The Greatest Filmmaker You’ve Never Heard Of

The Greatest

Filmmaker

You’ve Never

Heard Of

Radical documentarian Adam Curtis has had a platform on the BBC for 40 years, yet nobody seems to know his name

by Michael Gaughn

related content

March 6, 2023

How can somebody be making large-scale documentaries about high-profile subjects on the BBC for four decades and still be treated as essentially an underground filmmaker? I keep asking intelligent, perceptive, otherwise attuned people if they’ve aware of Adam Curtis, eager to stumble across a single other being who shares my wonder at what he’s accomplished, yet always come up empty. After a while, it creates a Carnival of Souls kind of alienation, as if Curtis and his films exist in some parallel world where he just can’t be perceived.

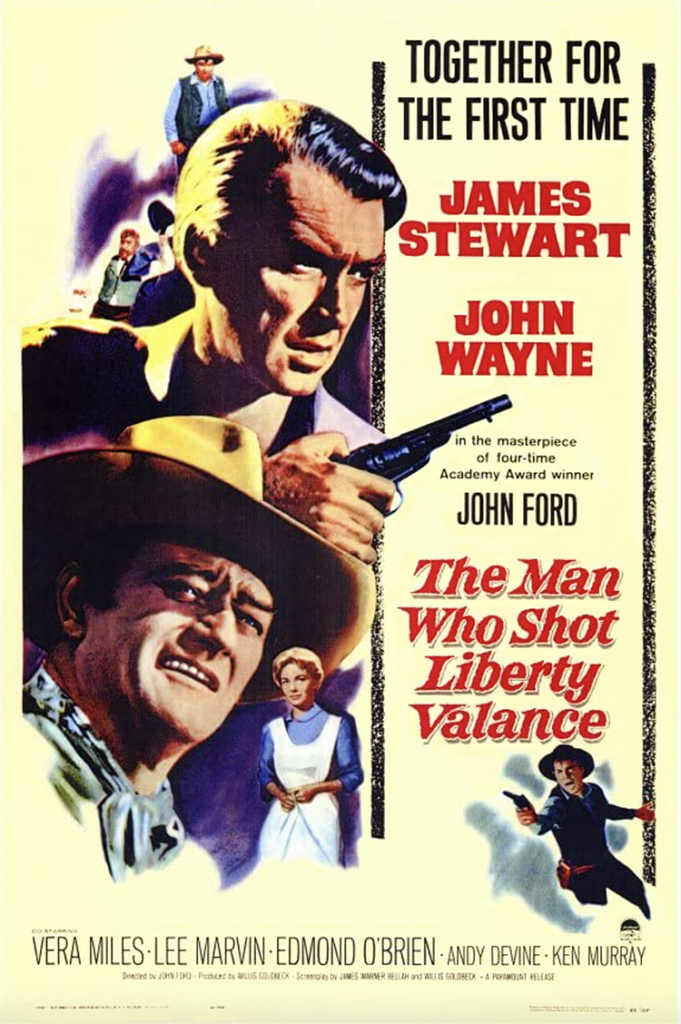

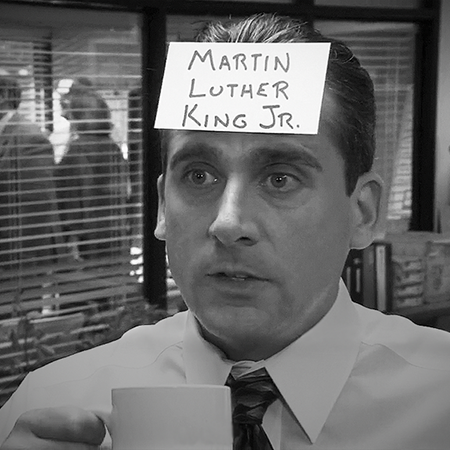

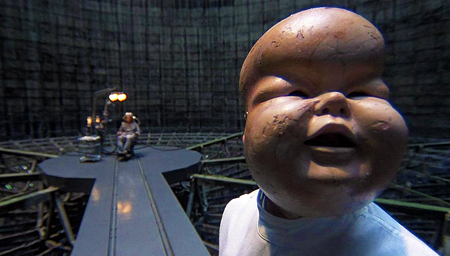

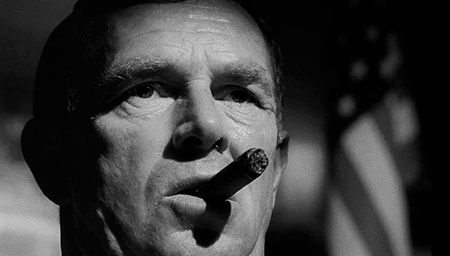

Yes, he’s a deeply radical, subversive filmmaker—but he’s on the BBC, for chrissakes, so it’s not like he’s shouting on street corners or plotting in some dank basement. It’s true, though, that he just doesn’t fit the BBC mold. Rarely using originally shoot footage, he instead plunders the network’s archives for evocative images and moments that often don’t literally illustrate his points but instead act in a kind of frequently ironic counterpoint. And the footage is often low-res and all over the map quality-wise, sometimes wandering into sub-VHS territory. There’s not a dime wasted on slick graphics, silly animation, or lame reenactments, the final product instead feeling handmade, like you’re looking at a rough cut instead of something meant for release.

Maybe most damning of all on a mass-acceptance level, you have to pay attention during every second of a Curtis documentary for the experience to mean anything at all. There’s no Felix the Cat redundancy between what is said and what is shown, and often the deepest meaning lies in an unstable zone somewhere between those two points; no Mickey Mousing of music and visuals, the cues and interludes often leaving you wondering what the music has to do with what you’re watching, and yet the pairings always feel eerily right.

He’s not pedantic, never telling you what to think or feel but instead laying out threads and urging you to follow them yourself, to make your own connections. He offers suggestiveness, not certainty—which of course couldn’t be more antithetical to the spirit of the age, where everything has to be an unambiguous guarantee, a trivial variation of whatever went before so the audience is never in any meaningful way engaged or challenged but instead left undisturbed in its slumber. But he’s never sloppy about developing his themes—there’s always a rigor behind what can often just seem like a bunch of “what if?” riffing.

The most ironic thing might be that, although he doesn’t follow any of the traditional rules of documentary filmmaking and doesn’t indulge in the kind of fawning Documentary Lite glibness that pockmarks Netflix like acne, his films are hugely entertaining, often laugh-out-loud funny, in a mordant, puckish way; moving without being sentimental; disturbing without being gratuitous. (The funniest bit might be Acoustic Kitty, a house cat the CIA spent 25 million dollars reengineering to turn into a surveillance device, only to see it get run over by a cab while crossing the street on the way to its first assignment.)

What’s probably most powerful is that Curtis’s films are documentary as art—or, more aptly, art in the form (or guise) of documentaries. His ability to create evocative, often unsettling, moods, a self-consistent and expressive experience that can stand on its own separate from the narration or even the putative themes, is astonishing, and ultimately gratifying. To use a word most people approach with distaste, his films are, in their gritty way, poetic, in a medium—the TV documentary—not exactly known for its poetry.

It’s symptomatic of his work that I can’t give you a single emphatic reason for checking it out. It’s the whole package or it’s nothing. But that package is endlessly intriguing and provocative, constantly wary of the official cultural narratives while never succumbing to the simplistic certainty that mars most radical work. It doesn’t pretend to have a definitive explanation for the unholy mess of the contemporary world but does offer a way of thinking—and feeling—it through. You won’t find it in any way reassuring but, if you’re open to the experience, can find yourself profoundly stirred without feeling manipulated. Curtis is bracing, not soothing, a way to be focused, made aware, not seduced.

And what does all this have to do with the modern tricked-out home theater? On a performance level, not much—on a demo-material level, nothing at all. It comes down to whether you have a theater because you want a machine for producing extreme sensations—a kind of shock generator—or because you love movies. Those two poles are becoming more and more antithetical, like split pieces of matter hurtling off into divergent sectors of the void. But if you prefer exploring the depths to skating on the surface, being engaged to being diverted, stimulated to being abused, Curtis provides a badly needed alternative to shock & awe cinema.

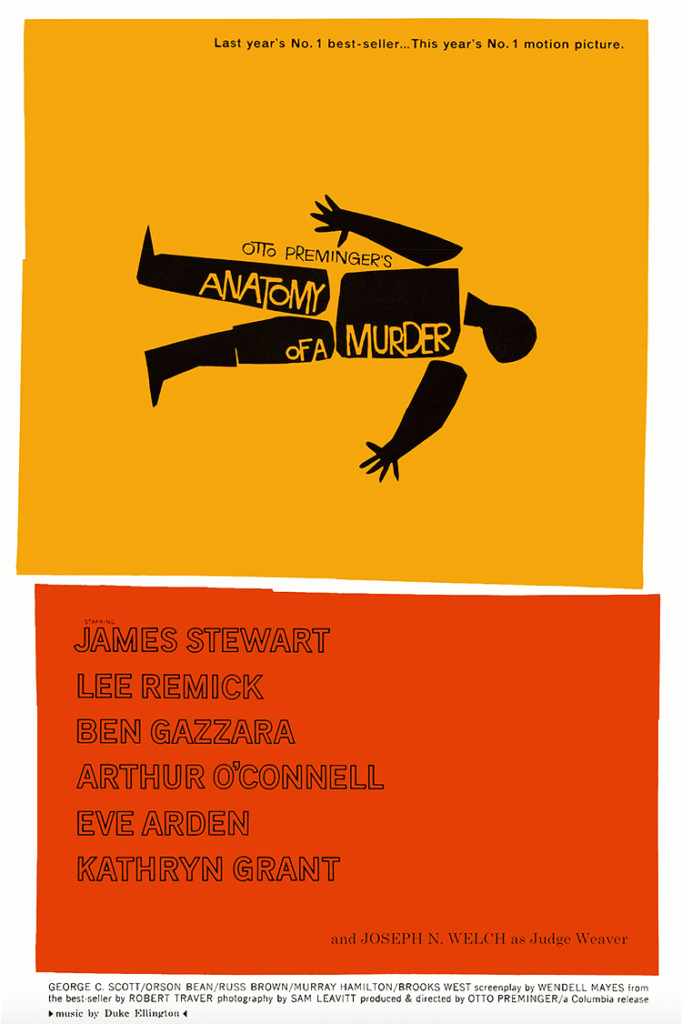

He never underlines it, and it just arises naturally from his work, but his films are a potent reminder of what defines the art of the movies, what lies (or should lie) at their heart. There are no stars, no sets, no exotic locations, no sumptuous cinematography, no dehumanizing special effects, no extravagance at all. Actually, it’s all about the editing—which might be his most subversive move, because it reaffirms that anyone can create cinema—as long as they have some substance to their self and something worth saying.

I’ve barely said anything at all about Curtis, and have unfortunately had to leave most of what’s best about his work unsaid. Unlikely to ever appeal to more than a subset of the film-going public, he seems destined to remain a cult figure. But where “cult” usually means half-baked or trivial, that’s not him. Curtis is must-see for anyone who’s a fan of movies and not just of movie-watching.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC

Streaming Curtis

As with almost all content online, Curtis’s films come and go apparently at whim, and since many of them are multi-part, you can find yourself, as I did with Can’t Get You Out of My Head, having to go to six different sites to watch the installments. Curtis’s situation is more Whack A Mole than most, with All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace and HyperNormalisation available for streaming on Amazon but with none of his other titles in sight. You can see The Power of Nightmares and some of his other work on the BBC’s iPlayer—but only if you’re in Britain. Some of his films have made it to DVD, but don’t tend to be available anymore. I haven’t come across any Blu-ray alternatives. The links below were live at the time of publication. Who knows if that will still be true even a few days from now.

All Watched Over by Machines of

Loving Grace, Pt. 1

The Century of the Self, Pt. 1

The Power of Nightmares, Pt. 1

Hypernormalisation

Can’t Get You Out of My Head, Pt. 1

TraumaZone, Pt. 1