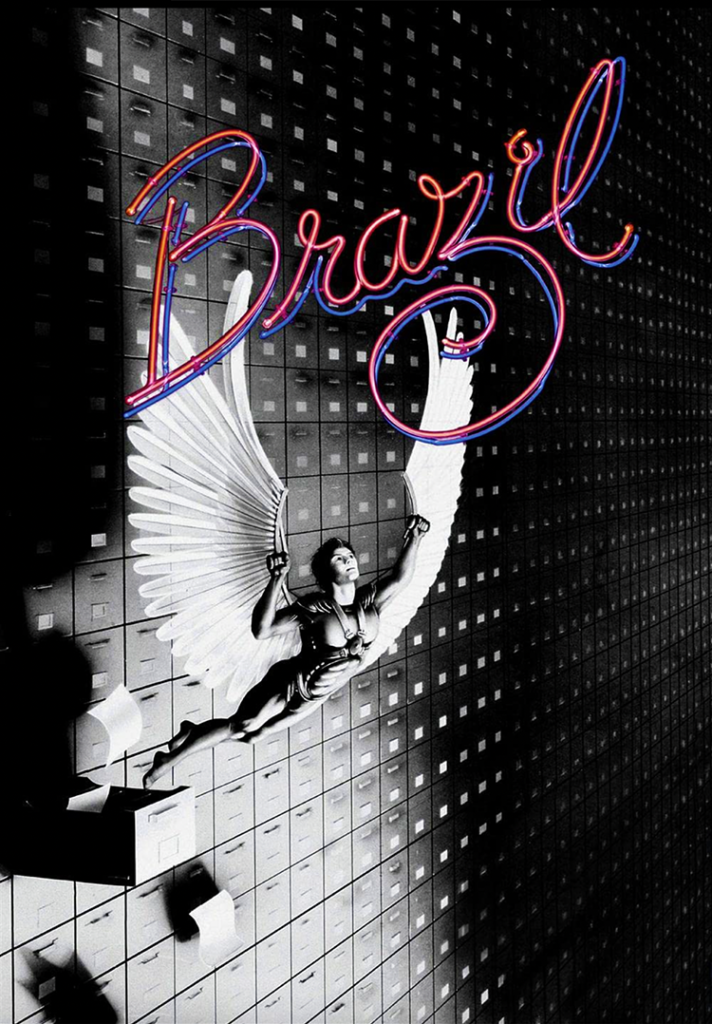

Review: Vicky Cristina Barcelona

review | Vicky Cristina Barcelona

Diving into late-period Woody Allen is always a gamble but this lively Johansson/Bardem/Cruz vehicle remains a pretty sure bet

by Michael Gaughn

September 26, 2022

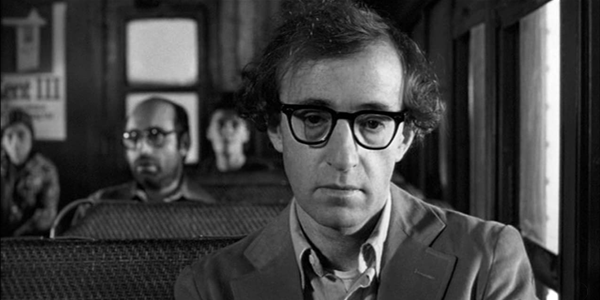

It’s not exactly news that the quality of Woody Allen’s work became incredibly uneven once he emerged from his succession of mid-period classics like Annie Hall, Manhattan, and Stardust Memories. For every Purple Rose of Cairo or Zelig there was a Shadows and Fog; for every Husbands and Wives, an Alice. And it only got more erratic as time went on, having to slog through films like Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Hollywood Ending, and Whatever Works to be able to pluck a Blue Jasmine from the heap.

Not having seen Vicky Cristina Barcelona in a while and not sure what my impression was of it at the time, I was surprised by how strong it is—much more so than expected. More uneven than it needs to be, it’s still consistently engaging. It’s probably Allen’s loosest, most fluid and energetic film. And it still serves as viewer bait for Scarlett Johansson fans, dating from the era when she was allowed to do legitimate roles, before she succumbed to just being a prepackaged marketing commodity.

VCB is Allen’s second-best late-period work after Blue Jasmine. (This will seem incredible to some but I’d put Café Society at No. 3.) Allen was so confident in his skill as a filmmaker by this point that he could just resonate with his material, knowing he’d find some deft and distinctive way to express it. Even at the early peak of his powers he was utterly incapable of making a film like this one, which makes his mid-period triumphs feel constipated by comparison. (To be fair, though, films like Vicky Cristina and Blue Jasmine just don’t have the repeat appeal of those earlier efforts.)

Allen takes a novelistic—or at least short-storyish—approach to the film—something he’s also done in movies like Manhattan and Café Society. But with Vicky Cristina he was so sure of himself that he could be far more improvisational without fear it would unravel in the editing, taking the literary and playing it off the cinematic and somehow getting them to coexist without having it feel like a forced marriage.

The dabs and strokes and feints of the opening, where he sets the action in motion by making a series of suggestions—snatches of dialogue, telling images, evocative sounds, avoiding traditional linearity because he knows films always move forward so a story will arise no matter what—is bravura but completely on point and without being showy. As the film proceeds and Allen further plays around with these ideas, it’s as if the cinematic knows the literary is just there to lay the foundation for moments that are purely about an image, a movement, a sound, a dissolve, a cut, sometimes highlighting just one element, sometimes mixing and matching the emphases. The point, I suspect, is to keep any one character from being dominant and instead keep the focus on the shifting relationships between the characters and on the tentativeness of fleeting emotions.

Vicky Cristina Barcelona is what Sweet and Lowdown should have been but Allen hadn’t yet broken far enough free of his mid-period technique to pull something like that off. It’s a serious mistake—one often committed—to try to attribute what’s best about Allen’s work to his cinematographer of the moment—here, Javier Aguirresarobe, whose images are undeniably both striking and restrained without indulging in romantic clichés—in other words, apt. Instead of taking the obvious approach, VCB makes place—the location, the geographic-cum-cultural-cum-psychological locus—the spring of the romance, and the mise en scène and montage are just extensions—expressions—of it. No further emphasis is needed.

But this all arose from the efforts of both Allen and Aguirresarobe, not because Allen gave his DP free rein. Yes, he’s worked with masters like Willis, DiPalma, Nykvist, and (unfortunately) Storaro, but you’d have to be blind not to see that, no matter how strong the cinematographer’s style or big his personality, Allen has always been able to put it in the service of his material and that there’s a consistent look and feel to his movies no matter who’s manning the camera.

The material here is so fertile that it’s not seriously hampered by the mixed bag of the acting. Strongest is Javier Bardem. I’ve never been a fan, but Allen gives him a lot of room to run with his character, and Bardem takes advantage of every inch of it. Rebecca Hall’s mannered kvetching, and resemblance to a Modigliani, can get annoying, especially early on, but isn’t a dealbreaker and actually helps bolster the film’s payoff. Penelope Cruz comes across as a tad overwrought, sometimes hitting the mark, often flailing to define her character. Johansson is more a presence than an actor, of course, a walking encyclopedia of knowing looks who knows how to smolder her way through a scene but rarely helps to elevate the ensemble.

But, again, VCB is less about individuals than the treacherously unstable ground of relationships, territory Allen captures incisively, and with surprisingly little sentiment. He doesn’t get enough credit for being the first American filmmaker to figure out how to show sex on screen in a natural, convincing, non-gratuitous way. His renderings of carnal encounters are so effortless we don’t realize how brilliant they are, even with more than a century of awkward, overweening, giggly, grotesque counterexamples to draw on.

Because of the whole evanescence of emotion thing, this film really didn’t need a traditional plot, and things get messy and awkward whenever one decides to rear its head. Needing something resembling an ending, Allen introduces some small-arms fire into the proceedings—but he’s always sucked at gunplay. The shotgun dispatching of Johansson in Match Point is one of the most inept, implausible, and unconvincing murders in all of cinema. Here, Cruz firing off rounds in the general direction of Bardem and Hall is a huge false note, a contrivance that sticks out as egregiously as it does because so much of what precedes it is so well done. Somehow, this misstep doesn’t damage the overall impact of the film, partly because Allen redeems himself a few moments later with a lingering silent closeup of Hall who—again, subtly—looks convincingly like a changed person.

I can’t abide lazy, unimaginative reviewers who write the same review over and over, just plugging in some new nouns each time (without varying the adjectives) as if every movie is just like every other and reviewing them is a robotic form of Mad Libs. That said, there’s not a lot new to say about Amazon’s presentation of relatively recent films, which tends to range from acceptable to occasionally extraordinary. This one falls somewhere in the middle, not harming Aguirresarobe’s work but not fully honoring it either. That will take a 4K transfer—but because this is an Allen film and there’s no justice in this world, I’m not holding my breath.

The warmth of almost every frame is almost there. The subtly muted tones—a look digital has yet to achieve—are pleasing but not as beguiling as they should be. On the other hand, the soft-focus tracking shot of massive sparklers going off in front of a church—the kind of thing streaming consistently bungled just a couple of years ago—is surprisingly solid and clean.

The phrase “a Woody Allen movie for people who don’t like Woody Allen movies” has always made me cringe—for a lot of reasons, but mainly because the two films most often mentioned in association with it—Midnight in Paris and Match Point—are among his worst. I guess it could be applied fruitfully, though, to Vicky Cristina Barcelona, which definitely stands on its own. But to not have the context of the best of the rest of Allen’s body of work and to not know how it both syncs up with and veers away from all that is to be deprived of one of the richest parts of the experience.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Not quite capturing the film’s overall warmth or subtly muted tones, Amazon’s presentation doesn’t harm Javier Aguirresarobe’s work but doesn’t fully honor it either

SOUND | It’s a Woody Allen movie, for chrissakes. You can clearly hear people talking and the music cues sound fine—in stereo.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC