We always call it a drip. We don’t ever want to go into full IV mode. I’m super conscious of that when we’re designing. Our designers are working on stuff usually five to ten years, so we’re always designing for ten years on. We have some super crazy concepts, but we’re making sure it’s a very slow progression. So first let’s add new materials, then a color choice or a fabric choice. And then let’s add design options, like trim options. But in most cases still, especially in American design, we’re working with very subtle and simple styles.

Now, we do make sound sculptures that are full-scale expressions of ourselves. And the customer who wants a sound sculpture is somebody who loves art, so they want that piece to pop. Another customer might want a product that makes them feel something at the same time that it fits the right aesthetic of their home design, but they also don’t want it to yell at them. So it’s a tightrope still, giving people what they want while also pushing the boundaries just a little. Because you always know who the customers are who want you to totally trash boundaries and just create. But that’s three or four times a year compared to the ten thousand times a year when we create for the people who need stuff everyday.

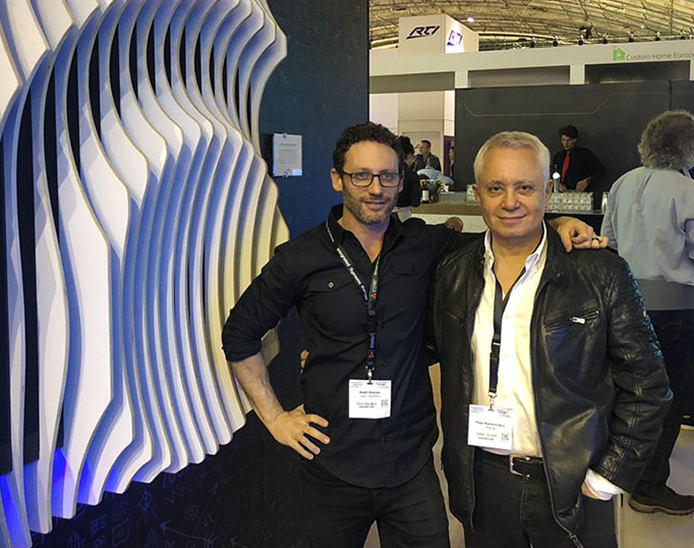

Theo Kalomirakis always reminds me that during the pinnacle of his career, in the ‘90s, he had client after client who just wanted to play. And if he could sympathetically get them on the same wavelength with him, that they were going to be creative and were going to play, that’s when he did his best work. By the 2000s, those people started to go away. Most of his clients just wanted glorified screening rooms and it wasn’t creative anymore.

I like those words “sympathetic” and “play”—two of the things we try to find all the time now. If I get to get on the phone with a customer, which is rare, look out. We’re goin’ there. Like when we just did that thing for Raekwon, who wanted that python skin and so I’m finding that python skin. That’s what we want. That’s a desire. I had a conversation with a customer this week who’s moving to an amazing place in LA but has no idea what to put in there. She showed me with her phone, and she had not one piece of art. And so I’m, like, you wanna play?

So, like Theo, I’m always looking for that one person who wants to go and dig deep. Because I think intrinsically all people do. We’re ready to reconnect with a little bit more of our soul; we want to find something that makes us feel good. And what I really love about what Theo does—he’s creating an escape room, a playhouse. Sometimes we get too serious about stuff. It’s not that serious, and you should be allowed to make mistakes. You should be allowed to build something and then not even like it. We’ve built whole apartments with customers and, not because of us, they didn’t like it when it was done. And, you know what? No worries. Let’s find what you do like.

I feel like we have such a creative industry. All the people we work with are super creatives, and willing and able to start the conversation of, “Hey, I know that’s what you think you might want, but did you know?” Because a lot of people don’t have awareness. And here’s the scary thing: If I asked a hundred people to name five artists, I don’t think they could. Some people might say Van Gogh, but how about one that’s alive? If I asked them to name one architect, I’m not sure they would know. I don’t judge people for that. I just know there’s so much more depth out there than that. So like Theo, I’m always want to play with those thoughts as a way to find someone’s soul. And that’s a really deep, interesting way to design and build stuff for people. That’s what’s cool about architecture and art and design to me.

Let’s talk about the next 3 to 5 years. How do see things playing out, and how would you like to see things play out? What do you think are the trends?

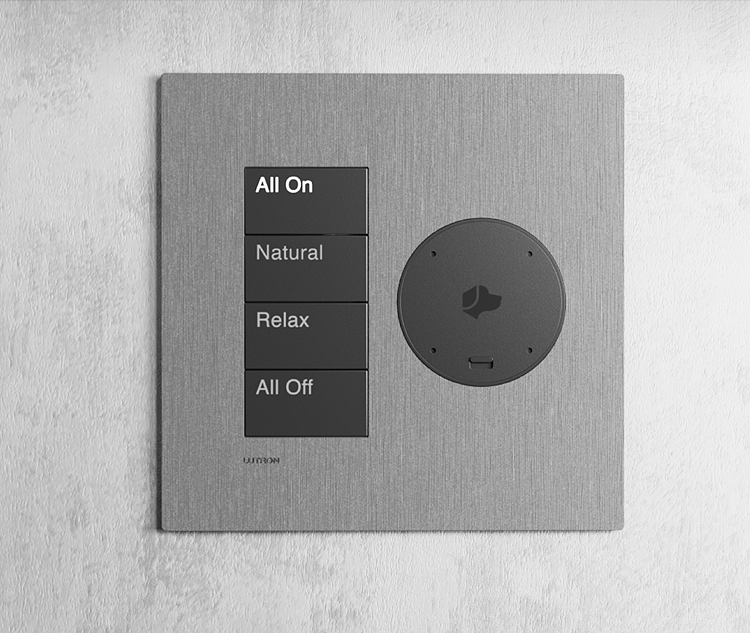

I think the trend actually is going to be in learning—learning like how different trades interact with each other, because as technology infiltrates everything, we’re actually shifting really deeply into IT. And you hear a lot about wellness—about Kelvin lighting and how it affects your health and your mood. That’s a great trend. I want to work in an industry that makes you feel better, not worse. And so I love these multidisciplinary things happening.

I was on a call the other day with an integrator who was saying the usual thing of, “We’re always called in last, so we’ve got to train designers and architects to bring us in early.” And I said, “What have we got to train you on?” We have to start learning more about the terminology of architecture and design, the history of design. Through that, we’ll get to this next zone where design and technology are finally remarried. We’ve got to show that technology companies today are as interested in how things look, how they’re sourced, how they make you feel, and how they’re end-of-lifed. We talk often enough about how this can be a sustainable practice. It doesn’t have to be all about growth and this maniacal big, bigger, bigger.

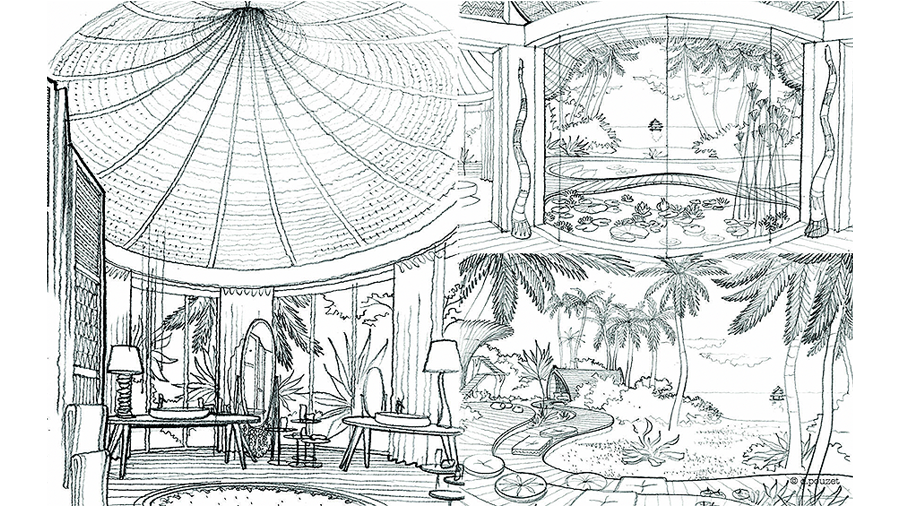

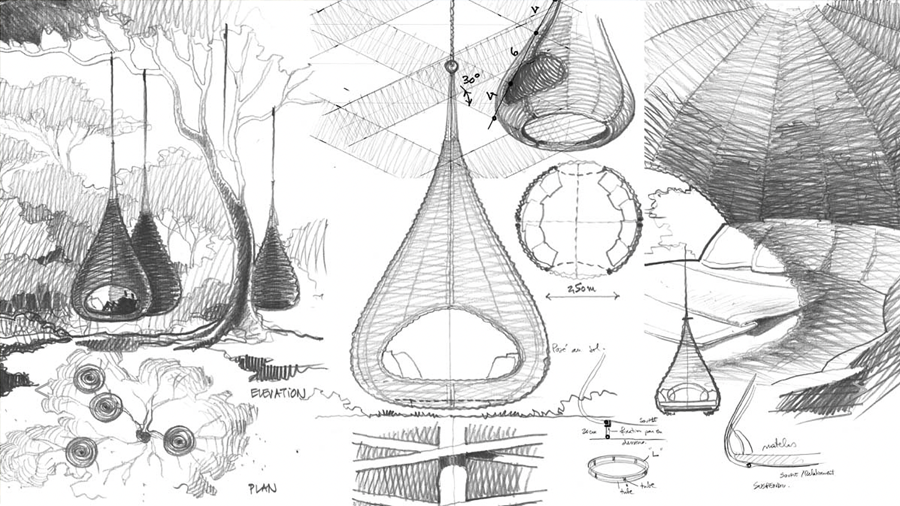

The future will be more about the wellness of an overall space, which is super interesting to me. So I’m working closely with an architect out of Paris, Daniel Pouzet, who’s one of my favorite designers—a very naturalistic designer. And he’s really thinking about what is going to make the client’s life better through design. So I became obsessed with the idea of, if you see an object that makes sense to

Kaplan introduces a Leon Ente SoundTile speaker system created in collaboration with artist Mike Han

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

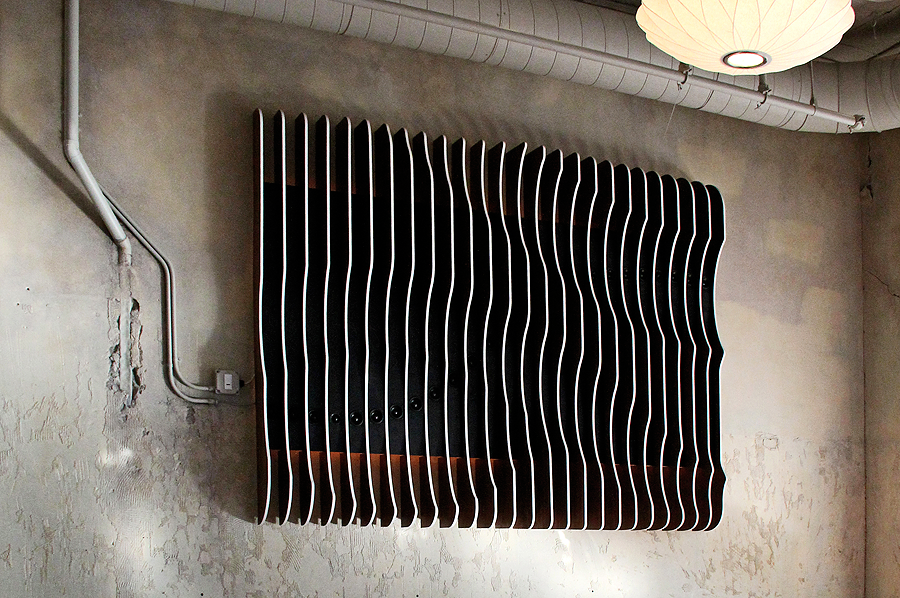

this sound sculpture, custom designed for an Ann Arbor, Michigan cafe, won a BORN award for its combination of functionality and aesthetics

Kaplan with Theo Kalomirakis

related article

a sampling of Daniel Pouzet left | the Villas at the Nay Palad Hideaway in the Philippines right | the Nest Rest and the Swing Rest

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

you and resonates with you and makes you feel better, it’s going to add to your overall wellness, it’s going to relieve your stress. We can’t overlook how much stress we’ve all been under. And everyone’s spending so much time at home. That trend’s going to continue.

So what are we going to put our energy into? Are we just going to keep buying commodity things off Amazon? Probably for a few more years, but eventually we’re going to let all that stuff go and think about those few things we actually need or desire. So I’m thinking about everything from how the digital landscape is changing, about how we’re going to present NFTs and new art forms all the way to simple things like what materials can we build with that can be additively manufactured—printed on demand. We’re meeting with a company in Ireland to help us with additive manufacturing because I want to create a sustainable business that doesn’t have a giant environmental footprint.

The trend that makes me nervous is when I see conglomeration, which can hurt the spirit of design, because something that was super important to a founder can become unimportant to another group of people. So I hope there’s a move to independent businesses, creative companies flourishing, small, new entrepreneurs coming up—the next person who can inspire us to repropagate ourselves. But in terms of any trend toward one thing, we all know that the trend is moving in the direction of design.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC