Review: Contempt

review | Contempt

Only Jean-Luc Godard could create an epic that’s all about intimacy

by Michael Gaughn

June 12, 2022

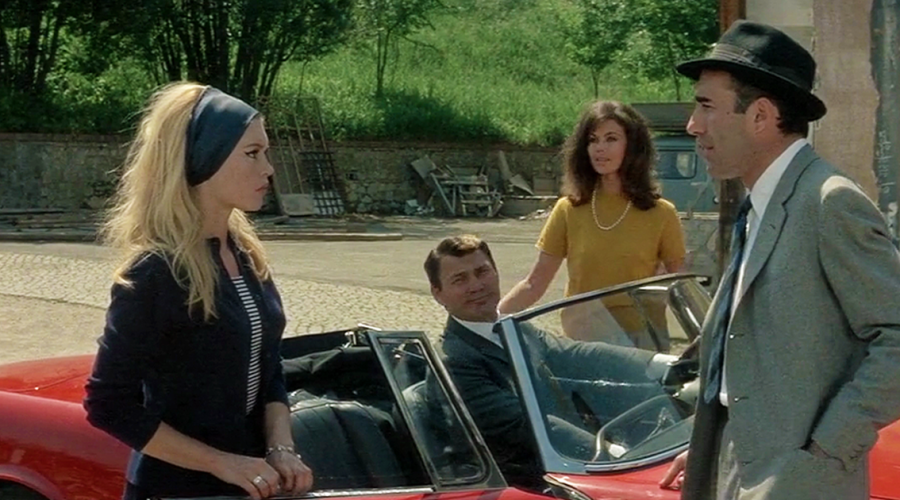

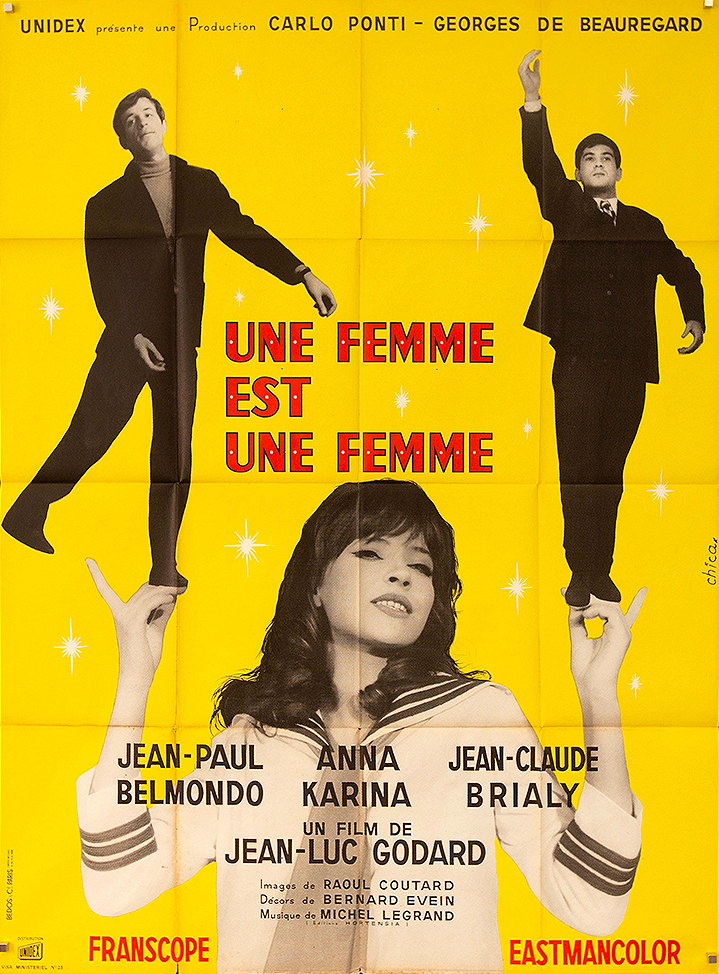

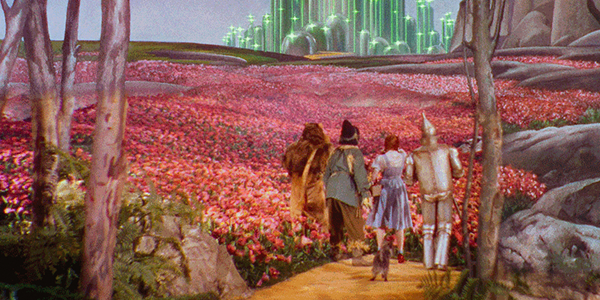

Godard again. If A Woman Is a Woman is the most accessible of his films, Contempt (Le Mépris) is the most mainstream, with a CinemaScope presentation, exotic locations, and a cast featuring Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance. Where Woman Is a Woman takes a decidedly oblique look at the Hollywood musical, here Godard directs his loving, withering gaze at the Hollywood epic.

Of course the whole exercise is droll, with the “epic” scenes staged with what would clearly be the catering budget for a Hollywood production. The main characters in the film within the film of The Odyssey are literally a bunch of statues, with the whole shot in extreme widescreen, which Fritz Lang famously quips “wasn’t made for man—it was made for snakes and funerals.”

But all of Godard’s films have that kind of sardonic carapace, and you’re likely to feel little more than annoyed or mildly amused if you don’t take up the challenge of trying to pierce their protective shell. For all its trappings of a travesty epic, Contempt—as Godard states explicitly during the opening credits—is a meditation on how the movies frame and channel our desires. The pivot for this is all the many shots of Bardot nude, which range from pinup to the bedroom intimacy of a couple in love.

But staying at that level would be love on Hollywood’s terms. Godard for the most part either eschews or exaggerates most of the traditional gestures used to express desire in movies, for instance brilliantly taking our dependence on the soundtrack to tell us what to feel and pumping George Delerue’s music cues so far past 11 that it feels like the film’s on the brink of a core meltdown. The music here isn’t used to just Mickey Mouse or accompany the action but is compensatory, both a parallel commentary and a force of nature. The lead characters are too cool with their emotions, too distanced from them to realize how deeply, almost inexorably, those surging undercurrents are guiding their actions—but the score makes it clear they’re playing with fire.

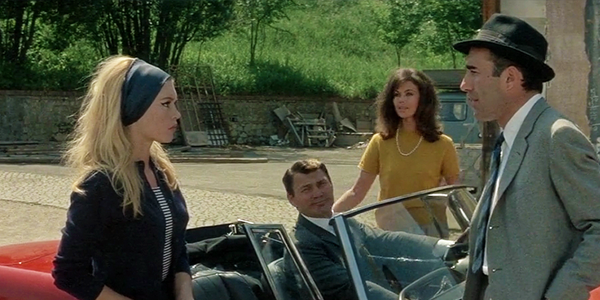

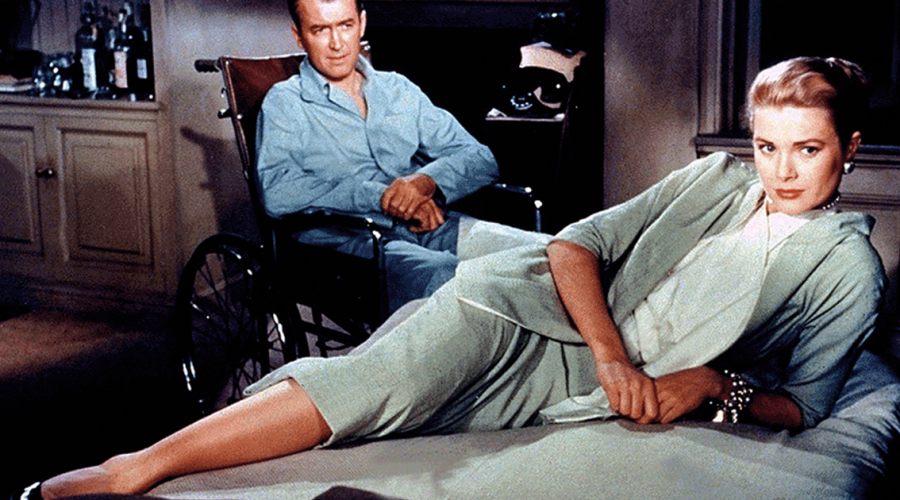

The masterstroke, though, is Godard turning widescreen on its head, most effectively deployed in the virtuoso half-hour-long scene in Bardot and Michel Piccoli’s unfinished apartment where we watch their marriage implode in real-time, shown in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio that transforms their domestic space into a battlefield and makes their feints and jabs, regroupings, and head-on assaults the offensives of massed armies. Godard here journeys back to the roots of Homer, using the movie spectacle as his sleek but insubstantial modern vessel.

The point of the above is that there’s plenty of meat here—so much that the film reveals some satisfying new level on every viewing—but that doesn’t mean it’s all prepared and presented with equal flair. The most egregious fumble is Palance, who often feels robotic, and who Godard encourages to behave like the worst kind of caricature of the ugly American. Godard’s disdain is so fierce it blinds him, resulting in a performance so predictable and one-dimensional it ultimately defangs some of his most telling points.

If A Woman Is a Woman is an evocative and indispensable record of Paris in the very early ‘60s, Contempt is an equally valuable document of the last, intense upwelling of modernism before it was devoured by the postmodernist beast, of the offshoot style that began to emerge in the mid ‘50s and was just beginning to get its bearings and bear its richest fruit when it was cut down and purged by the conformist, lowest-common-denominator impulses of mass culture, the army of the children of the machine.

But while the current online manifestation of A Woman Is a Woman is satisfying enough for now, the version of Contempt on Amazon Prime (which I would imagine is the same that’s on Google Play and elsewhere) can be maddening, offering tantalizing glimpses of how the film originally appeared but ultimately feeling like a faded family photo from the era. Studio Canal created a 4K intermediate for a theatrical release a few years ago, which could be a good thing or a bad thing, but hopefully we’ll get a chance to glimpse it soon enough.

Be warned that the sound is pretty awful, but it’s apparently just being true to the source tracks. Delerue’s music is distorted throughout, as is much of the dialogue track, and the quality of the dialogue recordings is all over the place, especially in the projection-room scene. But I wouldn’t want it any other way. Better a movie that bears traces of its origins than one that feels artificially pure, the product of endless lines of code.

One, kind of pointless, regret, though—because not much can be done about it—is that the original mix was mono. That seems like a lost opportunity, especially given all the widescreen blocking in Bardot and Piccoli’s apartment, where it seems like stereo could have been used to play off all the different presentations and meanings of distance.

Contempt is ultimately about how Hollywood romanticizes everything, even when it’s being sadistically cruel, and the dismal odds of anything resembling real emotion being heard above all the style- and genre-driven din. Nobody would ever use the words “gregarious,” “ebullient,” or even “warm” to describe Godard. There is something fundamentally cold about both him and his work. But you can sense him, in his early films at least, constantly trying to fend off the deadening chill of alienation, using abstraction, of all things, to keep his films fundamentally and intensely human.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Watching Contempt on Prime can be maddening, offering tantalizing glimpses of how the film originally appeared but ultimately feeling like a faded family photo from the era

SOUND | Be warned that the mono sound is pretty awful but it’s apparently just being true to the source tracks

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO ENLARGE

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC