The Godfather: The Greatest, or Just Great?

related reviews

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Coppola’s breakout film continues to ascend in the pantheon for reasons that don’t have much to do with the worth of the classic he created

by Michael Gaughn

April 5, 2022

The Godfather keeps creeping up the list of Greatest American Movies, and, with its 50th anniversary upon us, the time seems ripe for a consensus to form to anoint it the best. It’s not. It might not even belong in the Top Ten—unless you subscribe to the movie-by-blender school of filmmaking. It’s an undeniably great effort, but the reasons it still resonates have very little to do with its worth as a film—thus this column.

In the early ‘70s, American society was still numb from the chaos of the ‘60s. Hollywood had tried, and failed, to assimilate the Counterculture, and did an even worse job of repackaging things like Vietnam, civil rights, and the almost complete collapse of governmental authority. (Forget that it didn’t even sense the seismic tech revolution rumbling in its midst.) Beyond lost, the movie industry looked backward, leaping completely over the turmoil—but also considerable ferment—of the previous 15 years.

The Godfather was really the first manifestation of that that really meant anything, the first stab at retro that resonated on the big-box-office scale. The Long Goodbye came the next year, but closed as soon as it opened. Chinatown appeared the year after that and did well with audiences and critics, but Polanski was far more wary of the Romanticism Coppola aggressively embraced.

Every one of those films represented a probe, sent forth to see what spin on the safe and understood (i.e., predigested) past the traumatized public might be willing to fork over big dollars for.

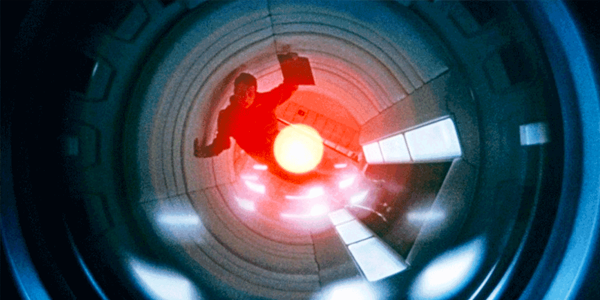

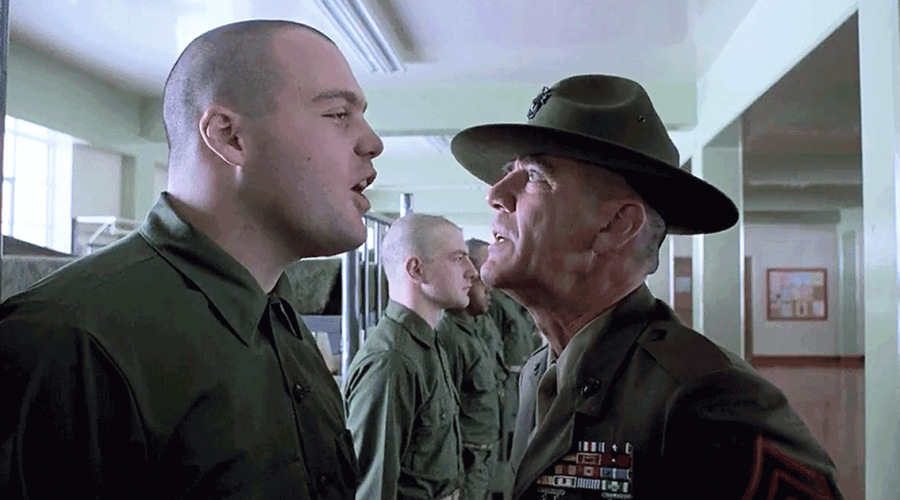

The traditional argument is that The Godfather was somehow transformative because of the brutality of its violence. It wasn’t. It came five years after Bonnie and Clyde, three after The Wild Bunch, and a year after both A Clockwork Orange and Straw Dogs. It had nothing new to teach us there. What was transformative was its wedding of graphic mayhem with the snug glow of the Studio Era. Making violent death not just palatable but heartwarming for the masses is The Godfather’s masterstroke, laying the groundwork for the emergence of late ‘70s blockbuster- and franchise-driven cinema, which continues to plague us today.

But even that doesn’t explain the film’s continuing appeal. The Godfather represents possibly the greatest pivot in the history of American movies, and continues to rise in esteem year after year, because it is the first blockbuster that was, to its core, cynical. That cynicism became a virus that has infected practically every film made in its wake. No other piece of filmmaking has had a greater influence on changing the tone of the movies, on making dark not just an aesthetic choice but (hopefully not permanently) the coin of the realm.

The Godfather continues to rise in popularity and reputation not based on its merits as a movie but because it embodies the beginnings of, and allows us to reaffirm our faith in, the mass surrender of hope that spawned the Reagan Era and the near-constant churn of too-big-to-fail cinematic exercises in nihilism and oppression we continue to respond to with, “Don’t take it too seriously—it’s just a movie.”

Accepted wisdom sees Coppola and Lucas as developing on parallel paths and then radically diverging. But viewed through the lens offered here, Star Wars becomes not an alternative to Coppola’s work but its natural and inevitable extension.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC